Elizabeth Booth

Sarah Churchill

Elizabeth Hubbard

Mercy Lewis

Elizabeth Parris

Ann Putnam, Jr.

Susanna Sheldon

Mary Warren

Mary Walcott

Abigail Williams

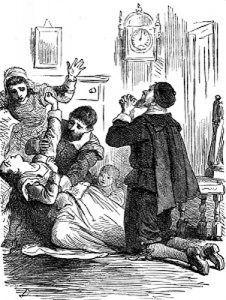

In the cold winter of 1691-92, the colonists of Salem Village, Massachusetts, were at war with the Indians, the weather was harsh, and the villagers relied on the Church for some sense of safety. During this time, two little girls — Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, the daughter, and niece of Salem Village Minister Samuel Parris, began the practice of fortune-telling, even though it was regarded as a demonic activity in the Puritan community. Soon thereafter, Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams became strangely ill, having fits, spouting gibberish, and contorting their bodies into odd positions. The Reverend Samuel Parris was sure that prayer could cure their odd behavior, but his efforts were ineffective.

He soon brought in the local doctor William Griggs, who could find no physical cause for the girls’ problems and diagnosed them as being afflicted by the “Evil Hand,” commonly known as witchcraft. Other ministers were consulted, who agreed that the only cause could be witchcraft, and since the sufferers were believed to be the victims of a crime, the community set out to find the perpetrators.

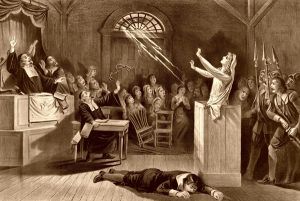

Within no time, three witches were accused — Tituba, Reverend Parris’ slave; Sarah Good, an impoverished homeless woman; and Sarah Osborne, who had defied conventional Puritan society. As the witch hysteria spread, numerous other young women claimed to be afflicted.

But what was the original cause of these so-called “fits”? Modern technology suggests they may have been caused by some combination of stress, asthma, guilt, boredom, child abuse, epilepsy, and delusional psychosis.

Another theory was first presented in a 1976 article in Science magazine where Dr. Linnda R. Caporael, a Professor in the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, argued that a disease called “convulsive ergotism” might have been to blame. The disease is brought on by ingesting rye grain infected with ergot, a fungus that can invade developing kernels of rye grain, especially under warm and damp conditions.

In 1691, during the rye harvest in Salem, these conditions existed. Furthermore, one of the Puritans’ main staples of their diet was cereal and bread made of harvested rye. Convulsive ergotism causes violent fits, a crawling sensation on the skin, vomiting, choking, and hallucinations. In fact, the hallucinogenic drug LSD is a derivative of ergot. Many of the symptoms of convulsive ergotism seem to match those attributed to Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams.

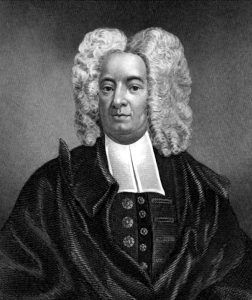

There is another theory that might explain the girls’ symptoms. In 1689, Cotton Mather, minister of the Old North Church in Boston, published a bestselling book called Memorable Providences. Relating to Witchcraft and Possession, the book detailed an episode of supposed witchcraft a year earlier involving an Irish washerwoman named Goody Glover. Mather’s account, describing the symptoms of witchcraft, was widely read and discussed throughout Puritan New England and just happened to be in the meager library of Reverend Samuel Parris. Interestingly Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams’ behavior mirrored those described in Cotton Mather’s book. With their interest in fortune-telling, might these young girls have taken it further and read the book?

But what of the many others also exhibited similar afflictions throughout the year? Rye might still be the culprit, but mass hysteria might also be attributed. Mass hysteria, also called collective hysteria and group hysteria is the spontaneous manifestation of the same or similar hysterical physical symptoms by more than one person. Mass hysteria typically begins when an individual becomes ill or hysterical during a period of stress, and others begin to manifest similar symptoms. Unfortunately, scientists have found a clear preponderance of female victims over the years.

Stress was certainly present in 1692 Salem. The community was at war with the Indians; the people strongly believed that Satan was present on earth and very active, many watched as their friends and family were arrested and hanged, and a large proportion of the “afflicted” were orphans or completely alone. With little hope for the future and no monetary or emotional support from direct family members, there would be few men interested in them, and their marriage prospects looked especially grim. Further, some researchers have suggested that their dramatic performances gained the respect and attention of the community, which helped them deal with the oppression they felt within Puritan society.

From June through September of 1692, nineteen men and women, all having been convicted of witchcraft, were hanged in Salem Village, and another man was pressed to death under heavy stones for refusing to make a plea. Hundreds of others faced accusations of witchcraft; dozens languished in jail for months without trials until the hysteria that swept through Puritan Massachusetts subsided.

In May 1693, a general release freed all prisoners who remained jailed. By the end of the trials, 24 villagers had died. Within five years, Salem officials publicly apologized for their fervor at a “Day of Fast and Repentance.”

The Afflicted:

Elizabeth Booth (1674-??) – One of the “afflicted girls,” Elizabeth Booth was the daughter of George and Elizabeth Booth of Salem Village. On June 8, 1692, the 18-year-old Elizabeth allegedly showed signs of affliction by witchcraft. Her afflictions were supported by her mother and younger 14-year-old sister Alice. Though she participated in examinations, inquests, and trials, she was not a favorite of the authorities, and her name was chosen for use on only a couple of complaints. However, she did do her share of damage. She testified that ghosts had come to her and accused John and Elizabeth Proctor of serial murder, stating that they had killed at least four people. She also made accusations against Wilmot Redd and Giles Corey. Just 19 days after the executions on September 22, 1692, Elizabeth Booth, apparently free of any afflictions, married Jonathan Pease and started her own family. In the meantime, Wilmot Redd, John Proctor, and Giles Corey had been put to death, and Elizabeth Proctor was in prison, sentenced to death, but under a reprieve until her child was born.