Out of sorrow and chagrin, out of dread,

was born a new love for the land which

had been desecrated, but, somehow

also consecrated, in the blood of innocents.

Salem Village, now part of Danvers, Massachusetts, is a historic district encompassing a collection of properties from the early settlers.

The village, located about 5-7 miles north of Salem Towne’s meeting house, grew and developed its own identity and separate interests in the early years of settlement.

In 1623 a group of colonists attempted to set up a fishing establishment at Cape Ann on the North Shore of Massachusetts. Though the project failed, a few men, led by Roger Conant, refused to give up and, in 1626, settled in Naumkeag, later renamed Salem, in 1629. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was issued a charter by the monarch of England in 1629, giving them the rights of autonomy and self-rule. The colonists were intent on establishing a commonwealth where the Puritan Church could exist without the interference of the Church of England. Ministers arrived in 1629, and the settlers began organizing a church. Around 1630, settlers converted an existing Naumkeag Indian trail into the Old Ipswich Road, connecting Salem and Boston’s main cities.

However, the land in Salem Towne was not fertile, so many settlers moved outside the “city,” and numerous small communities emerged, including Salem Village, Beverly, Andover, Topsfield, Wenham, and many others. The land where Salem Village was situated was once controlled by the Naumkeag branch of the Massachusett tribe. The village was permanently settled in 1636.

In the 1630s, the communities grew as more and more people immigrated to the area due to the repressive government of King Charles I in England. At about the same time, the Pequot Indian War erupted from 1634-1638.

By 1640 Salem would be the second most important colonial town next to Boston, but the high rate of immigration began to slow. This was because the Puritans were in power in England, and the persecution had ended. At that time, the colony became more self-sufficient and claimed sovereignty. In the 1650s, the colonies prospered. In Salem and other areas, the church became the most prominent organization.

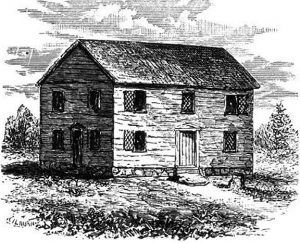

Salem Village, located about five miles north of Salem Towne, was also growing and developing its own identity and separate interests. In 1666 Salem Village petitioned for a separate church but was denied. However, the farmers continued requesting due to the distance from town. Finally, Salem Village was granted the right to build its own church and hire a minister in 1672. However, the villagers would remain members of the Salem Towne Church, which would govern the smaller church. The village was also permitted to establish a committee of five, to assess and gather taxes from the villagers – including church members and non-church members, for the ministry. Though villagers continued to participate in Salem Towne’s life, voted in Salem Towne elections, and paid most Salem Towne taxes, for the first time, they had a degree of autonomy.

The village members immediately began to build the Salem Village Meeting House and search for a minister. While the church was under the guidelines of the larger Salem Towne Church, the ministers were not ordained and, as a result, could not administer communion or admit candidates to formal church membership. From the beginning, there was conflict between those in Salem Towne who opposed the building of a separate church and those in Salem Village regarding the choice of a minister. Over the next several years, the dissension would divide the community, making enemies of friends and family members. Though this was not unusual in many New England communities, many historians believe Salem Village had more conflict than was typical. During the 1670s-80s, the new church’s first three ministers would all step down, unsatisfied with the position, the church, and the village itself.

The first minister, Reverend James Bayley, arrived in Salem Village in October 1672. An inexperienced pastor, just three years out of Harvard, Bayley walked into conflict. From the beginning, some village members felt Bayley was hired “upon the invitation of a few.” Like other fledgling communities, the procedures for hiring were informal and irregular.

Even though there were dissenters, things went well initially, and in June 1673, Bayley was invited to remain in his post. Five farmers donated 40 acres of land to him, and the minister began to build a house. However, that same year, 14 villagers fell into arrears on their taxes for church support, officially designating the discontent of some church members.

The central issue was actually who had the authority to call or dismiss a minister in Salem Village, making it a highly political conflict. Because the village was not an “official” town, the only authority in the village was the church, which angered many villagers who attended other churches in nearby communities. The tissue mushroomed to such proportions that it was taken to the county courts, the Salem Towne Church, and even the Colonial Legislature. Though the Salem Church advised the dissidents to submit to Bayley’s continued ministry “without any further trouble,” the conflict continued.

By 1679, a minority of the village, led by Nathaniel Putman and Bray Wilkins, had turned fully against Bayley, accusing him of neglecting his church duties and omitting family prayers in his own household. With the Village deeply divided over the legitimacy of his call, Bayley finally gave up the fight and left Salem Village in 1680. He would then minister for a few more years in Killingworth, Connecticut, before giving up the profession and becoming a doctor in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

Unfortunately, his departure did little to ease the dissension in the village. However, the village inhabitants, both church members and non-members, selected a committee headed by Nathaniel Putman to look for a new minister.

The second minister, George Burroughs, who had graduated from Harvard in 1670, arrived in Salem Village in 1680. As one of his conditions for coming, Burroughs had stipulated “that in case any difference should arise in time to come, that we engage on both sides to submit to counsel for a peaceable issue.” Though this was the common language in 17th century New England, it undoubtedly had more significance for Burroughs, who had probably learned something of what confronted him from Bayley.

The differences were not long in arising, and Burroughs found himself amid the conflict taking place in the village. Some villagers accused him of being abusive to his wife. It was to Burroughs that Jeremiah Watts wrote his letter of April 1682, lamenting the disputes of Salem Village, saying, “Brother is against brother, and neighbors are against neighbors, all quarreling and smiting one another.” With many villagers not paying their taxes, Burroughs was not always being paid and borrowed money from the Putnam family.

By early 1683, the minister’s salary was not being paid at all, and in March, Burroughs stopped meeting his congregations. The Reverend Burroughs accepted an offer to resume his ministerial duties at Casco Bay, which had been reorganized. He stayed there until the community was once again destroyed by Indians in 1690. He then moved to Wells, Maine.

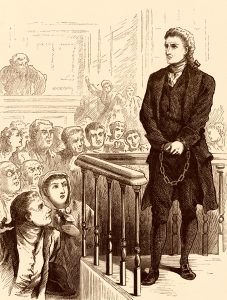

Unfortunately, his brief time in Salem Village would come back to haunt him. In May 1692, during the Salem witch trials, based on the accusation of the Putnams, who had sued him for the previous debt, Burroughs was charged with witchcraft, arrested, and brought back to Salem. He was executed on August 19, 1692.

Deodat Larson, an unordained minister, followed Burroughs. Reverend Deodat Lawson came from Boston and was pastor from 1684 to 1688. Again contention arose in the church, and Larson’s bid to become an ordained minister failed. Like his two predecessors, Lawson ran into problems with Salem villagers, and the Salem Village Church was being torn apart by two groups, each wanting control of the pulpit. This resulted in much of the congregation rejoining the First Church in Salem. In 1688, Lawson left Salem Village after his contractual obligation period. He then became a pasture in Scituate, Massachusetts, before abruptly returning to England, where he lived for the rest of his life.

The villagers continued to hope that the formation of their own church, apart from the Church of Salem, would somehow transcend the chronic divisions that plagued the community. As a result, they began to search for an ordained minister. It soon came to their attention that Reverend Samuel Parris, who was guest-preaching at several Boston area churches, sent him an invitation in the spring of 1689. A Harvard Divinity School dropout, Parris first attempted to follow his father’s profession as a West Indies merchant, but when that failed, he returned to Massachusetts to become a minister.

On June 18, 1689, at a general meeting of all villagers, it was agreed to hire Samuel Parris at an annual salary of £66, and the villagers would provide firewood for both the church and parsonage. At a later meeting, the villagers agreed they would also provide Parris and his heirs the village parsonage, barn, and two acres of land.

It was a fateful decision that Parris did not enter into lightly. He was aware of the conflicts in the village that had taken place in the last several years. However, with his Puritan beliefs that each person was responsible for monitoring his neighbor’s piety, he knew that conflict was inevitable. On November 19, 1689, the Salem Village church charter was finally signed, and Reverend Samuel Parris became Salem Village’s first ordained minister. Salem Village now had a true church. To the parsonage, Reverend Parris brought his wife, Elizabeth, his nine-year-old daughter Elizabeth, his 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams, and a slave couple he had brought from the West Indies, John and Tituba Indian.

His ministry began smoothly, but as Parris began to reveal his beliefs and traits, several Salem Villagers, including a few church members, did not like what they saw. A serious, dedicated minister, he combined his evangelical enthusiasm to revitalize religion in Salem Village with psychological rigidity and theological conservatism.

While the Salem Towne Church and most Puritan churches of the time were relaxing their standards for church membership, Parris held rigid to traditional strict standards, which required that members be baptized and make a public declaration of experiencing God’s free grace to become full members. Most village church members were happy with Parris’s traditionalism, which elevated their status by sharply distinguishing them from non-church members. But, a minority dissented and found allies among non-members, constituting a large and influential part of the Salem Village community.

Suddenly, Parris also found himself in the midst of contract disputes with the members of the Salem Village Church council. The council alleged that the contract, which was seemingly never formalized, only provided Parris with the parsonage and lands only so long as he remained the minister, rather than Parris’ beliefs that the contract granted Parris outright ownership of the house and lands. At the same time, Parris was making plans to refurbish the meeting house commensurate with its new status as a full church. But, to many, this signaled a church both more intrusive and more expensive than some villagers wished.

By the fall of 1691, only two years after his ordination, Parris’s ritual orthodoxy, overbearing disposition, and the disputed contract had caused the village and church to once again break into factions. Church attendance fell, and village officials refused to provide firewood to warm the church or Parris’ house. Matters turned worse when a new Committee of Five was chosen by the village in October 1691, which announced its refusal to relinquish the ministry house and land to Parris or to collect taxes for his salary, leaving it to the villagers to pay by “voluntary contributions.” Parris then called upon church members to make a formal complaint to the County Court against the committee’s neglect of the church. The factional fighting also began to play out in his weekly sermons as a battle between God and Satan.

This was the backdrop for the Salem witchcraft accusations, which would begin right in Reverend Parris’ own home.

At the time that the witch trials began, the population of Salem Village is estimated to have been between 500 and 600 residents. Though most of the accused in the Salem witch trials lived in nearby Salem Village, now known as Danvers, others lived in the nearby villages of Beverly, Middleton, Topsfield, Wenham, and others. Although no one knows for certain why the Salem Witch hysteria began, some historians point to economic factors, while others insist on religious and psychological pressures.

By the end of May 1692, more than 150 “witches” had been jailed. As the hysteria spread, accused and imprisoned “witches,” afraid for their lives, began to confess to witchcraft. By September, 19 people had refused to confess and were hanged, including 71-year-old Rebecca Nurse. Cooler heads eventually prevailed in early 1693, and the court began disallowing “spectral evidence,” bringing an end to the witch hysteria.

Salem Village eventually petitioned the Crown for a charter as a town. According to legend, the King denied the charter. However, on June 9, 1757, the town was incorporated anyway and named for the Danvers Osborn family. At the time of the American Revolution, Danvers was a shipping and shipbuilding center where tidal mills prospered. Its local bricks became nationally famous, while the later leather tanning industry brought a diverse and colorful mixture of new immigrant labor to the area. Tapleyville emerged in the 1830s as a center for the production of woven carpets, where English and Scottish weavers settled and made their homes. Danvers Plains took advantage of important crossroads and the introduction of the railroad in the 1840s to become a prominent commercial center. Putnamville and Danvers Highlands were noted for their important and early shoe manufacturing industry, while farms throughout Danvers became known far and wide for the Danvers half-long carrot and the Danvers onion, which is still popular today.

Today, the Salem Village Historic District in Danvers contains over a dozen houses in Danvers dating from that era, many associated with the witchcraft tragedy of 1692. Many of these buildings are located along Centre Street. The house of one of the convicted “witches,” Rebecca Nurse, still stands in Danvers and can be visited as a historical landmark. Now operated as a museum, the Nurse Homestead is located at 149 Pine St. in Danvers. The foundations of the 1692 Parsonage, Nathaniel Ingersoll’s Ordinary, the Sarah Osborne House, Joseph Putnam’s home, and Bridget Bishop House can also be seen.

Today, Danvers supports a population of about 26,500 and continues to retain much of the hominess and architectural heritage of old New England.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2023.

Also See: