Etienne Veniard de Bourgmont was a French explorer who documented his travels on the Missouri and Platte Rivers in North America and made the first European maps of these areas in the early 18th century.

Bourgmont was born in 1679 in Cerisy Belle-Etolie, Central Normandy, France. At the age of 19, Bourgmont was found guilty in 1698 of poaching and fled to North America to escape imprisonment for not paying his fines.

In 1702, he enlisted as a soldier in the Ohio Valley, and in 1706, he became the commander of Fort Ponchartrain in Detroit, Michigan. He was censored for his handling of a battle with the Ottawa tribe but fled before authorities could capture him. From 1706 to 1709, he lived as an illegal trader with several other deserters in the wilderness. He then went to the Missouri River, where he lived for several years among the Indians.

In 1712, Bourgmont married the daughter of a Missouria Indian chief. In 1713, Bourgmont and two other traders visited Illinois, where “He scandalized the missionaries, rattled the authorities, and even angered certain exalted personages at the court of Louis XIV.” When an order for his arrest was made, he fled to Mobile, Alabama. While there, he wrote the “Exact Description of Louisiana, Its Harbors, Lands, and Rivers, and Names of Indian Tribes That Occupy It, and the Commerce and Advantages to Be Derived From the Establishment of a Colony.” In the meantime, his Missouria wife bore him a son in 1714 named “le Petit Missouria.”

While traveling back to the Missouri tribe along the Missouri River, he wrote: “The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River.” He traveled further up the Missouri River than any previous explorers. In 1719, he was sent to make alliances with the American Indian tribes and to bring their leaders to Isle Daphine in Alabama, but all the chiefs except one died along the way. After escorting the one chief back to his village, Bourgmont went to New Orleans, Louisiana.

In June 1720, he and his Missouria son traveled to Paris, where they were greeted as heroes. While there, Bourgmont was commissioned as a captain in the French army and, in August, was named “Commandant of the Missouri River.

In May 1721, he returned to France, where he gained honors for his explorations and reports in Paris. While there, he married Jacqueline Bouvet des Bordeaux in his home village in Normandy and left in June to return to New Orleans.

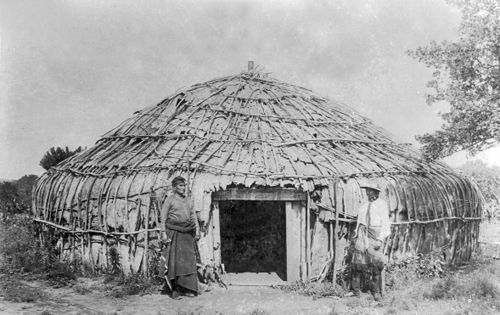

In 1723, due to his familiarity with the country and his acquaintance with the natives, he was selected by the French to lead an expedition up the Missouri River. His first work was to erect Fort Orleans, the first European fort on the Missouri River, near the mouth of the Grand River and present-day Brunswick, Missouri. The fort was built as a means of holding the allegiance of the Indians to the French and guarding against Spanish invasion or interference. There, he established his headquarters.

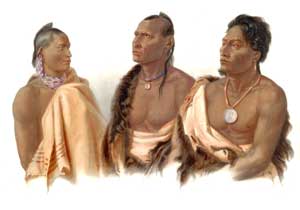

In July 1724, he led an expedition to the Great Plains of Kansas to establish trading relations with the Apache Indians. He soon came upon a large Kanza village near Doniphan, Kansas, where he made them several gifts. Several young warriors agreed to accompany him on his expedition. However, Bourgmont soon became ill, and the party returned to the Kaw village. Bourgmont then sent an emissary to contact the Apache, telling them that he would be coming soon and bringing two Apache slaves to be returned to the tribe as an expression of goodwill. By October, Bourgmont had recovered and traveled again to meet the Apache.

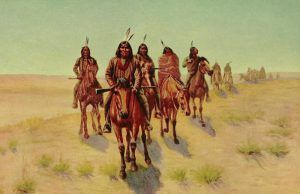

The party proceeded southwest, and on October 11, at the crossing of the Kansas River near present-day Rossville, Bourgmont recorded seeing buffalo. On October 18, the group came upon the Apache, who rode out on horses to meet the French and took them back to the camp. Bourgmont was given an honored welcome, and with his son and two other French explorers, he was seated on a buffalo robe and provided a great feast.

The next day, Bourgmont assembled his trade goods, including guns, knives, tools, cloth, mirrors, clothing, and more. The Padouca Apache had never seen such a variety of European goods and were frightened of the guns. After assembling 200 of the Apache chiefs, he negotiated peace and implored them to allow the French traders to pass through their lands en route to the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. Next, he invited the chiefs to take what they wanted of the merchandise. Bourgmont and his group returned eastward to the Kanza village on October 22 and reached Fort Orleans on November 5.

Bourgmont thought his expedition had been successful, but little came of it. Within about a decade, the Apache whom he had met in Kansas had been pushed south by an aggressive tribe of Comanche who had migrated from the Rocky Mountains.

In 1725, he accompanied a delegation of four leaders from the Illinois, Missouria, Osage, and Otoe tribes on a visit to France. His Missouria wife traveled with him, and while there, she was baptized and married to Bourgmont’s close colleague, Sergeant Dubois. Later, Dubois returned to America with the Indian chiefs and his new wife, while Bourgmont stayed in France, joining his French wife Jacqueline in Normandy.

Indians later killed Sergeant Dubois, and the Missouria woman married a militia captain. She was still alive, living in Kaskaskia, Illinois, in 1752. The fate of Bourgmont’s Missouria son is unknown, as his last record was in 1724. De Bourgmont lived in France for the rest of his life and died in 1734.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank, Kansas Cyclopedia, Standard Pub. Co., 1912

Kansas State Historical Society

Wikipedia