By David Saville Muzzey, 1920

From the death of Christopher Columbus in 1506 to the planting of the first permanent English colony on the shores of America in 1607, just a century elapsed, — a century filled with romantic voyages and thrilling tales of exploration and conquest in the New World. Centuries later, men explored new countries for the scientific study of the native races or the soil and its products, or to open up new markets for trade and develop the hidden resources of the land; but in the romantic 16th-century Spanish noblemen tramped through the swamps and tangles of Florida to find the fountain of perpetual youth, or toiled a thousand miles over the western desert, lured by the dazzling gold of fabled cities of splendor. The 16th century was also a century of intense religious beliefs, so a grim spirit of missionary zeal mingled with the thirst for gold. The cross was planted in the wilderness, and the soldiers knelt in thanksgiving on the ground stained by the blood of their heretical neighbors.

But, it was Asia with its fabulous wealth, which was the real goal of European explorers. America was an obstacle. Even far into the 17th-century, the mariners were searching the northern coast of America for a way around the continent and hailing the broad mouth of each new river as a possible passage to the Indies.

Christopher Columbus, in his fourth voyage in 1502, skirted the coast of Central America, in hopes of finding a passage to Cathay (China), while Italian explorer, Amerigo Vespucci, in his great voyage of 1501-1502, followed the South American coast far enough to demonstrate that he had found a “new world,” even if he had not discovered a gateway to the East.

A third mariner was also diligently searching for a way to the Indies — Ferdinand Magellan. A Portuguese explorer in the service of Spain, Magellan, along with five ships and about 300 men, started on what proved to be perhaps the most romantic voyage in history in September 1519.

Reaching the Brazilian coast, he made his way south. After quelling a dangerous mutiny in his winter quarters on the bleak coast of Patagonia, he entered the narrow straits (afterward called the Straits of Magellan) at the extremity of South America. A stormy passage of five weeks through the tortuous narrows brought the ships out on the calm waters of an ocean to which, in grateful relief, he gave the name “Pacific.”

But, Magellan was to meet worse trials than storms when he put out into the great ocean. Week after week, he sailed westward across the interminable sea, little dreaming that he had embarked on waters that cover nearly half the globe. Hunger grew to starvation, to thirst, to madness. Twice on the voyage of 10,000 miles, land appeared to the eyes of the famished sailors, only to prove a barren, rocky island. At last, the inhabited islands of Australia were reached. Magellan himself was killed in a fight with the natives of the Philippine Islands, but his sole seaworthy ship, the Victoria, continued westward across the Indian Ocean and, rounding the Cape of Good Hope, reached Lisbon, Spain with a crew of 18 “ghostlike men,” on September 6, 1522.

Magellan’s ship had circumnavigated the globe. His grand voyage proved conclusively that the earth was round and showed the great preponderance of water over land. It also demonstrated that America was not a group of islands off the Asiatic coast (as Columbus had thought), nor even a southern continent reaching down in a peninsula from the corner of China, but a continent set in its hemisphere, and separated on the west from the old world of Cathay, by a far greater expanse of water than on the East from the old world of Europe. It still required generations of explorers to develop the true size and shape of the western continent; but, Magellan’s voyage had located the continent at last in its relation to the known countries of the world.

While Magellan’s starving sailors were battling their way across the Pacific Ocean, stirring scenes were enacted in Mexico. Starting from Haiti as a base, the Spaniards had conquered and colonized Puerto Rico and Cuba in 1508 and sent expeditions west to the Isthmus of Panama in 1513 and north to Florida the same year. In 1519 Hernando Cortez, a Spanish adventurer of great courage and wisdom, was sent by the governor of Cuba to conquer and plunder the rich Indian kingdom that explorers had found to the north of the isthmus. This was the Aztec confederacy of Indian tribes under Emperor Montezuma. The land was rich in silver and gold; the people were skilled in art and architecture. They had an elaborate religion with splendid temples but practiced the cruel rite of human sacrifices. Their capital city of Mexico was situated on an island in the middle of a lake and approached by four causeways from the four cardinal points of the compass.

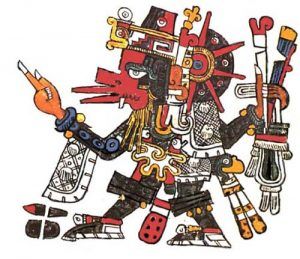

One of their religious legends told of a fair-haired god of the sky (Quetzalcoatl), who had been driven out to sea, but who would return to rule over them in peace and plenty. When the natives saw the Spaniard with his “white-winged towers” moving on the sea, they thought the “fair god” had returned. Cortez was not slow to follow up this advantage. His belching cannon and armored knights increased the superstitious awe of the natives. He seized their ruler, Montezuma, captured their capital city, Mexico, and made their ancient and opulent realm a dependency of Spain in 1521. It was the first sure footing of the Spaniards on the American continent and served as an important base for further exploration and conquest.

The twenty years following Cortez’s conquest of Mexico marked the height of Spanish exploration in America. From Kansas to Chile and from the Carolinas to the Pacific Ocean, the flag and speech of Spain were carried. No feature of excitement and romance is absent from the vivid accounts which the heroes of these expeditions have left us.

Now, it is a survivor of shipwreck — Cabeza de Vaca — in the Mexican Gulf, making his way from tribe to tribe across the vast stretches of Texas and Mexico to the Gulf of California; now it is the ruffian Captain Gonzalo Pizarro, repeating south of the isthmus the conquest of Cortez, and adding the untold wealth of the silver mines of Peru to the Spanish treasury; now it is the noble governor Hernando de Soto, with his train of 600 knights in “doublets and cassocks of silk” and his priests in splendid vestments, with his Portuguese in shining armor, his horses, hounds, and hogs, all ready for a triumphal procession to kingdoms of gold and ivory — but doomed to toil, with his famished and ambushed host, through tangle and swamp from Georgia to Arkansas, and finally to leave his fever-stricken body at the bottom of the Mississippi River; now it is Francisco Coronado and his 300 followers, intent on finding the seven fabled cities of Cibola, and chasing the golden mirage of the western desert from the Pacific coast of Mexico to the present state of Kansas.

Spanish Conquistadors

For all this vast expenditure of blood and treasure, not a Spanish settlement existed north of the Gulf of Mexico in the middle of the 16th-century. The Spaniards were gold seekers, not colonizers. They had found a few Indians living in cane houses and mud pueblos, but they had not found the fountain of perpetual youth and the cities of gold. They could not, of course, foresee the wealth which one day would be derived from the rich lands through which they had so painfully struggled, and the survivors returned to the Mexican towns discouraged and disillusioned.

However, South and west of the Gulf of Mexico, in the islands of the West Indies, the Spaniards had built up a huge empire. The discovery of gold in Haiti and the conquest of the rich treasures of Mexico and Peru brought thousands of adventurers and tens of thousands of African-American slaves to tropical America. Spain governed the American lands despotically. Commerce and justice were exclusively regulated through Seville’s “India House” and Spanish culture was introduced. In 1536, a printing press was set up, and shortly after the middle of the century, universities were opened in Mexico and Peru. The essential features of the Spanish government also were brought across the ocean — its absolutism in government and religion. Trade was restricted to certain ports; heretics and their descendants to the third generation were excluded from the colonies; the natives were almost exterminated by the rigors of the slave driver in the mines. The land was the property of the sovereign. He was granted to nobles, who, under the guise of protecting and converting the natives, made their fiefs great slave estates and treated both Indians and African-Americans with frightful severity.

Despite these evil features, however, Spanish colonization was a boon to the New World. The Spaniards introduced European cultivation methods into the rich islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, and Jamaica and opened precious veins of gold and silver in Mexico and Peru. They built cities, dredged and fortified harbors, founded schools and universities, erected cathedrals and palaces. Spain, welded into a nation by the union of the crowns of Aragon and Castile, her king elevated to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in the person of Charles V, was the most powerful state in Europe in the 16th Century. Gold from the American mines enhanced the splendor of her throne, and her civilization, in turn, was reflected in her colonies in the New World. The decline of Spain’s power began, however, with the wars which Charles’s despotic son Philip II waged to crush the liberty of his Dutch subjects and the repulse which his great Armada met at the hands of Queen Elizabeth’s seamen in 1588. When the sixteenth century closed, the vigor of Spanish colonization was gone.

The Spaniards were the chief, but not the only, explorers in America in the 16th-century. In 1524 the king of France sent his Italian navigator, Giovanni da Verrazano, to seek the Indies by the western route. Verrazano sailed and charted the coast of North America from Labrador to the Carolinas but did not find a route to Asia. Ten years later, Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence River to an Indian village in Montreal, Canada. His way to China was blocked by the rapids, which he named Lachine (the “China” rapids). But wars, foreign and civil, absorbed the strength of France during the last half of the sixteenth century, and, with one trifling exception, projects of colonization slept until the return of peace and the accession to the throne of King Henry of Navarre in 1598.

War, which was the death of French enterprise, was the very life of English colonial activity, which had languished since John Cabot’s day. England and Spain became bitter rivals — religious, commercial, political — during Elizabeth’s reign from 1558 to 1603. England was fighting for her very life and the life of the Protestant cause against the aggressive Catholic Monarch Philip II. She had no army to attack Philip in his Spanish peninsula, but she sent troops to aid the revolting Netherlands and struck at the very roots of Philip’s power by attacking his treasure-laden fleets from the Indies. England’s dauntless seamen, Hawkins, Davis, Cavendish, and above all Sir Francis Drake, performed marvels of daring against the Spaniards, scouring the coasts of America and the high seas for their treasure ships, fighting single-handed against whole fleets, circumnavigating the globe with their booty, and even sailing into the harbors of Spain to “singe King Philip’s beard” by burning his ships and docks.

From capturing the Spanish gold on the seas to contending with Spain for the possession of the golden land was but a step. Veteran soldier Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in 1578 received a patent from Queen Elizabeth to “inhabit and possess all remote and heathen lands, not in the actual possession of any Christian prince.” Gilbert was unsuccessful in founding a colony on the bleak coast of Newfoundland, and his little ship floundered on her return voyage. His patent was handed on to his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, Elizabeth’s favorite courtier. Raleigh’s ships sought milder latitudes, and a colony was landed on Roanoke Island, off the coast of North Carolina, in 1585. At Elizabeth’s suggestion, the land was named “Virginia” in honor of the “Virgin Queen.” The colonists diligently sought for gold and explored the coasts and rivers for a passage to Cathay.

But, misfortune overtook them, supplies failed to come from England on time, and the colony was abandoned. Again and again, Raleigh tried to found an enduring settlement, but the struggle with Spain absorbed the attention of the nation, and the planters preferred gold hunting to agriculture. Raleigh sank his private fortune in this enterprise and finally abandoned it with the optimistic prophecy to Lord Cecil: “I shall yet live to see it an English nation.” He did live to “see” the beginnings of an English colony in Virginia, but it was from his prison, where he lay under sentence of death, treacherously procured by the envy of the Stuart king who followed the “spacious times of great Elizabeth.”

Wherever the European visitors had struck the western continent, whether, on the shores of Labrador or the tropical islands of the Caribbean Sea, on the vast plains of the southwest or the slopes of the Andes, they had found a scantily clad, copper-colored race of men with high cheekbones and straight black hair. Thinking he had reached the Indies, Columbus called the curious, friendly inhabitants who came running down to his ships Indians. That inappropriate name has been used ever since to designate the natives of the Western Hemisphere.

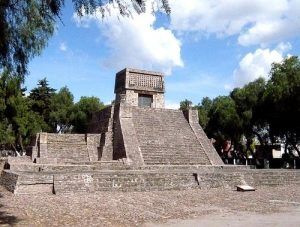

Aztec Pyramid courtesy Wikipedia

In Mexico, Central America, and South America, the Spanish explorers and conquerors found a higher native development in art, industry, architecture, and agriculture than was later found among the Indians of the North. Even the germ of an organized state existed in the Aztec confederacy of Mexico. Huge pueblos, or communal houses, made of adobe, were built around a square or semicircular court in rising tiers reached by ladders. A single pueblo sometimes housed a thousand people. The Aztec and Inca chiefs in Mexico and Peru lived in elaborately decorated palaces.

The Indian tribes north of the Gulf of Mexico had generally reached the stage of development then called “lower barbarism,” a stage of pottery making and rude agricultural science. Midway between the poor teepee, or skin tent, of the Pacific Coast tribes and the imposing pueblo of Mexico, was the ordinary “longhouse,” or “roundhouse,” of the village Indians from Canada to Florida. The house was built of stout saplings, covered with bark or a rough mud plaster.

Along a central aisle, or radiating from a central hearth, were ranged the separate family compartments, divided by thin walls. Forty or fifty families usually lived in the house, sharing their food of corn, beans, pumpkins, wild turkey, fish, bear, and buffalo meat in common. Only their clothing, ornaments, and weapons were personal property. The women of the tribe prepared the food, tended the children, made the utensils and ornaments of beads, feathers, and skins, and strung the polished shells, or “wampum,” which the Indian used for money and correspondence. The men were occupied with war, the hunt, and the council. In their leisure, they repaired their bows, sharpened new arrowheads, or stretched the smooth bark of the birch tree over their canoe frames. They had a great variety of games and dances, solemn and gay, and they loved to bask idly in the sun.

In the beginning, the Indians was generally friendly to the Europeans on their first meeting. It was chiefly the fault of the white man’s cruelty and treachery that the friendly curiosity of the red man was turned so often into malignant hatred instead of firm alliance. Over the years, many tribes died out, while others were almost completely exterminated or assimilated by the whites.

The fairest portion of the continent of North America, which the Spanish adventurers penetrated in the 16th-century, and whose edges the explorers of other nations touched, was destined to become the United States of America. It was blessed by nature with a variety of climates, abundant rainfall east of the Rocky Mountains, wonderfully fertile soil, and priceless deposits of coal and metals.

The mines of South Africa and Mexico alone yield larger supplies of gold and silver. Some lands, like France and Italy, have for centuries had a highly civilized population but have been relatively poor in natural resources; others, like Manchuria and Russia, have been marvelously endowed by nature, while their people have lacked the knowledge and enterprise necessary to exploit their wealth. But, in the United States, men and material were admirably matched. As the tide of migration moved slowly westward, across the Alleghenies, across the Mississippi River, across the Great Plains and the crests of the Rockies and the Sierras, an intelligent and energetic race of pioneers felled the forests, planted the rich river bottoms, and opened the veins of coal and iron.

The process was slow. The early explorers and settlers on the Atlantic Coast had no idea, of course, of the vast continent which lay before them. Even beyond the middle of the seventeenth century, the French explorers believed that the Mississippi River emptied into the South Sea (the Pacific Ocean). The English settlers on the Atlantic Coast did not begin to cross the Alleghenies until far into the eighteenth century. The Rockies were discovered in 1743, and within the next 50 years, the Pacific Coast was charted by explorers and traders. Finally, in 1805, an expedition was sent out by President Thomas Jefferson, which reached the mouth of the Columbia River, linking together for the first time, by the feet of white men, the Atlantic and Pacific shores. That was more than three centuries after the voyages of Columbus and almost exactly two hundred years after, the first permanent English settlement in America.

By David Saville Muzzey, 1920. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Explorers, Trappers, & Traders in American History

About the Article: This article was, for the most part, written by David Saville Muzzey and included in a chapter of his book, “An American History,” published in 1920 by Ginn and Co. However, the original content has been heavily edited, truncated in part, and additional information added.