John Willard was one of the first to speak out against the Salem witchcraft madness, which would cost him his life.

Little is known about John’s early life, but he grew up in Lancaster before moving to Groton, Massachusetts. There is some evidence that he may have been related to Major Simon Willard, one of the most prominent Massachusetts land speculators, town founders, and politicians of the time. Major Willard was known to have had a business in Lancaster and to have founded the town of Groton, and John Willard was associated, in his land dealings in both communities, with Simon Willard’s sons. However, this relationship with Simon Willard has not yet been confirmed.

John married Margaret Wilkins of Salem Village in the 1680s, and the couple was thought to have first lived in Groton. However, they were soon in Salem Village and would eventually have three children. Margaret was a third-generation member of the large, tight-knit Wilkins family, which was highly wary of outsiders. As such, John Willard was not a welcome member of the clan. Headed by patriarch Bray Wilkins, the family included Bray’s seven children and numerous grandchildren who lived on and near “Will’s Hill” in the extreme western part of Salem Village.

Years earlier, Bray Wilkins and his sons had made a foray into what they hoped would be a profitable commercial venture. Though they continued farming, they also ventured into the logging industry. Ultimately, the business failed, and the Wilkins nearly lost their land. This embittered them against powerful and wealthy merchants in general. When Salem Village made strides to separate from Salem Towne, the Wilkins family was second only to the Putnam family in pushing for the division. By the 1680s, Bray and his sons had returned entirely to the role of subsistence farmers on marginal land, and though they were not impoverished, their hopes and dreams of being affluent were a distant memory. They believed that only the land itself had proven trustworthy, and the survival of Salem Village as a stable agricultural community should be the focus of the residents. The push to separate Salem Village from Salem Towne had, over the years, divided the settlement. Those who made their living in commercial businesses prospered with their ties to the larger community, while the farmers saw no need to continue their ties to the larger city. This division in Salem Village had festered and grown so severe that by the 1680s, neighbors were pitted against neighbors, and sometimes families against their own.

It was into this quarrelsome, bitter environment of the village and the economically marginal Wilkins family that John Willard married. Making matters worse, Margaret Wilkins was the first in her family to marry someone who was not from Salem Village. Already wary of the “outsider,” the Wilkins family’s uneasiness increased when it became known that John Willard was interested in land speculation.

In March 1690, he and three partners purchased a large tract of some 400-500 acres north of Salem Village. Within a few months, two substantial tracts of land were sold to “outsiders” at a profit to the partnership. At this point, the Wilkins family turned against John Willard.

When the witch hysteria began in Salem Village in early 1692, the accusations were coming in fast and furious. As a result, Constable John Putnam, Jr. tried to employ John Willard to help him arrest some of the accused. However, John Willard not only refused to assist in bringing in people he believed to be innocent, but he also made the mistake of speaking out against the validity of the trials and the accusers. About the “afflicted girls,” he is said to have spoken out against the proceedings with the words, “Hang them. They are all witches.”

Within no time, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr. would say that the apparition of John Willard was afflicting her. She testified that he first appeared to her on April 23, 1692, grievously tormenting her. When Willard heard of the accusation, he went to Thomas Putnam, Jr’s house and denied the allegations. For several days, Ann Putnam, Jr. said no more but would soon be claiming that the apparition of her infant sister, Sarah, who had died, was appearing to her, crying out for vengeance against John Willard.

Willard soon sought the counsel of his 81-year-old grandfather-in-law, Bray Wilkins, knowing of his friendship with the Putnams. Genuinely mystified by the intensity of feeling against him, he told the elderly Bray Wilkins that he was “greatly troubled” and asked Bray to pray with him. However, pleading a prior engagement, Wilkins put him off. Early in May, Margaret Willard’s cousin, Daniel Wilkins, the grandson of Bray Wilkins, became ill. The 17-year-old Daniel, Mercy Lewis’s beau, died of his mysterious affliction within a week. Unfortunately, a coroner’s jury found evidence that Daniel had died an unnatural death. At about the same time, the elderly patriarch of the family, Bray Wilkins, was struck by a painful and alarming urinary difficulty. Both afflictions were blamed on John Willard, and accusations quickly increased. Before long, Ann Carr Putnam, Sr., accused Willard of having murdered no fewer than thirteen Salem Villagers during his brief residence in the community.

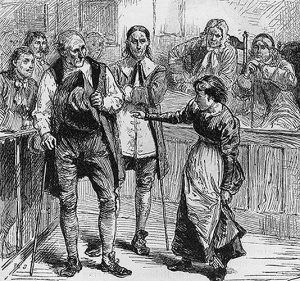

A complaint was soon sworn against John Willard by Thomas Fuller, Jr., and Benjamin Wilkins, Sr., accusing Willard of having afflicted Daniel Wilkins and Bray Wilkins. A warrant was issued for his arrest on May 11, 1692, but when Constable John Putnam, Jr., went to arrest him, Willard was nowhere to be found. Several days later, on May 17, however, Willard was located in Lancaster, arrested, and brought back to Salem Village for examination. Throughout the interrogation and trial, Willard maintained his innocence, stating, “I am as innocent as the child unborn.”

During the legal process, several of the “afflicted girls” and Wilkins family members were often present. The finger of witchcraft was pointed at him by no fewer than ten members of the Wilkins family. “Witness” was given by Susanna Sheldon and Mary Warren in the form of terrible fits. Ann Carr Putnam, Sr., claimed that she had seen many ghosts who told her Willard had killed them; Mercy Lewis and Mary Walcott testified that they had seen the apparition of John Willard afflicting Daniel Wilkins, pressing and choking him until he died. Sarah Bibber would say she had seen John Willard’s specter hurt Mary Walcott and Mercy Lewis before turning on Bibber herself.

Margaret Wilkins Knight would tell the court that Willard had previously beaten his wife. Samuel Wilkins testified that he had repeatedly been irritated and afflicted by something in a dark-colored coat — and that it was John Willard. John Wilkins would blame the death of his wife, after having delivered a baby, on John Willard. And, patriarch, Bray Wilkins, would say that he came down with his illness after John Willard had looked at him with an evil eye. Other “witches” who had already confessed to witchcraft, including Richard Carrier, Margaret Jacobs, and Sarah Churchwell, also accused Willard of witchcraft.

With all this evidence, it is no surprise that John Willard was found guilty of witchcraft on August 5. At 37, he was hanged on August 19, 1692, along with John Proctor, George Burroughs, George Jacobs, Sr., and Martha Carrier. John Willard maintained his innocence until the very end.

If John Willard were guilty of beating his wife, that would tarnish any “hero” status. But his actions in refusing to arrest innocent people, speaking out against the madness, and his unwillingness to compromise his integrity to save his own life certainly make him an honorable man in the otherwise dishonorable witch hysteria in Salem Village.

One member of the Wilkins family did not join in the accusations against John Willard-Thomas Wilkins. Thomas would later emerge as one of the four “dissenting brethren” who led the anti-Parris movement from within the church. When the elderly Bray Wilkins died, the executor of his estate was none other than the evil Thomas Putnam, Jr. Thomas Wilkins was disinherited.

John’s wife, Margaret Wilkins Willard, would later remarry William Towne, and the couple would have several children.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

Procedures, Courts & Aftermath

Timeline of the Witchcraft Hysteria

See Sources.