By Hiram Martin Chittenden, 1902

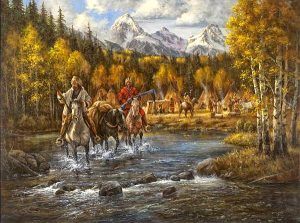

Pierre’s Hole, as it was then called, or Teton Basin, its present name, is one of those valleys which are a veritable oasis in the desert of rugged mountains. Very few of these valleys exceed that of Pierre’s Hole in beauty. It is located in Idaho and is overhung on the east by the Grand Tetons in Wyoming. The valley extends in a direction from southeast to northwest. It is 30 miles long and from 5 to 15 miles wide. It appears like a broad, flat prairie almost destitute of trees except along its principal river and the various tributaries.

In the summer of 1832, the Rocky Mountain and American Fur Companies had their rendezvous in the upper part of the valley of Pierre’s Hole, some 12 to 15 miles from Teton Pass. With their accustomed alacrity of movement, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company managers had excelled over their rivals in reaching the rendezvous with their annual supplies. William L. Sublette arrived with a party of about 60 men on July 6. Nathaniel Wyeth was with him, and so were the remnants of Jefferson Blackwell’s and John Gannt’s parties of the previous year whom Sublette had found on the Laramie River. William Vanderburgh and Andrew Drips of the American Fur Company were also present. Lucien Fontenelle, who was coming from Fort Union, North Dakota, with supplies, was still far behind in the Bighorn Valley. Captain Benjamin Bonneville, likewise headed in the same direction, was still in the valley of the Platte River.

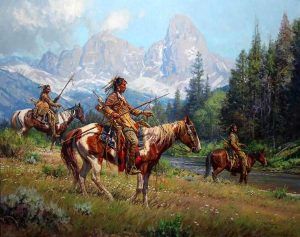

In the valley of Pierre’s Hole were also hundreds of Indians, mainly of the Salish and Nez Percé tribes. The Gros Ventre, ever hostile to the whites, were this year particularly troublesome around the headwaters of the Snake and Green Rivers. Although a post had been built in the Blackfeet country scarcely a year before — Fort Piegan, Montana, at the mouth of the Marias River — this fact seems not at all to have tempered the ferocity of the tribe. They were returning home from a visit to their kindred, the Arapaho. Sublette had had a sharp brush with them on the way to the rendezvous, and Thomas Fitzpatrick, who had gone on ahead, was unhorsed and forced to hide in the mountains and wandered for five days without food, reaching the rendezvous more dead than alive.

When the rendezvous business was nearly completed, a party of trappers under Milton G. Sublette set out on July 17 in the direction of the main Snake River toward the southeast. Nathaniel Wyeth embraced this opportunity to secure a good escort out of the Blackfeet country for the remnant of his party who had decided to continue to the Pacific Coast. The joint party proceeded just a short distance, six or eight miles, and encamped for the night. Just as they set out the next morning, they discovered a party of horsemen approaching. They were in doubt for a time whether it was white or Indian, but they soon found it was a band of Gros Ventre. They were approaching in two parties and numbered about 150 men. According to Zenus Leonard, they carried a British flag they had captured from a party of Hudson’s Bay Company trappers, whom they had recently defeated. The Indians came down into the valley with such fierceness that the trappers could not, at first, tell whether they were buffalo, white men, or Indians. Finally, by the aid of Wyeth’s looking glass, they discovered that there were also Blackfeet Indians, and Milton Sublette at once sent two men to the rendezvous for assistance.

In the meantime, a tragedy of revenge had been enacted on the plain. The Blackfeet, discovering that the force before them was larger than they had supposed, made signs of peace, displaying, it is said, a white flag.

But, such was their general reputation for disloyalty that no confidence was placed in their friendly advances. There were, moreover, in the white camp two men who cherished inextinguishable hatred toward the Blackfeet. One of these was Antoine Godin, whose father had been murdered by these Indians on Godin Creek. The other was a Salish chief whose nation had suffered untold wrongs from the tribe. When these two men advanced to meet the overtures of peace, a Blackfeet chief came to meet them. By a previous arrangement between Godin and the Salish chief, the latter shot the Blackfeet dead the instant Godin grasped his hand in friendship. Seizing the chief’s scarlet robe, Godin and his companion beat a hasty, though safe, retreat.

The Indians withdrew into some timber nearby, surrounded by a thicket of willows. They immediately entrenched themselves by digging holes in the ground and building a breastwork of timber in front of their rifle pits. The women mostly did this work, the Indians maintaining a skirmish line in front of the fort. While some of the men had gone to the rendezvous for reinforcements, Milton Sublette’s trappers held the Indians within the woods, and Wyeth fortified his camp, where he ordered his men to remain.

Upon receiving the news of the attack, William Sublette and Robert Campbell immediately left the rendezvous and, in short order, arrived on the field with a large force of whites and their Indian allies.

Sublette assumed the direction of the battle. He forbade Wyeth’s men and his raw recruits to engage in the fight and used only the seasoned trappers and the Indians. However, Wyeth was present in the engagement part of the time. When they saw the overwhelming force with which they had to reckon, the Blackfeet withdrew within their entrenchments.

The whites and allied Indians commenced the attack by randomly firing into the thicket. This accomplished nothing but allowed the Blackfeet to do some practical work in return. It was apparent that other measures would have to be adopted to dislodge them, and William Sublette proposed to storm the breastworks.

His men thought it too dangerous, but Sublette insisted. About 30 whites and many Indians joined him and entered the willow thickets together. Pushing their way cautiously through the tangled shrubs, Sublette, Campbell, and Alexander Sinclair of Arkansas led the others toward the Indian “fort.” Sublette and Campbell and doubtless others had made their wills to each other in anticipation of the consequences that might ensue. After working their way on hands and knees through the dense line of willows, they came to the more open ground and saw the rude fortification of the Indians. As they emerged into this open space, they were more exposed to the fire of the Blackfeet. Sinclair was killed on the spot, and Sublette was severely wounded. In the meantime, Wyeth, with some Indians, had gained nearly the opposite side of the fort, and one Indian near him was killed by a chance shot from Sublette’s party. The besieged Indians suffered little at this time, for they were well protected, although completely overmatched in numbers.

The attack continued for the greater part of the day without any substantial progress, owing to the secure position of the enemy and the evident reluctance of the attackers to storm it. Finally, Sublette decided to burn them out, although much against the wishes of the friendly Indians, who wanted to plunder the fort. A train of wood was laid and was about to be ignited when an incident occurred, which brought immediate relief to the beleaguered garrison. One of the friendly Indians, who understood the Blackfeet language, held some conversation with the besieged during the fight. They now told him that they knew that the whites could kill them but that they had 600-800 warriors who would soon arrive and who would give them all the fighting they wanted. In the process of interpretation, the Blackfeet was made to say that this force was attacking the main rendezvous. Such an attack would have been disastrous without the fighting force, and the whites quickly hurried off to the rendezvous site without waiting to verify the news. Before the mistake was discovered, it was too late to resume the attack. On the following morning, the Blackfeet fort was found abandoned. The casualties in this fight were, on the side of the whites, five were killed, including Alexander Sinclair, and six were wounded, of whom William Sublette was one. The allied Indians lost seven killed and six wounded. The loss of the Blackfeet was never fully known. They left nine dead warriors in the fort together with 25 horses and nearly all their baggage. Later, it was said that the Blackfeet admitted to having lost 26 warriors.

The Battle of Pierre’s Hole was not without its important sequels. On July 25, seven men of Wyeth’s party, Alfred K. Stephens and four men, the joint party, including a Mr. More of Boston, a Mr. Foy of Mississippi, and two grandsons of Daniel Boone, set out from the rendezvous to return East. They had intended to accompany William Sublette, but his wound postponed the latter’s departure about ten days. Impatient of the delay, these men set out eastward and, on the following day, were attacked in Jackson’s Hole in Wyoming by a band of some 20 Blackfeet. More and Foy were killed, and Stephens was wounded. With the rest of the party, he returned to the rendezvous, where he lingered until July 30, when he died just after starting for St. Louis, Missouri, in company with William Sublette. His horses and traps were sold the same day, and his beaver fur was taken to St. Louis. With his party of about 60 men and the furs they had collected over the past year, Sublette left the rendezvous on July 30. The day after crossing the Snake River, on August 4, they passed the large band of Blackfeet whom the Indian had told them at the Battle of Pierre. These Indians had been hovering in the vicinity of Lucien Fontenelle and Benjamin Bonneville camps but had not ventured to attack. In like manner, their recent experience in Pierre’s Hole made them hesitate about attacking Sublette’s party, and he suffered to pass unmolested. This band of Indians finally left the country by way of the Wind River Valley, where they were attacked and routed by some Crow Indians with a loss of 40 killed. The remainder were scattered like fugitives throughout the Crow country.

It will be remembered that Antoine Godin killed the Blackfeet chief at Pierre’s Hole in revenge for his father’s death. But the account was not yet considered closed — at least on the part of the Blackfeet. Between September 1834 and September 1835, the exact date unknown, a party of Blackfeet appeared on the opposite bank of the Snake River from Fort Hall, Idaho. They were led by a desperado named James Bird, a former employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who, having been made a prisoner by the Blackfeet in a skirmish with some of that tribe, had remained with them and had become an influential chieftain. From the opposite side of the Snake River, Bird requested Godin to come across and buy their furs. Godin complied, not suspecting treachery. He sat down to smoke with the company when Bird signaled to some Indians, who shot him in the back. While he was yet alive, Bird tore his scalp off and cut the letters ” N.J.W.,” Wyeth’s initials, on his forehead. Thus ended the tragedy of Pierre’s Hole.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

About the Author: The Battle of Pierre’s Hole was written by Hiram Martin Chittenden and included in his book, The American Fur trade of the Far West, published in 1902. Chittenden served in the Corps of Engineers, eventually reaching the rank of Brigadier General. He was in charge of many notable projects, including work at the Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks and the Lake Washington Canal Project. He was also an author, penning historical volumes, tour guides, and poetry. As it appears here, the story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader.

Also See: