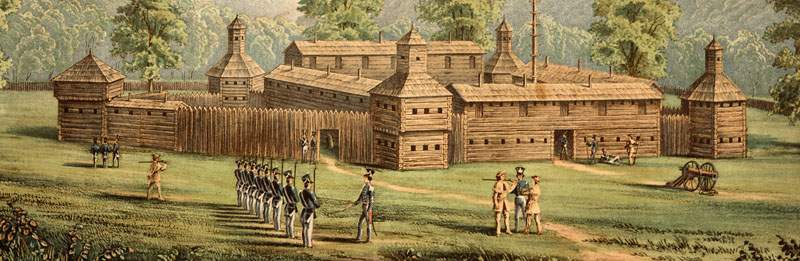

Fort Washington, in present-day Cincinnati, Ohio, was a fortified stockade with blockhouses built by order of General Josiah Harmar. Major John Doughy established the fort on the Ohio River’s north bank at the mouth of the Licking River in 1790 to protect settlers in the old Northwest Territory. It was named after President George Washington.

After the American Revolution, many settlers came down the Ohio River into the old Northwest Territory, looking for land and new opportunities.

Land speculators began buying 640-acre chunks of land and breaking those into smaller tracts that more people could afford. Surveyors began risking their lives surveying these lands, which could be legally divided with a deed. New Jersey Supreme Court Justice John Symmes was one of those who bought and sold land in Ohio. It appeared to him that this venture would be profitable if the constant threat of Indian attacks were removed. The more land that was sold, the more violence and killings increased.

A series of events culminating in the fort’s construction began in Trenton, New Jersey. On November 26, 1787, Judge John Cleves Symmes issued a pamphlet advertising the rich lands between the two Miami Rivers in the Ohio country, which he and his partners had for sale. The speculators quickly sold two large tracts of land along the Ohio River to outside interests.

One group led by Benjamin Stites, an early explorer of the region, established Columbia, about one mile due west of the Little Miami River on November 18, 1788. Just over a month later, 22 settlers led by Mathias Denman and Colonel John Patterson landed at the foot of present-day Sycamore Street in Cincinnati. On December 28, 1788, they established the settlement of Losantiville (later Cincinnati.)

Judge Symmes was not content with speculating idly about the territory’s future. The former Continental congressman and justice turned pioneer in January 1789, when he and 60 settlers established the settlement of North Bend on the Great Miami River.

At this time, Josiah Harmar, who was in command of the First American Regiment garrisoned at Fort Harmar, decided to move his headquarters further down the Ohio River to a point where a stronger military presence was needed.

The future of these three tiny settlements, and most of the old Northwest Territory, was still in doubt in 1789. The treaties signed by Native Americans at Fort Stanwix, New York, in 1784, Fort McIntosh, Pennsylvania, in 1785, and Fort Finney, Ohio, in 1786 technically opened southern Ohio to white settlement. However, the Indians who had signed these agreements had been bribed or had been intimidated into doing so, and many of the signees were minor chiefs who had no real tribal authority. At Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois Tribe ceded land belonging not to the Six Nations but rather to the Shawnee. The tribes in the region did not intend to relinquish their lands so easily.

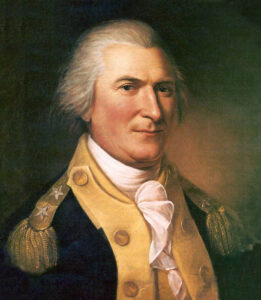

General Arthur St. Clair was appointed governor of the old Northwest Territory by a vote of Congress on October 5, 1787. When he arrived in Cincinnati, the settlement consisted of two small log houses and several cabins.

National leaders representing the Haudenosaunee, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Sauk, Wyandot, and Lenape met with treaty negotiators from the United States, including Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, Josiah Harmar, and Richard Butler In January 1789. The Treaty of Fort Harmar was concluded at Fort Harmar on January 9, 1789, with these tribes who had territorial claims within the European land claim acquired in 1783 by the United States from Great Britain, known as the Northwest Territory. The treaty allowed the government the right to allow settlers to start making legal claims north of the Ohio River. However, not all the Native Americans had signed the Harmar Treaty. It was signed by some Native Americans who may or may not have understood the terms of that agreement. Some, particularly the Shawnee, understood exactly what the treaty meant, and they refused to negotiate, much less sign the documents the government was presenting.

Indians had long protested the presence of American settlers moving onto the land north of the Ohio River. Many had sided with the British during the American Revolution, hoping this alliance would fend off the advancing Americans. During that war, a military expedition led by George Rogers Clark moved up from what is now Cincinnati and destroyed a Shawnee village near present-day Piqua. These attacks left deep scars that would haunt the Shawnee until after the end of the War of 1812, which took their leader, Chief Tecumseh.

Because of the Indian threat, the three small settlements had blockhouses for protection by the spring of 1789. At Columbia, Stites built and garrisoned his own small fort. Losantiville relied on a blockhouse built by George Rogers Clark in 1780. Judge Symmes’ hamlet at North Bend was initially protected by a blockhouse garrisoned by Ensign Francis Luce and 18 regulars. The latter was soon reduced by fevers, two desertions, and one death, leaving a total of only 12 men. Symmes had made arrangements in advance for army protection, but Luce’s negligible detachment was not what he had in mind.

After several requests to Philadelphia, Symmes finally received the protection he requested. On August 9, 1789, brevet Brigadier General Josiah Harmar dispatched a full company under Captain David Strong from Fort Harmar at Marietta, Ohio, to North Bend. Harmar’s second-in-command, Major John Doughty, followed the company two days later. Doughty, who had constructed Fort Harmar in 1785, was sent “to select the site of a fort intended to protect the settlement on the Symmes Purchase.”

Doughty arrived on August 16, and by August 21, he had dispatched a report back upriver to Harmar. The major stated that he had spent three days reconfiguring the region between the two Miami Rivers. He carefully weighed the advantages of various locations, such as safety from flood, a fresh supply of water, and a healthy environment for the garrison. He finally chose a spot “opposite the Licking River, high and healthy, abounding in never failing springs.”

Doughty’s site for the fort was about 550 feet from the Ohio River. The forest surrounding the site comprised maple, ash, walnut, oak, sycamore, poplar, and hickory trees, thus providing Doughty with onsite building materials. It was also a strategic location, only seven miles from Columbia and 15 miles from North Bend.

Doughty designed the fort, but its future quartermaster, Lieutenant John Pratt, and newly arrived Captain William Ferguson supervised the construction. First, the site was cleared of all underbrush, and every tree was cut down for several hundred yards. Next, the five-sided two-story blockhouses were erected with the upper story projecting over the lower. Square in shape and about 20 feet wide on each side, the blockhouses were built of heavy hewn logs. Scaling the walls was next to impossible with cannon or small arms fire. In addition, musket holes were cut into the floor for firing downward.

The barracks and storehouses formed the curtain’s middle wall, with the open spaces covered by a log palisade typical for outposts throughout the region. The palisade logs were about 20 feet long and placed upright in a four-foot deep trench, forming a 16-foot high wall around the fort. Two ravelins (triangular fortifications) were built on the west and north sides of the 200-foot square stockade. The south barracks, containing the main gate, were divided into six rooms. There was a flagstaff in the center yard and at least one well. A white picket fence enclosed the entire 15-acre military reservation. Fort Washington was distinguished by its large size: it was larger than a modern city block and designed to house up to 1500 men. General Josiah Harmar described it as “one of the most solid substantial wooden fortresses… of any in the Western Territory.”

General Harmar officially took command of the still unfinished fort and 300-man garrison on December 29, 1789. Among the contingent was military surgeon Dr. Richard Allison. He was the only doctor for the fort, 11 families, and 22 single men in Losantiville. At that time, the population of the crude village, exclusive of the military, probably did not exceed 150. Three days after General Harmar took up his quarters at Fort Washington, on January 1, 1790, Governor St. Clair was received with due ceremony by the troops and citizens of Losantiville. Though he stayed for only three days, his visit was more than a routine courtesy call. The steady westward advance of settlement had left his present headquarters at Fort Harmar too far east to govern the vast Northwest Territory effectively.

Starting at Fort Pitt, a line of fortifications had crept westward, cutting off the Ohio River to hostile tribes and helping to secure Kentucky and western Pennsylvania. Each new stockade, Fort McIntosh, Fort Henry, and Fort Harmar, was a step farther into Indian country. The tenuous line was completed with Fort Nelson at Louisville securing the Falls of the Ohio River. St. Clair and Harmar both wanted to go deeper into the wilderness to destroy the hostile, threatening villages and burn the Indians’ crops. To accomplish this, they envisioned a new line of forts extending north toward the Indians’ power bases along the Wabash and Maumee Rivers. Fort Washington, the territory’s most significant, newest, and most powerful fort, became St. Clair’s capitol and the center from which this new line of forts would grow. From its southeastern blockhouse, Arthur St. Clair transacted his official duties as governor of the Northwest Territory.

The tall Scottish-born St. Clair was quite pleased with the fort and agreed with Harmar that Fort Washington was an appropriate name. The name of the town was another matter. St. Clair had found the name Losantiville, a jumble of French and Latin meaning “Town opposite the Licking River,” far too distasteful for any capital of his. On January 4, 1790, he officially rechristened the town Cincinnati in honor of the Society of the Cincinnati, of which he was a member.

The Shawnee, Miami, and Lenape Indians had their own plans. They launched a series of reprisal raids in the spring of 1790 to drive the latest intruders off their lands. Kenton’s Station, a small post up the Ohio River, was attacked, and more than a dozen settlers were killed. Shawnee Indians attacked and plundered a small convoy of riverboats on the Great Miami River. On more than one occasion, hostiles stole horses tethered to Fort Washington’s gates. The fort itself, however, was never in any real danger of attack; its cannon and the Indians’ lack of patience for a prolonged siege ruled out any attack. Instead, the fort became the staging ground for three major campaigns against the hostile tribes. Two of these campaigns, however, ended in disaster.

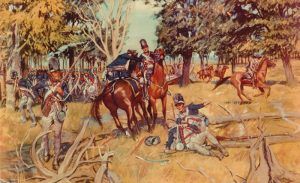

On October 21, 1790, General Josiah Harmar led more than 600 men into an ambush near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana, in which he lost more than 182 men.

In 1791, a triangular extension was added to the fort’s western side, with a fifth blockhouse at its tip. The new section contained the craftsmen’s yard with its blacksmiths, armorers, carpenters, and wheelwright’s shops. A sixth and final extension was added late in 1791 to the northern side built to house the wounded from Harmar’s disastrous campaign. It became Cincinnati’s first hospital.

In early October 1791, General Arthur St. Clair led another expedition out of Fort Washington while continuing as governor. More than 3,000 men followed him into the wilderness, but because of disease, desertions, and St. Clair’s penchant for building forts, his force soon was reduced to about 1,500 regulars and militia. During the early morning hours of November 4, 1791, the governor’s makeshift camp was surprised by thousands of warriors. St. Clair’s Defeat was the worst ever suffered by American forces at the hands of Native Americans. St. Clair lost 37 officers and 593 men, the survivors straggling back in panic to Fort Washington.

However, the last major campaign that originated from the fort was victorious. Washington finally had found a competent Indian fighter in Major General “Mad Anthony” Wayne. He took command of the fort in early 1793, and by winter, he was ready to lead his forces against the enemy. After months of successful campaigning, he defeated the combined tribes on August 20, 1794, at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. This victory led to the Treaty of Greeneville, effectively ending Indian resistance in the Ohio country.

Though this treaty ended the fort’s days as an important campaign staging area, it remained an important administrative center and contained a large garrison for several years. However, there was little to do, and drunkenness was a problem, as well as gambling, which tended to lead to fights. Neither Cincinnati nor Fort Washington appealed much to General Wayne, who complained that the town was dirty and that his attempts at instilling discipline into his men were being undermined constantly by “wenches” who were selling whiskey to his soldiers.

Aside from drinking, there was little else to do for amusement. There was little to read, and the men far outnumbered the women in the area. Though hunting and fishing in the area were excellent, there was scarce ammunition.

In the spring of 1793, Major General Anthony Wayne moved his forces from the training center at Legionville, Pennsylvania, down the Ohio River by barge to a camp outside Fort Washington called Hobson’s Choice. In the fall, Wayne departed Fort Washington and moved his army northward, past Fort Jefferson, to build Fort Greene Ville.

Though Fort Washington was designed to house more than 1,500 men, by 1802, it contained only half a company, about 35 men, and it had fallen into disuse and disrepair. It was too far east to be an effective military or administrative post, and Cincinnati had become a boom town and needed to expand.

In 1803, Fort Washington was replaced by the more extensive Newport Barracks established to house the Kentucky Militia. It was opened just across the Ohio River in Newport, Kentucky. On February 28, 1806, Fort Washington was abandoned, surveyed, and laid off into lots sold to the highest bidders at a sale at the Cincinnati Land Office. Within a few years, no visible trace of this once mighty and important outpost remained, except the now flourishing town of Cincinnati.

Fort Washington was one of the more critical frontier fortifications of its day. From 1789 to 1804, it served as “the Pentagon, the capitol, and the White House of the West.”

In October 1952, excavators discovered the remnants of Fort Washington’s gunpowder magazine under the northeast corner of Broadway and Third Streets at the site where Western & Southern Life Insurance Company’s parking garage was to be constructed.

Researchers with the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio first visited the site on October 13, 1952. Fort Washington Way, a section of Interstate 71 and U.S. Route 50 that runs through downtown Cincinnati and passes just in front of the former fort, retains the fort’s name. The location is marked by a plaque at the Guilford School building, at 421 E 4th St, Cincinnati, which now occupies the site.

Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2024.