The Chippewa, also known as the Ojibway, Ojibwe, and Anishinaabe, are one of the largest and most powerful nations in North America, having nearly 150 different bands throughout their original homeland in the northern United States — primarily Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan; and southern Canada — especially Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

Ojibway means “to roast till puckered up,” referring to the puckered seam on their moccasins. Formerly, the tribe ranged along the shores of both Lakes Huron and Superior, extending across the Minnesota Turtle Mountains and into North Dakota. Although strong in numbers and occupying an extensive territory, the Chippewa were never prominent in history, owing to their remoteness from the frontier during the colonial wars. According to tradition, they are part of an Algonquian group that included the Ottawa and Potawatomi, which separated into divisions when it reached Mackinaw, Michigan, during its westward movement. The Ojibwe language is a branch of the Algonquian language family.

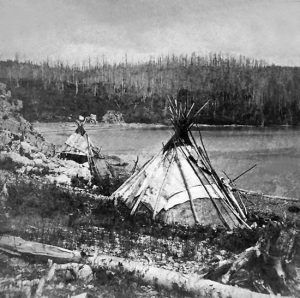

The Ojibwe lived in groups, and most, except for the Great Plains bands, led sedentary lives, with men engaging in fishing and hunting to supplement women’s cultivation of numerous varieties of corn and squash and the harvesting of wild rice. Their typical dwelling was the wigwam, built as either a domed or pointed lodge, made of bark or grass mats and willow saplings.

Early on, the Ojibwe were known for their birch bark canoes, birch bark scrolls, copper mining and trade, and cultivation of wild rice and Maple syrup. Their Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed, complex scrolls containing events, oral history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.

Traditionally, the Ojibwe had a patrilineal system in which children were considered born to the father’s clan. For this reason, children with French or English fathers were considered outside the clan and Ojibwe society unless adopted by an Ojibwe male. There is abundant evidence that polygamy was common amongst the tribe.

Some Chippewa bands, including those who lived at La Pointe Island, Wisconsin, were said to have practiced cannibalism, while other bands looked upon them with horror. The Pillager band in Minnesota also occasionally practiced cannibalism ceremonially.

Their creation myth is similar to that of the northern Algonquian, and, like most other tribes, they believe that a mysterious power dwells in all objects, animate and inanimate. These objects are called manitus, which are ever wakeful and quick to hear everything in the summer, but in the winter, they are in a sleep-like state after snowfalls. The Chippewa regard dreams as revelations, and some objects that appear in dreams are often chosen as a spiritual guardian. The Midewiwin, or grand medicine society, was formerly a powerful organization among the Chippewa that controlled the movements of the tribe and was a formidable obstacle to the introduction of Christianity.

When a Chippewa died, it was customary to place the body in a grave facing west, often in a sitting posture, or to scoop a shallow cavity in the earth and deposit the body therein on its back or side, covering it with earth to form a small mound, over which boards, poles, or birch bark were placed. However, this was not always the case, as the Chippewa of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, practiced scaffold burial with the corpse enclosed in a box. Mourning for a lost relative continued for a year unless shortened by the medicine society or by specific exploits in war.

Some historians had asserted that they were settled in a large village at La Pointe, Wisconsin, when America was discovered. However, in the early 17th century, they abandoned this area, many returning to their homeland in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan. In contrast, others settled at the west end of Lake Superior, where they were found by Father Claude Jean Allouez, a Jesuit missionary and French explorer, in 1865.

Sault Saint Marie appears to have been their headquarters in about 1640, as the earliest documentation of them is mentioned by Jean Nicolet de Belleborne, a French-Canadian woodsman, who called them Baouichtigouin, meaning “people of the Sault.” In 1642, they were visited by missionaries Charles Raymbaut and Isaac Jogues, who found them at the Sault and at war with a people to the west, probably the Sioux.

Because of their remoteness from the frontier, the Chippewa took little part in the early colonial wars. While the southern division of the tribe was known to be of a warlike disposition, those to the north of Lake Superior were considered mild and peaceable, so much so that their southern brethren termed them “the rabbits.” In the north, the members of the tribe were described as the “men of the thick woods” and the “swamp people,” terms that designated the nature of the country they inhabited.

The Marameg, a tribe closely related to, if not an actual division of, the Chippewa, who dwelt along the north shore of the lake, were incorporated with the latter at the Sault before 1670. On the north, the Chippewa were so closely connected with the Cree and Muskegon that the three could only be distinguished by those intimately acquainted with their dialects and customs. At the same time, on the south, the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi formed a sort of loose confederacy, frequently designated as the Three Fires.

The Chippewa people living south of Lake Superior in the late 1600s relied primarily on fishing, hunting, and cultivating maize and wild rice. Their possession of wild rice fields was one of the chief causes of their wars with the Dakota, Fox, and other nations. At about this same time, they came into possession of firearms and were pushing their way westward, alternately at peace, at war with the Sioux, and in almost constant conflict with the Fox tribe. The French reestablished a trading post at Shaugawaumikong (now La Pointe, Wisconsin) in 1692, which became a critical Chippewa settlement. At the beginning of the 18th century, the Chippewa succeeded in driving the Fox, already reduced by war with the French, from northern Wisconsin, compelling them to take refuge with the Sac.

They then turned against the Sioux, driving them across the Mississippi River and south to the Minnesota River. They continued their westward march across Minnesota and North Dakota until they occupied the headwaters of the Red River and established their westernmost band in the Turtle Mountains. It was not until after 1736 that they obtained a foothold west of Lake Superior. While the main divisions of the tribe were thus extending their possessions in the west, others overran the peninsula between Lake Huron and Lake Erie, which the Iroquois had long claimed. The Iroquois were forced to withdraw, and the Chippewa bands occupied the entire region, most of whom later became known as the Mississauga. In 1764, they were estimated to number about 25,000 people.

The Chippewa took part with the other tribes of the northwest in all the wars against the frontier settlements to the close of the War of 1812. Those living within the United States made a treaty with the Government in 1815 and afterward remained peaceful, residing on reservations or allotted lands within their original territory in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota.

Henry Schoolcraft, an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist who was personally acquainted with the Chippewa and married a woman of the tribe, described the Chippewa warriors as equaling, in physical appearance, the best-formed of the northwest Indians, with the possible exception of the Fox. Their long and successful contest with the Sioux and Fox tribes exhibited their bravery and determination, yet they were uniformly friendly in their relations with the French. They were also friendly with later European settlers. Still, any missionary efforts to convert them to Christianity had little effect, owing mainly to the conservatism of the native medicine men.

The Ojibwe fought in several wars and battles after European contact. These included:

- The Beaver Wars (1640 – 1701) – Also called the French and Iroquois Wars, this conflict was fought by the Iroquois Confederacy against the French and their Indian allies, including the Ojibwe.

- King William’s War (1688-1699) – The Ojibwe fought with the French against the English.

- Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713) – The tribe fought with the French against the English.

- The First French Fox War (1712–1716) – The Ojibwe joined the French to fight against the Fox tribe.

- Dakota Uprising (1862) – When the Dakota Sioux rose against the French, the Ojibwe fought with their French allies.

- King George’s War (1744 – 1748) – The tribe fought with the French against the English.

- French Indian War (1754 – 1763) – The Seven Years’ War was the fourth and final series of conflicts in the French and Indian Wars fought between the British and the French. Native Indian allies aided both sides. The war ended in a British victory, resulting in the end of the colony of New France (Canada).

- Pontiac’s War (1763–1766) – Native American tribes, including the Ojibwe, resisted British settlement of the Great Lakes region.

- Peoria War – The Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi form the “Three Fires Confederacy and force the Peoria tribe from the Illinois River.

- American Revolution (1775–1783) – the Ojibwe fought against the British and their colonies.

- Northwest Indian War (1785–1795) – Also called the Ohio War and Turtle’s War, numerous tribes, including the Ojibwe, fought against the United States for control of the Northwest Territory. The Treaty of Greenville ended the war, and the tribes were forced to cede much of present-day Ohio and Indiana to the United States.

- Tecumseh’s War (1811–1813) – The Ojibwe join the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh in an attempt to reclaim their Indian lands.

As a result of many of these wars, the Ojibwa ceded or sold land rights in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin to the federal government through several treaties, including one signed in 1854 that established permanent Ojibwa reservations in those three states.

Today, the Chippewa, or Ojibwe, are among the largest Native American Peoples on the North American continent. There are communities in both Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the second-largest First Nations population, surpassed only by the Cree. In the United States, they have the fifth-largest population among Native American tribes, surpassed only by the Navajo, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Lakota-Dakota-Nakota Sioux.

There are numerous recognized Chippewa tribes in Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, and Canada. The most recent is the Little Shell of Montana, which gained state recognition in the late 1900s and federal recognition in December 2019.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

A Chippewa Indian Man.

Also See:

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

Hodge, Frederick Webb, The Handbook of American Indians, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1906

Warpaths 2 Peacepipes

Wikipedia