Henry Plummer.

One of the most colorful characters of the Wild West, Henry Plummer, allegedly played both sides of the law during his short 27 years. Though he was thought to have been guilty of numerous crimes and rightly hanged in Bannack, Montana, for more than a century, today’s historians question whether or not he was truly guilty of the crimes he was accused of.

Born in Addison, Maine, in 1832, to William Jeremiah and Elizabeth Handy Plummer, he was the youngest of seven children. His father, older brother, and brother-in-law were all sea captains, and Henry was expected to follow in their footsteps. However, the young man was slight of build and consumptive, making the rigors of the sea trade too much for him to handle.

When Henry was a teenager, his father died, and the family began to struggle financially. Just two years after the California Gold Rush began, Henry promised his widowed mother that he could help the family by making his fortune in the West.

In April 1852, 19-year-old Henry sailed from New York on a mail ship to Aspinwall, Panama, traveled by mule train to Panama City, then boarded another ship for the rest of his journey to California. Twenty-four days after his departure, he arrived in San Francisco. Gaining a job at a bakery, Plummer soon earned enough money to move on to the mining camps of Nevada County, about 150 miles north of San Francisco.

A year after he arrived in California, documents show he owned a ranch and a mine outside Nevada City. He traded some of his mining shares for the Empire Bakery in Nevada City about 12 months later. By 1856, the residents, so impressed by the young man, persuaded him to run for sheriff. At the age of 24, he became marshal of the third-largest settlement in California.

The young marshal was well-liked by the citizens of Nevada City and respected for his promptness and boldness in carrying out his duties. He easily won the re-election in 1857. But, shortly after the election, he killed his first man. At the time, Henry was said to be having an affair with the wife of a miner named John Vedder, and when the angry husband confronted him, the two competed in a duel, for which Henry won.

Plummer was arrested and tried in a sensational, emotionally-charged case that went twice to the California Supreme Court before he was finally convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to ten years in California’s infamous San Quentin Prison. He began to serve his sentence on February 22, 1859, and residents quickly petitioned the Governor for a pardon, claiming that Henry had acted in self-defense.

Cyrus Skinner, among his comrades behind bars, serving time for grand larceny, would later be connected with Plummer again. Plummer served only until August 16, 1859, when he was released due to his tuberculosis and pressure from the petition to the Governor.

After his release, Henry returned to Nevada City, to the bakery, and became an avid customer of the many brothels in the settlement.

Before long, he was penniless and soon joined a group of bandits intent upon robbing area stagecoaches. The stage driver got away with his passengers and cargo in one such incident, but Plummer was arrested. Standing trial for the attempted robbery, the former sheriff caught a reprieve when he was acquitted due to lack of evidence.

But trouble had begun to follow Plummer around, and soon he was caught up in a brawl over a “painted lady” with a man named William Riley. When Henry shot the man on October 27, 1861, he was arrested again. This time, he escaped prison by bribing a jailer before he could be tried and fled to Oregon.

Along the way, he met another bandit named Jim Mayfield, who had allegedly killed the sheriff of a neighboring town.

Both were wanted men, and the ex-sheriff sent word to California newspapers that he and Mayfield had been hanged in Washington. It had the desired effect, curtailing the need for the desperadoes to look over their shoulders for the pursuing posse constantly.

In January 1862, Plummer landed in Lewiston, Idaho, with a woman companion, registered at the Luna House. Working in a casino, he soon ran into his old cellmate, Cyrus Skinner, and other individuals destined for the gallows in Montana, such as Club Foot George Lane and Bill Bunton.

Forming a gang, the like-minded men began to rob the local families of the area mining camps and primarily targeted the gold shipments traveling the roads from the mines. Somewhere along the line, Plummer abandoned his mistress, a woman with three children who had to resort to prostitution to feed herself and her family. He finally died an alcoholic in one of the seedier brothels in town.

Plummer began to roam the area between Elk City, Florence, and Lewiston. In Orofino, Idaho, he killed a saloon keeper named Patrick Ford. When the saloonkeeper kicked Plummer and some of his friends out of the saloon, Ford followed them to the stable, where he fired upon them. Plummer returned fire and killed Ford. When some of Ford’s friends began to form a lynch mob, Plummer hightailed it out of there and headed east to Montana.

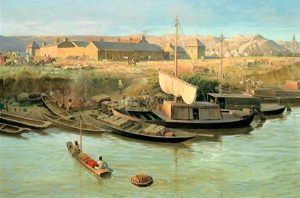

By September 1862, Plummer began to feel the effects of his tuberculosis and wanted to return home. Heading from Idaho across the Bitterroot Mountains, he traveled to Fort Benton, intending to go back east. Unfortunately, the upper Missouri River at Fort Benton was frozen, and the river was closed to Riverboat traffic. Planning to hold over for the winter, Henry went to work as a ranch hand at the Sun River Farm, a government ranch and Indian Agency, in October.

Plummer soon became enamored with Indian Agent James Vail’s beautiful sister-in-law, Electa Bryan. Henry and Electa spent about two months together and were quickly engaged to be married.

A former cohort of Plummer’s, Jack Cleveland, was also vying for Electa’s attention, which incensed Henry. Nevertheless, both men headed to Bannack, Montana, the most recent site of gold rush fever, in January 1863.

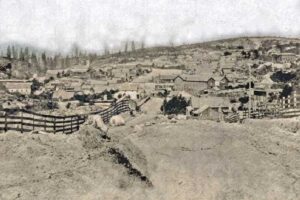

Hastily built to accommodate the many miners flooding the area, Bannack was called home to all manner of transient men, including Civil War deserters from both sides, river pirates, professional gamblers, outlaws, and villains. Lawlessness ran rampant as holdups occurred daily, and killings were just as frequent.

Henry soon rounded up another gang, calling themselves the Innocents, and began to relieve the gold-laden travelers from the Montana camps of their valuables. The Innocents grew quickly and became so large that secret handshakes and code words were instituted so one “Innocent” could recognize another.

One night, while Henry was drinking in Bannack’s Goodrich Saloon, Jack Cleveland, his old nemesis, began to taunt him by referencing Plummer’s outlaw activities. When Henry warned him to stop, Cleveland kept spouting his accusations, and Plummer fired a warning shot. Cleveland then pulled his six-gun, but Henry was faster, and soon Cleveland lay on the floor, mortally wounded.

Not yet dead, Cleveland was taken to the home of a butcher named Hank Crawford, two doors down from the saloon. Crawford heard Cleveland’s last words as he continued to extol the tale of Plummer’s deceit and corruption. Three hours later, Cleveland was dead, and Plummer was arrested. However, Plummer received yet another reprieve when he was acquitted based on witness testimony that Cleveland had threatened him.

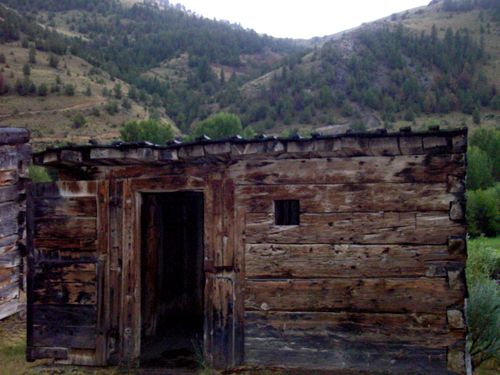

Bannack, Montana Jail by Kathy Alexander.

By late spring 1863, more than 10,000 men were hunting for gold along Grasshopper Creek, and the lawlessness in Bannack had reached epidemic proportions. The frightened citizens of the settlement decided that the outlaws had to be stopped and advertised for a sheriff. Two men, vowing to corral the outlaws, stepped up to the plate — Plummer and a butcher named Hank Crawford.

Plummer lost the election to the popular butcher, an event that fired his reckless temper, and he went after the new sheriff with a shotgun. However, a friend warned Crawford, who shot Plummer in his right arm, temporarily ruining his gunfighting abilities. Undaunted, Plummer immediately practiced shooting with his left hand until his accuracy was just as deadly. When Hank Crawford caught wind of this, he turned in his badge and left Bannack, never to return.

In the new election for sheriff, Plummer became the leading lawman on May 24, 1863. Plummer quickly appointed two of his henchmen, Buck Stinson and Ned Ray, as deputies. Unknown to the people of Bannack, Plummer’s group of Innocents had now reached over 100. Having the opposite desired effect for the citizens of Bannack, crime in the town increased dramatically after Plummer was elected. In the next few months, more than 100 citizens were murdered.

On June 20, 1863, Henry and Electa were married and soon settled into their log home in Bannack. However, Electa did not stay long. Less than three months later, she left for her parents’ home in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. She would never see Henry again.

The Innocents stepped up their efforts to rob the gold-laden travelers from the Montana camps and helped the Sheriff punish the “villains” of the community on a gallows that Plummer had erected. However, the few hanged on it by Plummer and his men were not members of the Innocents. The Innocents were well organized and said to have killed anyone who might witness their crimes, most of which were quickly covered up. Blatant killings went unpunished. Residents who suspected anything feared for their lives and kept their mouths closed. The ambitious sheriff soon extended his operations to Virginia City when he was appointed Deputy U.S. Marshal for the region of Idaho Territory east of the mountains in August 1863.

By December 1863, the citizens of Bannack and Virginia City had had enough. Men from Bannack, Virginia City, and nearby Nevada City met secretly and organized the Montana Vigilantes. Masked men began to visit suspected outlaws in the middle of the night, issuing warnings and tacking up posters featuring skull-and-crossbones or the “mystic” numbers “3-7-77.” While the meaning of these numbers remains elusive, the Montana State Highway patrolmen wear the emblem “3-7-77” on their shoulder patches today. Interesting.

The vigilantes dispensed rough justice by hanging about twenty-four men. When one such man, Erastus “Red” Yager, who was about to be hanged, pointed the finger at Henry Plummer as the gang leader, all hell broke loose.

The residents were divided over whether Henry was part of the murderous gang. But one night, after heavy drinking in a local saloon, the vigilantes decided that Henry was guilty and tracked him down. On January 10, 1864, fifty to seventy-five men gathered up Plummer and his two principal deputies, Buck Stinson and Ned Ray. The three were marched to those very same gallows that Plummer had built. Ned Ray was the first hanged, followed by Buck Stinson–both men spewing epithets every step of the way. According to one legend, Plummer promised to tell the vigilantes where $100,000 of gold was buried if they would let him live. However, the vigilantes ignored this as they gradually hoisted him up by the neck.

After the execution, armed guards stood by the gallows for about an hour. The three bodies were left hanging until the following day. Plummer’s was the only body placed in a wooden coffin, and none were buried in the cemetery; instead, all three were buried in shallow graves in Hangman’s Gulch about a hundred yards up from the gallows.

The vigilantes went on to hang the rest of the Road Agents that they could locate in such locations as Hellgate (Missoula), Cottonwood (Deer Lodge), Fort Owen, and Virginia City.

Vulnerable to vandalism, legend has it that the grave was broken into twice. The first time, allegedly by the local doctor, who, out of curiosity, severed the right arm from the body to search for the bullet that had hit Plummer when he went after Hank Crawford. Reportedly, the doctor found the bullet “worn smooth and polished by the bones turning upon it.” The second time it was broken into was reportedly by two men around the turn of the century who decided to dig up the grave after spending several hours in a local bar. To prove they had done it, they severed the head and carried it back to the Bank Exchange Saloon, where it remained on the back bar for several years until the building burned, along with all its contents. Yet another legend states that the skull found its way into the hands of an unnamed doctor who sent the specimen back east to a scientific institution to try to figure out why Plummer was so evil.

Electa learned of her husband’s death in a letter, and she always maintained that he was innocent. In fact, over the past several decades, many historians, researchers, and authors have questioned whether the tale of Henry Plummer was told correctly.

Many believe that the whole thing is all a fraud, a story fabricated to cover up the real lawlessness in the Montana Territory – the vigilantes themselves. Many of the early stories on which the outlaw tale is based were written by the editor of the Virginia City Newspaper, who was a member of the vigilantes himself.

Further testimony to support the theory is that the robberies did not cease after the twenty-one men were hanged in January and February 1864. In fact, after the “Plummer Gang” hangings, the stage robberies showed more evidence of organized criminal activity, more robbers involved in the holdups, and more intelligence passed to the actual robbers.

Having taken control, the vigilantes were ruthless. On one such occasion, in attempting to get the names of the road agents, they looped a noose around the neck of a suspect named “Long John” Franck and repeatedly hoisted him until the poor man gasped out the answers the vigilantes wanted to hear. They did the same to Erastus “Red” Yager, who pointed the finger at Henry Plummer as the gang’s leader.

Further, the vigilantes brooked no criticism of their methods. When a preacher’s son named Bill Hunter expressed his outrage by shouting on a mining camp street that pro-vigilantes were “stranglers,” his frozen corpse was found three weeks later dangling from the limb of a cottonwood tree.

There is little evidence connecting Plummer with any crime committed in the Bannack area other than the “confession” of a criminal attempting to save his own life. Plummer’s activities as an outlaw band leader in Lewiston have also been disputed, as evidence was found that he was living in California.

Three years after Plummer was killed, the vigilantes virtually ruled the mining districts. Finally, leading citizens of Montana, including Territorial Governor Thomas Meagher, began to speak out against the ruthless group.

In March 1867, the miners issued their own warning that if the vigilantes hanged any more people, the “law-abiding citizens” would retaliate “five for one.” Though a few more lynchings occurred, it was clear that the era of the vigilantes had passed.

As for what happened to Electa, she ultimately moved to Vermillion, South Dakota, where she married James Maxwell, a widower with two daughters. Electa and James had two sons of their own, Vernon and Clarence. Electa lived until May 5, 1912, and was buried at Wakonda, South Dakota.

The historical town of Bannack, Montana, was placed under the protection of the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks in 1954 and is now known as Bannack State Park.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

Bannack, Montana – Gold to Ghosts

Ghost Town Ghost in Bannack, Montana

Henry Plummer by Emerson Hough

See Sources.