“…They seemed to be very sincere, upright, and sensible of their circumstances on all accounts; especially John Proctor and John Willard, whose whole management of themselves, from the jail to the gallows, and whilst at the gallows, was very affecting and melting to the hearts of some considerable spectators, whom I could mention to you — but, they are executed, and so I leave them…”

— Thomas Brattle in a letter written after the hanging of August 19, 1692

John Proctor (1631-1692) – John Proctor was born on October 9, 1631, to John and Martha Hopper Proctor in Assignton, Suffolk County, England. In 1635, he immigrated to the United States with his parents when he was three years old, along with his one-year-old sister Mary. John Proctor, Sr. bought a farm in Ipswich, was considered a prosperous landowner, and occupied various offices of trust in the colony. When John Proctor, Sr. died, he left his estate to his son. In about 1655, John married Martha Giddons, and the couple lived in Ipswich. They would have four children, but the first three would not survive beyond childhood. Just a few days after the birth of their fourth child, Benjamin Proctor, Martha died from complications of childbirth. Proctor would then marry Elizabeth Thorndike in December 1662, and the couple would have seven children, some of whom would not make it to adulthood.

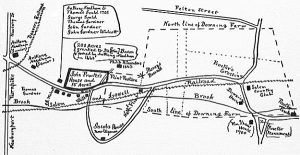

In 1666. John purchased the Downing Farm on the outskirts of Salem Town, in what is now known as Peabody. He also leased one of the largest farms in the area. Called “Groton,” the 700-acre spread was situated southeast of the Salem Village line. Two years later, he established a tavern on Ipswich Road in Salem. Though it may seem odd in Puritan New England, having been granted a license for a tavern was a sign of prestige. His wife and older children then managed the tavern, while he and his oldest son, Benjamin, managed the rest of his properties. John’s second wife, Elizabeth Thorndike Proctor, became ill shortly after the birth of their son, Thorndike, on July 15, 1672. She died on August 30, 1672

John married his third wife, Elizabeth Bassett, on April 1, 1674, a woman 20 years his junior. The couple would eventually have six children. Like his previous wife, Elizabeth Bassett Proctor and the older children of his previous marriage would watch after the tavern while John spent his days working on the farm. The successful farmer and entrepreneur had never been involved in Salem Village politics, nor was he involved in any litigation or disputes with the powerful Putnam family, who was behind many accusations. However, his interests were diametrically opposed to those of the old, established Salem Village elite, and he was an “outsider.” And, by some accounts, he was said to have been a part of the “Anti-Parris Network” led by Israel Porter, a major enemy of the Putmans.

When his father died, Proctor inherited a portion of an estate worth £1200, adding to his already successful enterprises. Though he had become fairly wealthy, he was not fully accepted or respected by the townspeople of Salem Village. He was often called “Goodman,” a title similar to “Mr.” but usually used to signify someone of a lesser social rank. Described as an enormous man, very large framed, impulsive, and with great force and energy, he was very outspoken.

In March 1692, things began to unravel for the Proctors. After an arrest warrant was issued for Rebecca Towne Nurse, an elderly respected member of Salem Village, on March 23, 1692, John Proctor was enraged, saying: “If the afflicted girls” were let alone, so we should all be devils and witches.” Rebecca was related by marriage to John Proctor. Though some residents agreed with John Proctor, doubting whether the “afflicted girls” should be believed, they wouldn’t say anything, for fear that they might be accused and convicted themselves. However, this didn’t stop the outspoken Proctor, who was the first to speak out, voicing his opinion of the possessed state of the girls, their accusations, and standing up heartily against the trials. It would be a fatal mistake.

At about the same time, a servant of the Proctors, Mary Warren, began to have fits, saying that she was “seeing” the specter of Giles Corey. Dismissive of her claims, he simply made Mary work harder and threatened to beat her if she had any more fits. Mary did not report any more sightings for some time, but then she started to have fits again in his absence. Unfortunately, John Proctor made the mistake of telling Samuel Sibley early in the morning of March 25, 1692, that Mary Warren was having fits and that he would “thresh the Devil out of her.” He further remarked that the afflicted persons “should rather be had to the Whipping post.”

Talking to Sibley was not a good idea, as he was Mary Walcott’s uncle and surely repeated the story of John Proctor’s skepticism about the afflictions. In the meantime, Mary Warren was kept hard at work at the Proctor home and told that she would not be rescued if she ran into fire or water during one of her fits. After her “fits” stopped, she posted a note at the Meeting House to request prayers of thanks. That very night, Mary said that Elizabeth Proctor’s spirit woke her to torment her about posting the note. On April 3, 1692, Samuel Parris read Mary’s note to the church members, who began questioning Mary after the Sunday services.

In the meantime, Mercy Lewis and Abigail Williams also made accusations against Elizabeth Proctor. On April 8, 1692, a complaint was filed by Captain Jonathan Walcott and Lieutenant Nathaniel Ingersoll, both of Salem Village, which accused Elizabeth of committing witchcraft upon Abigail Williams, John Indian, Mary Walcott, Ann Putnam, Jr., and Marcy Lewis. She was examined, indicted, and sent to jail on April 11. During her examination, her husband John defended her and said that the girls were hallucinating and the information they gave was false. As a result, the “afflicted girls” also accused him, and he, too, was sent to jail. Later that month, 31 men from Ipswich, Massachusetts, filed a petition attesting to the upstanding character of John and Elizabeth Proctor, denying that they had ever seen anything that would indicate they were witches. The following month, another petition was filed on behalf of the Proctors, which included 20 signatures of men and women, some of which were from some of the wealthiest landowners of Topsfield and Salem Village. This petition questioned spectral evidence and testified to the Christian lives that John and Elizabeth had led.

On July 23, 1692, fearing that they could not get a fair trial in Salem Village, John Proctor, along with other accused and imprisoned “witches,” wrote a letter to the Reverend Increase Mather, James Allen, Joshua Moody, Samuel Willard, and John Bayley, the clergy of Boston, who were known to be uneasy with the witchcraft proceedings. The letter described torture used to elicit confessions and pleaded with the ministers to intervene, asking them to move the trials to Boston or have new judges appointed. The clergy would respond by meeting at Cambridge on August 1, 1692, eventually concluding that they needed to take action to stop the Salem madness. However, it would not be soon enough for John Proctor.

On August 2, 1692, the court met in Salem to discuss the fate of John and Elizabeth Proctor and several others. At some point during this time, John wrote his will, but he did not include his wife, Elizabeth. Though the reason he did not include her is unknown, many historians believe that he assumed she would be executed along with him.

On August 5, 1692, John and Elizabeth Proctor were tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hung by the neck until dead. On August 19, 1692, John Proctor was hanged on Gallows Hill in Salem, along with George Burroughs, George Jacobs Sr., John Willard, and Martha Carrier. John pleaded at his execution for a little respite of time, claiming he was not fit to die. His plea was, of course, unsuccessful. Elizabeth, however, would not immediately be hanged because she was pregnant. She would give birth to a son she named John, after his deceased father, on January 27, 1693. By this time, the witch hysteria had died down and her execution wasn’t followed through. Elizabeth and John Proctor III remained in jail until May 1693, when Massachusetts Governor William Phips ordered a general release that freed all prisoners who remained in jail.