In American history, St. Clairs Defeat was the worst defeat of an army by indigenous forces. Art by Peter Dennis from Osprey’s “Wabash 1791: St Clair’s Defeat.”

St. Clair’s defeat, also known as the Battle of the Wabash or the Battle of a Thousand Slain, was fought on November 4, 1791, in the Old Northwest Territory in present-day Ohio. When the U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of Native Americans during the Northwest Indian War, it suffered “the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military” and its largest defeat ever by Native Americans.

Many Americans are familiar with other battles and names of the Indian Wars, such as Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, George Armstrong Custer, and the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. However, few are aware of the worst disaster experienced by the U.S. Army at the hands of Native Americans, which occurred 85 years before Custer’s last stand. The defeat greatly overshadowed Little Big Horn in terms of casualties, brutality, and consequences.

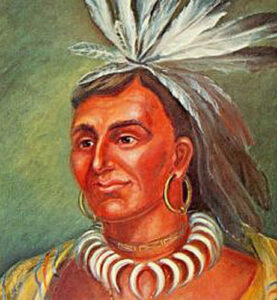

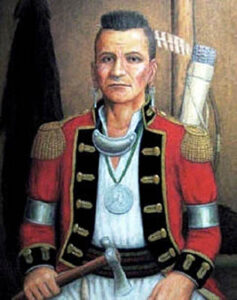

In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, Great Britain recognized the United States’ control of all the land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes. The native tribes in the Old Northwest, however, were not parties to this treaty, and many of them, especially leaders such as Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee War Chief Blue Jacket, refused to recognize American claims to the area northwest of the Ohio River. The young United States government, deeply in debt following the Revolutionary War and lacking the authority to tax under the Articles of Confederation, planned to raise funds by selling land in the Northwest Territory. This plan called for the removal of both Native American villages and squatters. During the mid and late 1780s, a cycle of violence in Indian-American relations and the continued resistance of Native nations threatened to discourage American settlement of the contested territory, so Judge John Cleves Symmes and Jonathan Dayton petitioned President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox to use military force to crush the Miami tribe.

In 1790, two years after the ratification of the Constitution, the United States faced a challenge to its authority by the tribes of the Old Northwest Territory. This area included Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Indian tribes attacked American settlers at the encouragement of British agents from Canada and British troops still occupying various installations, which was a direct violation of the peace treaty that ended the American Revolution.

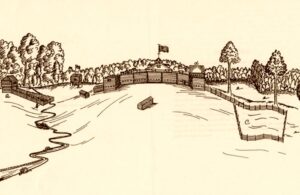

As a result, President George Washington dispatched an expedition led by Brigadier General Josiah Harmar to quell the Miami Indian raids led by Miami Chief Little Turtle. On October 7, 1790, a force of 1,453 men, including 320 regulars from the First American Regiment and 1,133 militia, under General Josiah Harmar marched northwards from Fort Washington (now Cincinnati, Ohio.) They aimed to battle against the Miami Settlement of Kekionga and Fort Miami (present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana), the center of Indian resistance to U.S. migration across the Ohio River.

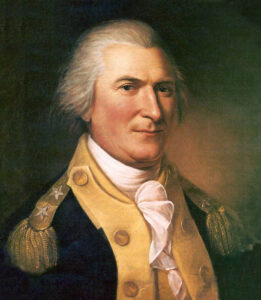

Between October 19 and October 22, Harmar committed detachments that were ambushed by Native American forces defending their territory. On three separate occasions, Harmar failed to reinforce the detachments and ordered a retreat back to Fort Washington after suffering more than 200 casualties and the loss of a third of his packhorses. Estimates of total Native casualties, killed and wounded, range from 120 to 150. Harmar was soundly defeated and forced to withdraw because of supply shortages and poor military planning. Afterward, another force was organized to march into the Northwest Territory to confront the now-confident Chief Little Turtle and his followers. Major General Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory and a Continental Army veteran was ordered to mount a more vigorous effort by the summer of 1791.

The force included the First American Regiment, a second infantry regiment, 800 six-month volunteers organized into two regiments of levies, Kentucky militia, and a few cavalry, bringing the army’s strength to 1,400 men. Though President Washington was adamant that St. Clair move north in the summer months, various logistics and supply problems considerably slowed his preparations.

In the meantime, in May 1791, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson was ordered to lead another raid in August, intended to create a distraction that would aid St. Clair’s march north. In the Battle of Kenapacomaqua, Wilkinson killed nine Wea and Miami Indians and captured 34 Miami as prisoners, including the daughter of Miami war chief Little Turtle. Many confederation leaders considered peace terms to present to the United States, but when they received news of Wilkinson’s raid, they readied for war. Wilkinson’s raid thus had the opposite effect, uniting the tribes against St. Clair instead of distracting them. St. Clair’s horrific defeat would take place shortly after.

Major General Arthur St. Clair, plagued by illness and, some believe, unfit to command the expedition, set out with his force from Fort Washington in September 1791. His recruits were poorly trained and undisciplined, his food supplies were substandard, and the horses were few and poor quality. Along the way, St. Clair ordered his army to build a series of forts along the route of advance through hostile country, which slowed the army’s progress. By November, St. Clair’s force was only 90 miles from where it had started. The troops, composed primarily of volunteer militia, experienced desertions from the campaign’s onset. Faced with frigid temperatures and constant supply troubles, the men were weakened and demoralized when they reached the banks of the Wabash River. St. Clair further weakened his army by detaching the First American Regiment to look for their late supply train.

Going was slow, and discipline problems were severe; St. Clair, suffering from gout, had difficulty maintaining order, especially among the militia and the new levies. Indians constantly shadowed the force, and skirmishes occasionally erupted. By November 2, through further desertion and illness, St. Clair’s force had been whittled down to around 1,120, including the camp followers. While St. Clair’s Army continued to lose soldiers, the Western Confederacy quickly added numbers.

On November 3, St. Clair’s force camped on an elevated meadow near the headwaters of the Wabash River, near the present-day location of Fort Recovery, Ohio. Dangerously, the First Infantry and volunteers encamped on the opposite side of the Wabash River from the Kentucky militia camp, making it challenging to assist one another. No defensive works were constructed, even though natives had been seen in the forest. Major General Richard Butler commanded the levy regiments and sent a small detachment of soldiers under Captain Jacob Slough to capture some warriors who had harassed the camp. The detachment fired on a small party of Native Americans but soon realized they were outnumbered. They returned to the camp and reported to Major General Richard Butler, the Army’s second in command, that they believed the enemy would attack in the morning. However, General Butler did not convey their message to General St. Clair, who had already gone to bed for the night. Butler also did not order any extra protective measures against an attack. At that time, St. Clair had 52 officers and 868 enlisted and militia present for duty.

That night, a native force of around 1,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle, established a large semicircle surrounding the camp. On the morning of November 4, 1791, Miami Chief Little Turtle, Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket, and Delaware Chief Buckongahelas led a war party of over 1,000 warriors, including many Potawatomi from eastern Michigan across the river, against St. Clair’s force. Egushawa was among the leaders of the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe units. Simon Girty was among the leaders of the Wyandot, Mingo, and Cherokee units that formed the right wing. Ironically, Adjutant General Winthrop Sargent had just reprimanded the militia for failing to conduct reconnaissance patrols when the natives struck, surprising the Americans and overrunning their ground.

When the Indians charged the main line, the militiamen fled across the Wabash River and up the hill to the main camp without their weapons. The regulars immediately broke their musket stacks, formed battle lines, and held the line with musketry and bayonets. Leading the charge, St. Clair had two horses shot out from under him, received several bullet holes in his clothing, and had a lock of hair shot away.

The artillery fired its cannons but had little effect because the guns were aimed too high. However, the left and right wings of the Native American formation flanked the regulars and closed in on the main camp, meeting on the far side. Within 30 minutes, the warriors had entirely encircled the St. Clair’s camp. The U.S. muskets and artillery were of poor quality and had little effect on the Native warriors behind their cover. As a result, the artillerymen fought in hand-to-hand combat with the Indians until most of them were dead. Women who accompanied the army fought desperately alongside the men and were also among the slaughtered. Major General Richard Butler, who was in command of the levy regiments, was shot twice and died in his tent. He was the first of four American generals killed in the Indian Wars.

After three hours of fighting, St. Clair finally ordered a retreat to Fort Jefferson. A bold bayonet attack under Colonel William Darke opened a route for those able to escape.

Private Stephen Littell became lost in the woods and accidentally returned to the abandoned camp. He reported that the Native Americans were all gone in pursuit of the fleeing army. The remaining wounded begged him to kill them before the Native Americans returned. The American Indians continued their pursuit, killing those who fell to the rear of the retreat. After they had gone about four miles, they returned to loot the camp. Hiding beneath a tree, Littell reported that they ate the abandoned food, divided the spoils, and scalped, tortured, and murdered the wounded, including women and children.

The head of the retreat reached Fort Jefferson that evening, a distance of nearly 30 miles in one day. With inadequate space and no food, it was decided that those who could continue to Fort Hamilton, another 45 miles away. The wounded were left at Fort Jefferson with little or no food. Those on horseback reached Fort Hamilton the next morning, followed by those who marched on foot.

St. Clair sent a supply convoy and a hundred soldiers under Major David Ziegler from Fort Washington on November 11. At Fort Jefferson, they found 116 survivors eating “horse flesh and green hides.” Charles Scott organized a relief party for the Kentucky militia, but it disbanded at Fort Washington in late November, and no action was taken. Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson assumed command of the Second Regiment in January 1792 and led a supply convoy to Fort Jefferson. The detachment attempted to bury the dead and collect the missing cannons, but the task was beyond it, with “upwards of six hundred bodies” at the battle site and at least 78 bodies along the road. The exact number of wounded is not known, but it has been reported that execution fires burned for several days after the battle.

Of the 1,400 regulars, levies, and militia, 918 were killed and 276 wounded. Almost half of the entire U.S. Army was either dead or wounded in the aftermath of St. Clair’s Defeat. The casualty rate was the highest percentage ever suffered by a United States Army unit and included St. Clair’s second in command, Richard Butler. Of the 52 officers engaged, 39 were killed and seven wounded; around 88% of all officers had become casualties. The American casualty rate among the soldiers was 97%, including 632 of 920 killed and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were slaughtered, and a total of 832 Americans were killed. Due to its relatively small size at the time, approximately one-quarter of the entire U.S. Army had been destroyed in one day.

St. Clair sent news of the defeat to Secretary of War Henry Knox and President George Washington, who demanded St. Clair’s resignation. Congress was in a state of shock and ordered an investigation into the defeat. Secretary of War Henry Knox assessed that the Army was deficient in the number of disciplined troops and had been operating too late into the year. The House committee conducting the investigation eventually found that St. Clair’s defeat was due to inadequate forces, gross mismanagement by the quartermaster and contractors, and the lack of discipline and experience in the troops. St. Clair received no blame for the disaster and was permitted to continue as governor of the Northwest Territory until 1802.

In early 1792, Congress authorized an increase in the size of the Army and the creation of the Legion of the United States. President Washington selected Major General “Mad Anthony” Wayne to command this new force and was named commander-in-chief of the Army. On August 20, 1794, Wayne achieved what St. Clair could not and defeated the Indians in less than one hour and a half at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near today’s Maumee, Ohio. The Battle of Fallen Timbers ended the Miami Campaign and helped establish the U.S. Army’s proud heritage of victory. The new Legion of the United States also brought the first displays of excellence and professionalism to be the foundations of the Regular Army.

So many people died on site that when 300 soldiers from the Legion of the United States returned to the scene in late 1793, they identified the site by the unburied human remains. The detachment had to move bones to make space for their beds. The Legion buried remains in a mass grave. Sixty years after the battle, in September 1851, the town organized Bone Burying Day to inter the remains of bones discovered.

Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2024.

Also See:

Battles and Massacres of the Indian Wars

Sources:

Arch Fort Wayne

Army Historical Foundation

U.S. Army

Wikipedia