Scattered across Texas from the Red River to the Rio Grande are the remains of a once-formidable military presence on the frontier — Texas’ 19th-century forts. Though the Texas Forts Trail can’t possibly cover the more than four dozen old forts and presidios across the vast Lone Star State, this 650-mile Scenic Byway certainly provides a glimpse into many of these lonely outposts that were once situated on the dangerous hills and dales of central Texas.

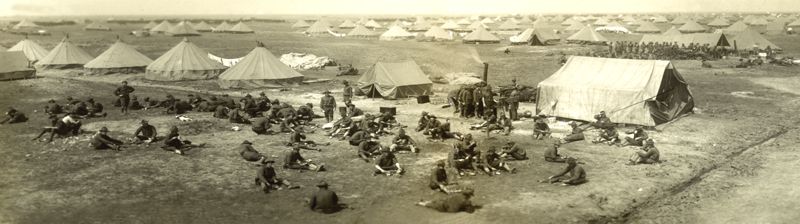

From 1848 to 1900, the U.S. Army built 44 major posts and set up more than 100 temporary camps in Texas. In addition to the many military forts established by the U.S. Army, several earlier Republic-era forts, private bastions, and Spanish Presidios were built and abandoned across the Lone Star State. Today, these sites range from ghostly ruins to historically accurate reconstructions to nothing but a historical marker to identify their locations.

During the 19th Century, settlers streamed west onto the advancing frontier, invading the territorial lands of the Native Americans who had long called this area home. Resentful of the influx of white settlers upon their domain, the Kiowa, Comanche, and other Plains Indians fought back in raids and attacks on caravans and settlements. But, the encroaching settlers were not deterred and continued to invade Texas, assisted and protected by the many soldiers stationed at the frontier posts.

Texas seceded from the Union when the Civil War began, and all federal garrisons were ordered to evacuate all the posts and surrender them to Confederate authorities. When the war ended, the U.S. Army returned to Texas to stay until the frontier was tamed.

The duties of the soldiers at the many posts were to escort wagon trains and the mail, patrol their segments of the road, keep track of the Indians’ whereabouts, and pursue and punish any Indian raiders. Over the next 15 years, these tasks would be continued, eventually eliminating the Indian resistance to white settlement in Texas.

In September 1874, one of the latest engagements of Indian fighters began when Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie led his Fourth United States Cavalry from the south to trap the Indians in their refuge at Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle. Mackenzie’s troopers formed part of the Red River Campaign of 1874-75, who were organized to force the Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Comanche to return to the reservations.

On September 28th, Mackenzie’s scouts followed the Indian trail to the edge of Palo Duro Canyon before the soldiers descended the steep slopes to the valley floor 700 feet below. Taken by surprise, the Indians abandoned their villages, allowing Mackenzie to capture more than 1,100 horses that were later slaughtered to prevent recapture. Although few Indians or soldiers were killed, the unrelenting pursuit of the troopers and the cold weather ultimately forced the Indians to surrender, thus bringing to a close the Red River War.

During the five years after Mackenzie’s victory, white hunters converged upon the Plains and systematically slaughtered the great southern buffalo herd for the animals’ hides and for sport. Fort Griffin and the nearby raucous village called “The Flat” became the center of the buffalo hunters, as well as gamblers, prostitutes, gunmen, and thieves, bent on relieving the hunters of their money. By 1881, the Comanche presence and the buffalo were gone, so the army closed Fort Griffin.

But, in the Trans-Pecos region, the army was still fighting, mainly against the Apache. They were raiding across the Rio Grande from strongholds in the mountains of Chihuahua and Coahuila. In September 1879, a large band of Mescalero and Warm Springs Apache, under the leadership of chief Victorio, began a series of attacks west of Fort Davis. Troops from around the region were ordered to guard the region’s few watering holes. After several hard-fought battles, Victorio and his thirsty men crossed back into Mexico. This was the last major conflict between Indians and the U.S. Army on Texas soil.

With the Indians gone, the remaining forts settled into a quiet garrison routine. Eventually, one by one, the forts were shut down.

Today the Texas Forts Trail follows a path that provides visitors with a peek into the lives of pioneers, soldiers, and Native Americans that helped to establish the Lone Star State. The trail provides a virtual road to eight of the state’s remarkable frontier forts of West in Central Texas, where today’s visitors can walk in the paths that were once traveled by the likes of Robert E. Lee, John Butterfield, Buffalo Hump, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and more. The byway also provides several other interesting destinations along the trail, including state parks, some 20 lakes, seven state parks, and dozens of museums.

Fort Richardson

More Information:

Texas Forts Trail

3702 Loop 322

Abilene, Texas 79602

325-795-1762

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2022.

Also See:

Forts & Presidios Across America

Forts & Presidios Photo Gallery

Byways & Historic Trails – Great Drives in America

Sources: