Caldwell, Kansas, known as the Border Queen, saw wild days as a Kansas cowtown and a jumping-off point to the Oklahoma Land Rush days.

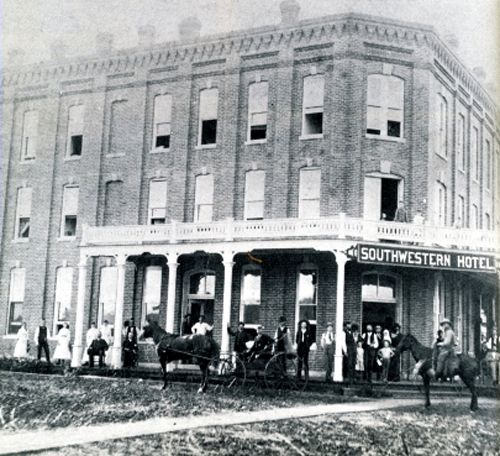

Located just north of the Oklahoma border, the town was established in 1871 and named in honor of United States Senator Alexander T. Caldwell of Leavenworth, Kansas. The first building was erected by Captain C. H. Stone, one of the founders of the townsite, who built a log house that was used as a store and the first post office. Stone became the fledgling city’s first postmaster. Other buildings soon followed, including a hotel, other businesses, and the Red Light Saloon, which thrived with Indian and cowboy customers.

Situated along the Chisholm Trail, the town catered to the many cowboys who passed by with their large cattle herds on their way to Abilene and Wichita. However, it remained little more than a trading post until 1879, when it had about 260 residents.

When the Santa Fe Railroad extended its line to Caldwell, Wichita investors noticed and formed a town company in 1879, selling lots for $125. The city was incorporated and quickly promoted its opportunity as a cattle shipping point. The town grew quickly and soon boasted some 1,500 people.

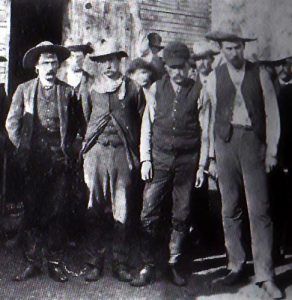

As the cowboys began to drive the cattle up the Chisholm Trail to Caldwell, the town took on all the elements of a lawless frontier settlement. These many drovers named the town the “Border Queen.”

As the town sprouted saloons, gambling dens, and brothels, the first town north of Indian Territory provided a place where the cowboys could go wild after months on the dusty and treacherous trail. Gunfights, showdowns, general hell-raising, and hangings soon became commonplace.

During its reckless cowtown period between 1879 and 1885, Caldwell “boasted” a higher murder rate and loss of more law enforcement officers than other, more famous cowtowns. During this period, violence claimed the lives of 18 city marshals, leading a Wichita editor to write, “As we go to press, hell is again in session in Caldwell.”

One of the first incidents occurred at the Moreland Saloon on July 7, 1879, when Deputy Constable James Wilson and a citizen, George Flatt, cornered two cowboys named Woods and Adams, who had been firing their guns outside the saloon in celebration of being paid for a Texas cattle drive earlier in the day. The confrontation led to gunplay, and Woods and Adams were dead when the smoke cleared. In the melee, an innocent bystander named Kiser was wounded. Having made a reputation for himself, Flatt soon became Caldwell’s first City Marshal. He gladly took credit for shooting the cowboys, but no one ever came forward to accept responsibility for wounding Mr. Kiser.

However, Flatt was not well-liked by local citizens, and on April 5, 1880, a new mayor was elected in Caldwell, namely Mike Meagher. One of the first things Meagher did was discharge City Marshal George Flatt because he disapproved of Flatt’s confrontational way of law enforcement.

He then appointed William Horseman as the new marshal, Frank Hunt and Dan Jones as deputies, and James Johnson stayed as constable. Flatt was none too happy about this event and wasted no time voicing his complaints about town.

On the evening of June 18, 1880, a drunken Flatt made his rounds in several Caldwell saloons, voicing his complaints to anyone who would listen. Somewhere along the line, he ran into Frank Hunt, and the two argued until Hunt finally persuaded Flatt to go home at about 1:00 a.m. But Flatt wouldn’t make it. On his way, he was ambushed and died in the street with a bullet in the back of his skull.

Mayor Mike Meagher and police officers William Horseman, Frank Hunt, James Johnson, and Dan Jones were soon arrested by Sumner County Sheriff Joe Thralls for the murder. Although all of the men were bound over for trial, only William Horseman was tried. A year later, he was acquitted.

But for Mike Meagher, he would get his due on December 17, 1881, in a shootout with Jim Talbot and three other men. Meagher was killed. Also killed by the gunfire was George Spears, a former policeman who had changed to the Talbot side. The gunfight lasted long enough for a hardware store to pass guns and ammunition to townspeople. Only one of Talbot’s men was ever convicted of the murder. After his release, Talbot was acquitted but was later killed, probably by Mike’s brother, John, who was seen following Talbot from the courthouse.

Caldwell needed its ninth marshal by the time it was three years old. Unfortunately for the City and the new marshal, a 10th would soon follow. Appointed in March 1882, George S. Brown, 28, lived to enforce the law only until the summer. On June 22, 1882, Marshal Brown was killed by cowboys Steve and Jess Green in the Red Light Saloon as Brown and a deputy answered a disturbance call. With the help of the saloon employees, the Green brothers escaped into Indian Territory, only to be caught in a gunfight with Territory lawmen in October. Steve Green and a deputy sheriff were killed, and Jess Green was captured, riddled with 13 gunshot wounds. The Kansas governor gladly paid the Texas posse the $1,000 in Kansas reward money. Jess Green died in the county jail prior to his murder trial.

Also hired in 1882 was another Mr. Brown – one Henry Newton Brown, as Assistant Marshal. He was later promoted to City Marshal.

But, Brown had failed to tell the city council about his interesting past, which included cattle rustling, riding with Billy the Kid, and a trivial murder charge during the Lincoln County War in New Mexico.

Brown hired his friend, Ben Wheeler, aka Ben Robertson, and the two men “cleaned up” the tough town quickly. When Brown felled two outlaws in the streets of Caldwell in 1883, the Caldwell Post bragged that Brown was “one of the quickest men on the trigger in the Southwest.” So taken were the town citizens that they presented him with a new, engraved Winchester rifle.

What the town didn’t know, however, was that Brown had gotten into financial trouble and returned to his outlaw ways. On April 30, 1884, Brown, his deputy, Ben Wheeler, and two other former outlaw friends attempted to rob a bank in Medicine Lodge, Kansas. Though they made off without money, they shot and killed two bank employees. A posse was immediately after the would-be robbers, catching up with them right out of town.

They were taken to the Medicine Lodge jail, and a mob outside formed in no time, chanting, “Hang them! Hang them!” At about 9:00 p.m. that night, the mob broke into the jail, and the prisoners attempted to dash for freedom. Brown fell quickly, his body riddled with bullets. Wheeler was also wounded but was dragged along with the other two to a nearby elm tree and hanged.

Later that year, when “Buffalo Bill” Brooks, a former Newton and Dodge City lawman, turned to outlawry, he was captured by a posse with several other horse thieves near Caldwell. Hauled to jail to await trial, a lynch mob stormed the Caldwell on July 29 and lynched Brooks and two other horse thieves by L.B. Hasbrouck and Charlie Smith.

By the following year, the cattle trade had moved farther west, and Caldwell settled into an agricultural community. Over a million longhorns and their guardian cowboys traveled through Caldwell during its thriving cattle days.

A life-sized silhouette of a trail cattle drive sits on a hill outside Caldwell, Kansas, Kathy Weiser,

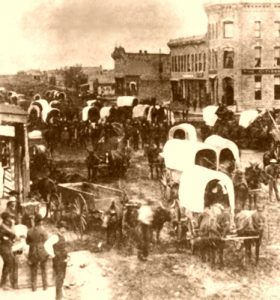

Caldwell saw more wild days in 1893 when Congress opened the Cherokee outlet to the south for settlement. Soon, Caldwell was filled with thousands of land-hungry pioneers preparing for America’s last great land rush. On September 16, 1893, 15,000 people gathered in Caldwell, awaiting the cavalry soldiers’ gunshots to start the mad rush for land.

Afterward, Caldwell continued to prosper until other towns were established in the new territory to supply the settlers’ needs. The town survived as a railroad junction and agricultural community. Today, it supports a population of about 1,300.

Though Caldwell’s days of hustle and bustle are gone, the small city displays its rich heritage through several historical markers that dot the town, at the Cherokee Strip Visitors Center & Museum at 1 North Main, its Boot Hill cemetery, and several celebrations throughout the year.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See:

Kansas Cowtowns – Lawlessness on the Prairie