Doniphan, Kansas, is a ghost town in southeast Doniphan County along the Missouri River. This muddy river would be the reason for the establishment of Doniphan, its growth, and finally, its end.

Long before white settlers came to the area, Kanza Indians lived here. In 1724, the region was explored by Frenchman Etienne Veniard De Bourgmont, who found the Indians living in sod-covered dwellings along the creeks and rivers. In the late 1700s, the Kanza Indians relocated for unknown reasons.

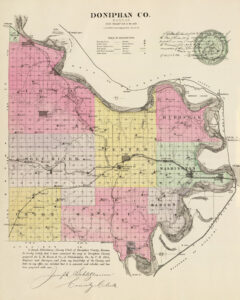

In 1852, Josephus Utt, an agent for the Kickapoo Indians, erected a trading post near the riverbank below what would soon become the townsite of Doniphan. This area had long been known by boatmen up and down the river as an excellent landing point. The steamboat traffic, excellent rock-bound landing, and the abundant woods in the area prompted the organization of a town company. On November 11, 1854, organizers of the Doniphan Town Company met at St. Joseph, Missouri, to elect officers. In the spring of the following year, a townsite situated on the river bluffs above the river was surveyed by James F. Forman. Forman was paid for his services in his choice of town lots and constructed the first building, which soon housed the Forman Brothers Store. Forman became the first postmaster when a post office was established in the store on March 3, 1855. The town and the county were named for General Alexander William Doniphan, who had distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War.

The sale of town lots began on April 15, 1855, with some going for as much as $2,000. Within no time, there were other incoming businesses and settlers building homes. That year, the fledgling city welcomed a lawyer named Colonel D. M. Johnson, Allen B. Lyon, who ran a dry goods store, I.N. Smallwood, a wagonmaker that was said to have been kept very busy; a tinsmith named Patrick Laughlin, who made tin pans and coffee pots; William Beauchamp, a blacksmith, and Samuel Collins who set up the first sawmill. Bowdell & Drury operated the first drugstore. George A. Cutler was the first physician, and the first hotel was built by Forman Brothers and called the Doniphan House. It was opened and run by Barney O’Driscoll. Two large warehouses that could accommodate 15 boats daily were built along the wharf. The first election was held in October 1855. The first religious services in Doniphan were held by Father Alderson, a Baptist minister who preached at different times in 1855.

Though the town immediately flourished, these were troubled times in Kansas, especially in towns and counties along the eastern border. Kansas had only recently been opened up for settlement, and various factions rushed to Kansas to support their cause — Slave State or Free State. In 1855, a fraternal organization called the Danites was founded by Mormon members. Tinsmith Patrick Laughlin joined the society which believed in the Free-State cause. However, he soon became disillusioned and openly proclaimed all of the society’s secrets. For this, the Danites vowed vengeance, and Samuel Collins, the sawmill owner, swore vengeance on Laughlin.

On November 29, when Laughlin was crossing the street, he was met by Collins, who attempted to shoot him, but his weapon misfired. Collins then drew a knife and stabbed Laughlin so severely that it brought him to his knees, but before he could proceed further, a friend of Laughlin’s, named Lynch, stepped from the sidewalk and fired on Collins. Although mortally wounded, Collins clubbed his gun and struck his assailant a terrible blow on the head, felling him to the ground. Collins was then picked up by his friends and died a short time later. Laughlin and Lynch, although both badly hurt, recovered. This was the end of the Danites in Doniphan.

In 1856, Thomas J. Key established the Constitutionalist newspaper as a mouthpiece for promoting slavery. The first school was taught by Mrs. D. Frank in a log cabin that summer.

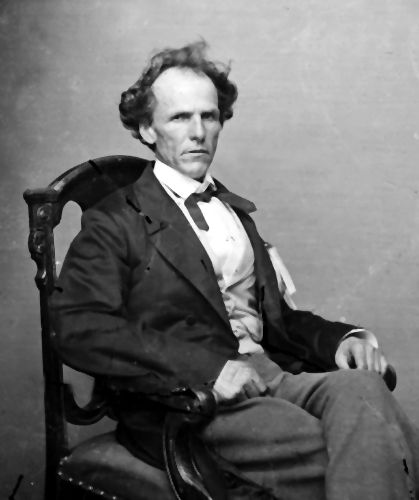

In 1857, James H. Lane, a prominent Free State political leader, was made the president of the Doniphan Town Company and moved to the town. He soon acquired a large part of the townsite, known as “Lane’s Addition,” and due to his influence, the government land office was located in Doniphan that year, bringing more prominence to the town.

In April 1857, James F. Forman purchased a sawmill valued at $2,500 and set it up on the bank of the river near the Collins mill. Forman also built a flouring mill near Spring Creek for $1,300. The 40-room St Charles Hotel was also built in 1857. Several church organizations were established early on, and some small frame structures were built in the town around this time, including St. John’s Catholic Church, perched atop the river bluffs. At this time, Doniphan had become an important political and commercial center and was called home to about 1,000 people, while nearby Atchison had only 200 residents.

By 1858, pro-slavery principles were becoming unpopular in Kansas, and the Constitutionalist newspaper was discontinued. It was soon replaced by the Crusader of Freedom, a Free State newspaper. However, this newspaper was short-lived.

Political rivalry caused the removal of the Government Land Office from Doniphan to Kickapoo in 1859, which saw the beginning of the town’s decline. However, glowing reports still resounded regarding the town. In James Redpath’s Handbook to Kansas Territory, published in 1859, he presented an optimistic view, stating:

“Doniphan, it is admitted by everyone, has the best rock-bound landing and the best townsite on the Missouri River anywhere above St. Louis. It has running through it a fine stream of water, which, by a trifling outlay that will soon be expanded, can be made to flow through five of the principal streets. A wealthy company has been chartered for the construction of a railroad for St. Joseph, through Doniphan, for Topeka, connecting the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. The stock is subscribed — ten percent paid in. That part of it from St. Joseph to Doniphan will be completed as soon as the connection is made with Hannibal. Lots can be purchased at Doniphan on more liberal terms than at any other town on the Missouri. We say to the emigrant, come to Doniphan, believing as we do that it is destined to be the great emporium of the upper Missouri. The population is about one thousand.”

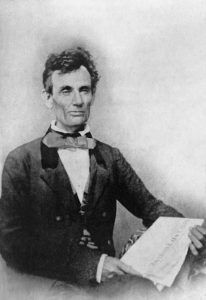

In 1859, James H. Lane moved to Leavenworth, and later that year, in December, aspiring presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln believed Doniphan to be significant enough to visit. He spoke to the townspeople and stayed in the area for eight days campaigning. During this year, Forman’s Flouring Mill was destroyed by fire, and a new mill of about the same capacity was erected and put in operation.

In 1860, the St. Charles Hotel, built in 1857, was destroyed by fire, and the following year, when the Civil War began, Doniphan’s population declined sharply. The Doniphan Post newspaper began the same year but lasted only one year.

In 1861, Forman’s Flouring Mill burned again, and afterward, James Forman retired from this branch of business, and it was never rebuilt.

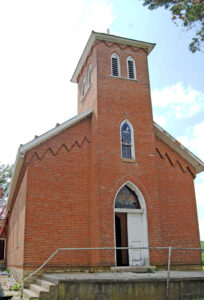

Doniphan’s population recovered after the Civil War, and several brick buildings were erected, including a large warehouse. In 1865, the Catholic Church and residence burned down, and two years later, the new St. John the Baptist Catholic Church was constructed from brick on land donated by Adam Brenner, known for his expansive vineyards and wine operation. The new brick structure measured 26 x 50 feet and included a stately bell tower with a fine-toned bell weighing nearly half a ton. A cross-gable wing measuring 24×36 was added around 1868. The church never had a residing full-time priest but was provided visiting priests from the Benedictine Abbey in Atchison. Today, the brick church is one of the few significant structures in Doniphan.

In 1867, Adam Brenner built an elevator with a capacity of 40,000 bushels for $16,000. In the fall of 1868, the Doniphan House Hotel was burned to the ground after many proprietor changes.

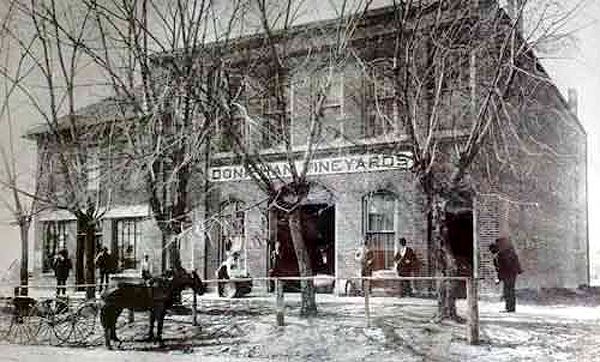

In 1869, George Brenner planted the first five acres of the famous Belleview vineyard. The same year, he erected a large two-story brick building to accommodate his wine interests. The building measured 65×44 feet, with a large cellar and a storage room for 90,000 gallons of wine. The Brenner vineyards would eventually occupy over 50 acres and employ dozens of workers for every harvest and year-round staff. The wineries produced as much as 150,000 gallons in their peak years, shipping to buyers nationwide.

The same year, Doniphan was incorporated, judges were appointed, and a city council was organized.

With the railroad’s arrival in northeast Kansas in 1870, the importance of the steamboat diminished, and the advantages of Doniphan’s excellent steamboat landing began to fade. The Atchison & Nebraska Railroad arrived at Doniphan in January 1871. At that time, there were 228 families in Doniphan, with a population of 1,020. That year, the Doniphan Democrat newspaper was launched in May and ran for about a year. Afterward, it was taken over by new owners, published briefly as the Doniphan Herald in the summer of 1872, and then discontinued.

In 1872, a fire burned Adam Brenner’s large grain elevator, its contents, and a large amount of grain. However, the vineyards were still doing well, as attested to by the Doniphan Herald, which stated:

“We visited the wine cellars of the Brenners this week, and to say that we enjoyed the sparkling fluid from the 1,000-gallon cask would not half express our delight in that visit. Such delicious wines are not found elsewhere in the United States. Those Brenner wines are getting a reputation not to be excelled anywhere in the country. Hermann [Missouri] has heretofore claimed the laurel in wines, but Doniphan now so far surpasses her in quality that Hermann must stand aside.”

In 1873, a brick schoolhouse was built by James F. Forman at a cost to the town of $8,000. This two-story structure measured 65×38 feet and contained four classrooms and a basement. In 1883, it had about 60 students.

By 1882, Doniphan had three general stores, two drug stores, a wagon shop, two blacksmith shops, a wholesale liquor house, a meat market, a hotel, a feed stable, three millinery and dressmaking establishments, two saloons, a printing office, four wine cellars, and a shoe shop. Professionals in town included two physicians, three carpenters, three stonemasons, a plasterer, a cooper, and a surveyor. There were three church organizations and two secret societies. The Atchison & Nebraska Railroad entered the town from the north, terminating between Sixth and Seventh Streets. This year, the town’s last newspaper, the Doniphan County Weekly News, began in March but lasted less than six months.

By 1887, the railroad no longer entered Doniphan. Instead, it bypassed it to the west and only stopped at Doniphan Station, a few miles northwest of town. This bypass undoubtedly harmed the towns’ businesses. By this time, nearby Atchison, Kansas, and St. Joseph, Missouri, flourished as railroad hubs, drawing many people and businesses away from Doniphan.

In June 1891, the Missouri River flooded, and a new southern channel was created, resulting in thousands of yards of railroad tracks washing away and leaving Doniphan landlocked. The steamboats once docked became an inland village beside a large pool of water called Doniphan Lake. The railroad rebuilt two miles to the west, and Doniphan went into a steep decline.

By 1905, Doniphan had only a few businesses left, including a blacksmith, two general merchandise stores, and a grocery store. By 1910, the population was only 134, and the following year, the Kansas City Star described the town as “desolate and almost deserted.” The Brenner family winemaking enterprises finally ended in 1912.

However, the town continued for several decades. Its post office closed its doors forever in August 1943, and its Rural High School Number 10 closed in 1947. In 1949, Doniphan still had a grocery store and a gas station but only about 50 residents. The Army Corps of Engineers emptied Doniphan Lake in the 1950s.

Today, little is left of Doniphan, except for a few buildings in various states of decay. However, its Catholic Church has been restored and utilized for special masses such as weddings and funerals. The Brenner Vineyards Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005, which includes 4.9 acres, the St. John’s Catholic Church, a two-story winery building, a barn, corncrib and pump-house, a smokehouse, and the ruins of Adam Brenner’s house and winery. A still-utilized cemetery sits nearby. A few residents still live in the area.

To reach Doniphan from Atchison, take River Front Road north from Riverfront Park and follow it to Mineral Point Road for about seven miles. The historic district is located at Mineral Point and 95th Roads.

© Kathy Alexander, Legends of America, updated March 2024

Also See:

Kansas Ghost Towns Photo Gallery

Quest for Treasure in the Missouri River

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas Cyclopedia, Standard Publishing, 1912

Brenner Vineyards Historic District Nomination

Cutler, William G.; History of the State of Kansas, A. T. Andreas, 1883

Gray, Patrick L. Doniphan County history, Roycroft Press, 1905

Lost Kansas Communities