Henry and Naomi Sager, along with their six children joined a wagon train led by Captain William Shaw at the end of April 1844 in a quest for a better life. The parents wouldn’t survive the trip and the children would suffer more tragedy before their ordeal was complete.

Years later, Catherine Sager would describe her father, Henry Sager, as “a restless one.” Before 1844, he had moved his growing family three times. They started in Virginia before moving to Ohio and then Indiana before finally arriving in Platte County, Missouri in the Autumn of 1843. There, he engaged in farming and blacksmithing. Temporarily settling in St. Joseph, Missouri, a jumping-off point for the Oregon Trail, Henry almost immediately began to make plans to travel to Oregon. His wife, Naomi, was reluctant to go at first, but eventually agreed.

In March 1844 Henry joined a group of pioneers who called themselves The Independent Colony. A month later, the family, including their six children: John 14, Frank 12, Catherine 9, Elizabeth 7, Matilda 5, and Louisa 3 years old, crossed the Missouri River and started out on the 2,000-mile journey along the Oregon Trail. The wagon train included 300 people in 72 covered wagons.

After five weeks on the trail, Naomi would give birth to their seventh child on May 30, 1844, in present-day Kansas. They named her Henrietta. Catherine recounted;

“The first encampments were a great pleasure to us children. We were five girls and two boys, ranging from the girl baby to be born on the way to the oldest boy, hardly old enough to be any help.”

On July 4, 1844, the wagon train celebrated Independence Day on the banks of the Platte River in Nebraska. A couple of days later, they forded the South Platte River, where Henry Sager lost control of his oxen. The wagon overturned in the shallow waters along the bank and Naomi was injured, but the pioneers pressed on.

Chimney Rock in Nebraska, by Kathy Alexander. A number of other trails followed the Oregon Trail for part of its length. These include the Mormon Trail from Illinois to Utah and the California Trail to the goldfields of California.

In late July, they passed Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff in western Nebraska. It was the reminder that the Great Plains were almost crossed and the Rocky Mountains lay ahead.

Not too far from the north bank of the Platter River, near Fort Laramie, Wyoming, Catherine, age 9, tried to jump out of the wagon while it was in motion. Unfortunately, she caught her dress on an ax handle and she was thrown under the wagon. Lucky for her, a doctor who was on the journey saved her leg but she would be confined to the wagon for the rest of the journey. They pushed on that same night until they reached Fort Laramie.

A couple of days later the Independent Colony reached Independence Rock, and on August 23, 1844, the wagon train reached South Pass on the Continental Divide. During the descent into the Green River Valley some of the travelers, including Henry Sager, fell ill due to an outbreak of camp fever.

After crossing the Green River, two women and a child had died of the fever and Henry was very ill. Knowing that death was imminent, he asked Captain Shaw to take care of his family. The next day, he was buried on the banks of the river in an improvised coffin and the wagon train traveled on.

Wagon Train

Naomi was torn with grief and was still weakened from childbirth. Although Captain Shaw and the doctor did everything possible to assist her, the exertions were too much and she too soon fell ill with the fever. After reaching Fort Bridger, Naomi had become delirious and asked the doctor to deliver the children to the Whitman Mission in the Walla Walla Valley in present-day southeastern Washington. She died near present-day Twin Falls, Idaho. In 26 days the Sager children had lost both parents and were left orphaned.

The children were cared for by other families in the wagon train and the caravan pressed on. In early October, word was sent ahead to the Mission to let them know that a needy wagon train was approaching and to talk with them about adopting the Sager children.

Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, sent word back to the wagon train that they would take all seven. A few days later, after six months and 2,000 miles, Henry and Naomi Sager’s children finally reached their new home in Oregon.

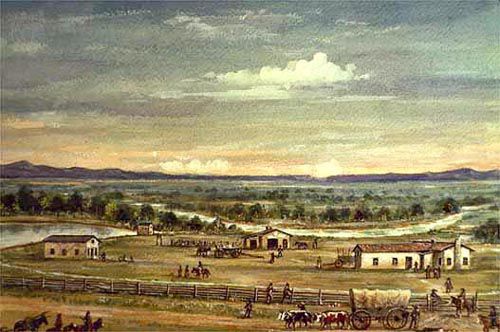

Whitman Mission

In July 1845 Dr. Whitman obtained a court order giving him legal custody the children, but, tragedy would continue to follow them. The Whitman Mission ministered to the Cayuse Indians and had maintained peaceful relations with them. However, as more and more settlers passed through on wagon trains, disease came with them, striking distrust and animosity among the Indians.

The peaceful coexistence of the local Cayuse and the white missionaries was in a delicate balance, and in 1847, the balance began to shift to distrust and animosity.

In 1847, three years after the arrival of the Sager orphans, an outbreak of measles decimated the Indian tribes of the area and the Cayuse held white settlers responsible. As a result, the Cayuse attacked the Whitman Mission in November. Known as the Whitman Massacre, the attack claimed 14 lives at the mission including Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the two Sager boys, John and Frank. The 54 women and children were taken captive and held for ransom. Several of the prisoners died in captivity, mostly from illnesses such as measles, including Louisa Sager.

A month after the massacre, Peter Ogden of the Hudson’s Bay Company arranged for the release of the women and children by trading blankets, clothing, rifles, and ammunition. They were then brought to Fort Vancouver and released into freedom.

Catherine, Elizabeth, and Matilda Sager, 1897

The four remaining Sager girls were split up and sent to different families. Henrietta died young at age 26, supposedly mistakenly killed by an outlaw. The other three girls, Catherine, Matilda, and Elizabeth all married, had children and lived well into old age.

About 1860 Catherine, the oldest girl, wrote a first-hand account of their journey across the plains and their life with the Whitmans. Today, “Across the Plains in 1844″, by Catherine Sager Pringle is regarded as one of the most authentic accounts of the American westward migration.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated February 2020.

Also See:

Adventures and Tragedies on the Overland Trail

Tales & Trails of the Frontier

Sources: