The Roanoke Colony, also known as the Lost Colony, was the first attempt at founding a permanent English settlement in North America. It was located in Dare County, North Carolina and today is part of the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, which commemorates the first English attempts at establishing a settlement in North America.

The early English colonization of Roanoke Island was a significant event in the gradual process of English settlement in the New World — a process that began with the English explorations of the western hemisphere in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The first English efforts to explore the new continent trace back to King Henry VII, who encouraged English merchants to explore and enter foreign trade. He provided financial backing for John Cabot, the Italian who first visited the New World in 1496. On Cabot’s second voyage in 1497, he planted the first English flag on the North American mainland in Canada.

The King’s granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth I, who came to the throne in 1558, also wanted to explore and exploit the New World and decrease the Spanish dominance that had already been established there. However, during her reign, England did not have the resources to establish a foothold in the New World, so all English enterprises in the Atlantic were financed by private investors who received authorization from the English government to work as privateers. England needed the wealth of the New World to enlarge its boundaries and increase its power and realized that attacking Spanish treasure ships was an ideal way to fight their enemy.

By the 1580s, English privateers were regularly attacking Spanish vessels to control their expanding empire, and in 1584 a major sea war between England and Spain developed. England then sent Sir Francis Drake to raid and plunder Spanish possessions in the West Indies. Many of the early privateers in this open sea war with Spain were gentlemen such as Sir Walter Raleigh, who saw the venture as a patriotic act and a way to amass large fortunes and relieve themselves of financial difficulties.

Earliest Colonization Efforts at Roanoke Island

The first true English colonization efforts, which led to the Roanoke voyages, developed to indirectly attack Spanish possessions during the privateering sea war. They also arose from the continuous search for a Northwest Passage to the Orient. Among the first to propose these measures was Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh’s halfbrother. Gilbert had appealed to Queen Elizabeth to explore the New World and colonize the area for several years. Though Gilbert had proposed this idea as early as 1576, it wasn’t until June 1578 that Queen Elizabeth granted Gilbert a charter authorizing him to “discover, search, find out and view such remote heathen and barbarous lands, countries, and territories not actually possessed of any Christian Prince or people.”

With financial backing from several influential shareholders, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh, and seven ships sailed from Plymouth, England, in November 1578 to establish a colony in Newfoundland. The underlying mission of the expedition was to prey upon Spanish shipping. Storms, however, forced Gilbert to abort the mission and return to England.

In 1583, Gilbert headed another expedition, which ended in disaster when Gilbert was lost at sea. Walter Raleigh, however, did not join the second venture. By this time, he had become a favorite of Queen Elizabeth, who forbade him to sail on such a dangerous voyage. As the Queen’s favorite, Raleigh received vast estates in Ireland and large holdings in England, the patent on wines and the license to export woolen cloths. Other benefits included the assignment of various government offices. In 1584, a year after Gilbert’s death, Queen Elizabeth knighted Raleigh and granted him Gilbert’s patent to establish colonies in America.

Raleigh, like Gilbert, aimed to establish a settlement that would serve as a base for English privateering ventures against Spanish ships. However, Raleigh directed his efforts farther to the south, purposely venturing into Spanish interests to find a semi-secluded location close to Spanish shipping routes from the West Indies. On April 27, 1584, Raleigh’s first expedition left England for the North American coast, but Raleigh did not accompany the fleet.

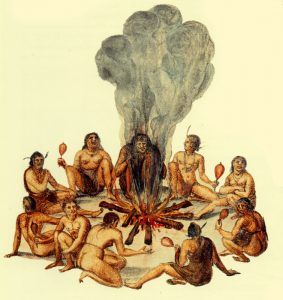

Captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe commanded the two ships and landed on the present-day North Carolina coast approximately 24 miles north of Roanoke Island on July 13, 1584. The expedition made an important contact with local Algonquian Indians, including a well-placed member of a ruling family, Granganimeo. After spending several months in the area, the expedition left for England in September 1584. Along with them were two Algonquian men — Manteo of the Croatoan tribe and Wanchese of the Roanoke tribe. With the help of the two Indians, the captains reported favorably on the Outer Banks area, suggesting that it would be an ideal site for a settlement. With Queen Elizabeth’s permission, Sir Walter Raleigh then christened the new land “Virginia” after her, the Virgin Queen.

The First Colony, 1585-1586

In 1585, Raleigh appointed Sir Richard Grenville, his cousin, to establish a settlement in North America. Grenville, another well-known privateer, sailed from England in 1585 with seven vessels and approximately 600 men, nearly half of whom were professional soldiers or specialists. Captain Amadas and Navigator, Simon Fernandes, who were with the first expedition, were also the group, as well as Ralph Lane, a fortifications expert; John White, an artist to record the landscape and flora and fauna, Thomas Hariot, a scientist to collect samples; and Joachim Gans, a metallurgist to assess the commercial potential of the land. The two Native Americans, Manteo and Wanchese, also returned to America on this voyage.

The expedition first arrived in Puerto Rico on May 12, where they made repairs, captured two Spanish frigates, and seized a supply of salt from the Spanish. Grenville’s expedition landed on the Outer Banks of North Carolina on June 26. After a brief exploration of the Outer Banks and Roanoke Island and making contact with the local Indians, Grenville departed for England on August 17, 1585, promising to return in April 1586 with more men and fresh supplies. He left Ralph Lane in charge of a colony of 107 men on Roanoke Island.

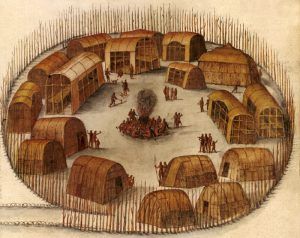

Since the site was too shallow for a privateering base, Ralph Lane used Roanoke as a base to search for a more suitable harbor site. Lane then designed and supervised the construction of a fort at the north end of Roanoke Island. It was completed by September. His men also erected a “science center” on the island’s north end to assess the area’s resources and commercial potential. Other improvements included a separate village on the north end of Roanoke Island containing one-and-a-half- and two-story residences with thatched roofs and several other structures. Although some of the soldiers were stationed at the fort, Ralph Lane and several gentlemen on the expedition resided in the village.

The following year, Lane and several colony members explored the mainland and surrounding area as far north as the Chesapeake Bay. In these explorations, Lane and his men succeeded in alienating a large portion of the Native American population, resulting in hostile relations between the two.

As April 1586 passed, there was no sign of Grenville’s relief fleet. With the delay in the arrival of supplies, the colonists grew impatient as provisions ran out, and relations with the indigenous population continued to deteriorate. The local Indians attacked the fort, but the colonists were able to repel it. In June, Sir Francis Drake stopped at the colony on a return trip after a successful raid in the West Indies. Drake offered to take the colonists back to England, and they accepted, missing one of Grenville’s supply ships by only a short time. In August, Grenville arrived with several ships and relief stores and was disappointed to see the colony abandoned. He did not want to lose possession of the settled area and left a small detachment of 15 men with four cannons and supplies for two years to maintain an English presence and protect Raleigh’s claim to Roanoke Island. When the colonists returned to England, they introduced tobacco, maize, and potatoes.

The Lost Colony, 1587

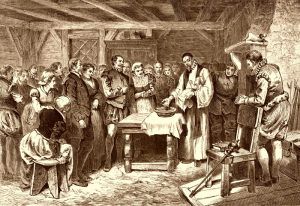

The following year, Sir Walter Raleigh organized another expedition to Virginia under the leadership of John White, who had accompanied Grenville on his voyage in 1585. As opposed to previous ventures, this one was less military and more civilian in nature. Of the 150 people John White assembled for the voyage, 84 men were referred to as “planters,” and the group also included 17 women and nine children. The group included John White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare.

Unfortunately, the expedition was compromised from the beginning. The failures of the previous expedition to find a suitable base from which to privateer, coupled with the lack of discovery of precious metals and other supposed treasures, led many investors to begin withdrawing support. Sir Walter Raleigh himself, even though still supportive of the idea of an English foothold in the New World, began to show a decreased enthusiasm for the venture; the colonization attempt had already cost him 30,000 pounds, a steep sum in the 1580s. Nevertheless, plans for the expedition continued.

John White and the colonists met in London in the spring of 1587 and departed in three small ships in May. After stopping in the Caribbean, they arrived off the Outer Banks on July 16. On July 22, White and the colonists went to Roanoke Island to confer with the 15 men left by Grenville the preceding year. White hoped to learn about the area and their relations with the Indians and then return to the ships to sail to the intended site of his colony, the Chesapeake Bay area. The Chesapeake Bay was chosen because it would be a better port, and conditions for settlement were more favorable.

The Lost Colony Historical Drama has played in Manteo, North Carolina since 1937, photo by Carol Highsmith.

When the colonists arrived at Roanoke, Lane’s former fort was abandoned and Grenville’s holding party was missing. They found the sun-bleached skeleton of one of Grenville’s men, who had long since been killed, and suspected that the others had also been killed. Afterward, the flotilla’s captain, Simon Fernandes, refused to take the colonists farther up the coast, with his excuse being that summer was rapidly ending. He then left White and the colonists on Roanoke Island.

Upon discovering the fort overgrown and abandoned, White immediately ordered the colony members to refurbish Lane’s former settlement. They began their work optimistically, cleaning and repairing the existing dwellings and building additional shelters so each family would have its own residence.

The colony wasn’t under a military government but operated under Governor John White and his 12 assistants, who served as a board of directors. The new colony was called the “Cittie of Ralegh,” and the colonists could take roles in its leadership and profit from their own efforts. However, the initial optimism was checked within a few days of their arrival when one of the colonists, George Howe, was killed by an unidentified party of Native Americans. But, White placed his hopes on his ability to reestablish good relations with the Algonquian residents and was helped by Manteo, the Croatoan Indian, who traveled to England with Lane a second time and returned with White.

White and the colonists discovered that three settlements of Native Americans had joined together and attacked 11 of Grenville’s men. The soldiers who survived the assault fled by boat and disappeared. White undertook a punitive expedition to avenge these deaths, raiding an inland settlement and killing at least one of its members as a gesture of strength. Unfortunately, the group that White’s colonists attacked was unconnected to Howe’s death or that of the soldiers who were part of the holding party. The colonist attack caused the remaining friendly Native American groups to become wary of this second colony.

Another major problem for the settlement was the lack of supplies. Their arrival late in the planting season resulted in inadequate stores for the winter. The local inhabitants had little to share, and this scarcity created more tension.

Despite the tension, the colony celebrated on August 13, when following Sir Walter Raleigh’s orders, Manteo was christened and given the title of Lord of Dasamonguepeuc for his faithful service to the English. Five days later, Eleanor Dare, daughter of John White and wife of Ananias Dare, gave birth to a daughter. Because she was the first child born to English parents in America and the first Christian born in Virginia, she was named Virginia.

Having delivered the colonists, the fleet was scheduled to leave in August. The colonists wanted more supplies and more members to be recruited and asked John White to return to England to act for them. Though White was concerned about the safety of his daughter and granddaughter, he agreed to return. The fleet sailed for England on August 27, but before White left, he arranged for the colonists to leave an appropriate sign if they moved the settlement.

In October, White arrived in England, but his efforts to obtain support were impeded by the Spanish Armada’s attempted invasion of England and the subsequent sea war between the two countries. Sir Walter Raleigh, being so close to Elizabeth I, was forced to abandon White’s request to resupply Roanoke. Instead, he assisted with the repulsion of the Spanish Armada that was at England’s front door. Further, Queen Elizabeth I ordered all English vessels to remain nearby in defense of the homeland.

After the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Raleigh’s interest in colonization began to shift to Ireland, forcing White to turn to other investors to acquire revenue for the journey. It was not until early 1590 that White convinced a group of privateers bound for the West Indies to take him to Roanoke.

In March 1590, White sailed as a passenger on a ship commanded by the privateer John Watts and finally reached the Outer Banks in August 1590. Upon his arrival, he could see that the colony had been abandoned for some time and found the word “C-R-O-A-T-O-A-N” inscribed into a palisade, which indicated a native group who lived on what is now Hatteras Island. There were no signs of a struggle or the colonists leaving in haste. Although White could not locate the colonists, he was relieved to discover a sign of their safety.

The ship then sailed to Croatoan, but because of stormy weather and John Watt’s impatience, White could not continue the search for the missing colonists on the Outer Banks and returned to England.

“About the place, many of my things spoiled and broken, and my books torn from the covers, the frames of some of my pictures and Maps rotted and spoiled with rain, and my armor almost eaten through with rust.”

— John White

Afterward, White could not afford to finance another expedition to North America and eventually accepted the loss of his family and the Roanoke colony several years later. Sir Walter Raleigh, however, made one more attempt to locate the settlement. As late as 1602, Raleigh sent an expedition to North America under the command of Samuel Mace to find the colonists. However, the group did not search very diligently and never found these early settlers. After the establishment of Jamestown in 1607, the Virginia colonists attempted to locate their lost countrymen. Although they heard many rumors as to their whereabouts, the search was unsuccessful. In the meantime, John White disappeared from the historical record and is thought to have died, possibly in Ireland, around 1606.

Many scholars have since proposed numerous theories about what happened to the Roanoke colonists, but their fate remains a mystery.

Later English Colonization

While the Roanoke Island colony was unsuccessful, it set a precedent for future English colonization efforts in the New World. It also marked the transition from military outposts to settlements of men and women attempting to establish a permanent foothold in North America.

Elizabeth II, a representative 16th-century sailing vessel in Festival Park in Manteo, Roanoke Island, North Carolina by Carol Highsmith

English vessels began to make reconnaissance voyages along the Atlantic coast, and numerous settlements would be established in the decades. These included Jamestown, Virginia in 1607; Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620; New Jersey in 1629; Connecticut in 1633, Rhode Island in 1636, Maryland in 1637; and Delaware in 1638.

The Fort Raleigh National Historic Site preserves the location of the lost colony and commemorates the first English attempts at establishing a colony in North America.

©Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated August 2021.

Also See:

Discovery and Exploration of America

Sources:

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

National Park Service Publications

Wikipedia