The Tabor Triangle, involving Horace, Augusta, and Elizabeth McCourt Baby Doe Tabor, is a rags-to-riches story full of scandal and intrigue in the Rocky Mountains. Horace Tabor, a simple merchant, grubstaked several miners in Leadville, Colorado, and soon became wealthy and influential. He left his wife for a much younger woman — Baby Doe, resulting in a high scandal. Both Horace and Baby Doe died in poverty.

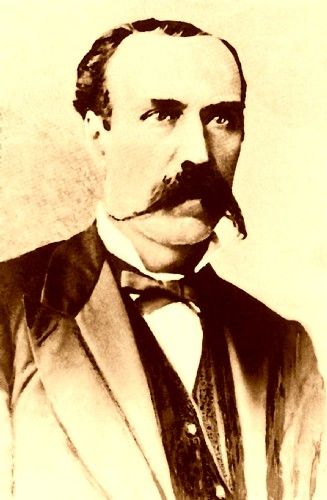

Horace and Augusta Tabor

Horace Tabor was born on April 6, 1830, in Holland, Vermont, to Cornelius Dunham Tabor and Sarah Ferrin. He had a sister and three brothers. When he was 19, he left home to work in the stone quarries of Massachusetts and Maine. William B. Pierce, who owned a quarry in Augusta, Maine, hired Horace and his brother, John, and would later become Horace’s father-in-law.

Augusta Pierce was one of seven daughters and three sons born to William B. Pierce and Lucy Eaton. Growing up in a comfortable middle-class home, she was a fragile child but also strong-willed. Horace and Augusta began a courtship that would eventually lead to marriage.

In 1855, Horace joined a group organized by the New England Emigrant Aid Society to populate the Kansas territory with anti-slave settlers. He moved to Kansas and homesteaded a piece of land on Deep Creek in Riley County, called “Tabor Valley,” to this day. His hard work and willingness to help the anti-slavery cause got him elected to the “Free Soil” legislature, which sat in defiance of the so-called legitimate territorial government during a violent period of civil unrest, which earned the territory the name of “Bleeding Kansas.”

Early in 1857, he returned to Maine to marry Augusta Pierce, then 24, and bring her back to Kansas. Rattlesnakes and Indians visited the area too often, and Augusta, appalled by the territory’s raw ruggedness and rough cabin, often fell to tears. However, they spent the next two years trying to make the farm productive until Horace heard stories of gold discoveries in the western part of the Kansas Territory (now Colorado).

In the spring of 1859, they left Deep Creek with their baby son Maxcy and two friends from Maine. Following the Republican River Trail, they walked across the barely explored landscape of northern Kansas and southern Nebraska until they reached Denver. While the men hunted for food, Augusta tried to keep the campfire alive, often with only buffalo chips, since there was no wood on the high plains. It took them six weeks to make a trip that could be made a decade later by train in under thirty hours. Just one month after their journey on the Republican River Trail, Horace Greeley took the same route, describing it as “the acme of barrenness and desolation.”

Though Horace initially tried prospecting in fields close to Denver, he decided to try his luck farther inland. In the spring of 1860, they headed to California Gulch, just south of Leadville. Their last journey across the high plains was easier than their trip to California Gulch.

Dragging loaded wagons over steep snow-bound mountain passes, they could sometimes see the remains of the campfire they made the night before. Augusta cleaned their clothes in icy streams, prepared meals from the barest of rations, and cared for baby Maxcy during the journey. She almost died while crossing a river when the wagon bed rose from the swift running water and started taking her and the baby downstream. Catching a tight hold of some branches bought her enough time for the men to come to the rescue, after which she collapsed unconscious.

Their arrival in the gold camp at California Gulch made Augusta, the first woman known to venture into those parts, curious. She endeared herself to the miners by becoming the camp’s cook, laundress, postmistress, and banker, using the gold scales she and Horace had brought to weigh the “dust.”

That first summer in the mountains earned them enough money to return to Kansas to buy more land and spend the winter in Maine. In the spring of 1861, they returned to Colorado, where they began following a succession of mining camps as they appeared, flourished, and then disappeared.

Traveling from one mining camp to another on the eastern slope of the Continental Divide, they prospected at Payne’s Bar (now Idaho Springs), Oro City 1, California Gulch, Buckskin Joe, and Oro City 2. At each mining camp, she and Horace became the camp’s provisioners, a pattern they would repeat at other times in the next twenty years. Their travels took them twice over the great Mosquito Range and eventually to the place just outside California Gulch, which was to become Leadville.

Typically, Augusta would board and bake for the miners while Horace tried his luck at placer sluicing or other means of getting the precious minerals. He was mainly Augusta’s partner in keeping the store and running the post office and the bank for the various camps. Considered “sturdy merchants” by their neighbors, they were beloved for their honesty and Horace’s generosity.

However, Augusta was sure that his good nature was not only the source of other folks’ high regard for them but also how they would eventually become impoverished. Hers was the firm hand on the Tabor rudder. Though Horace always tended to give things away, Augusta saved, and by the late 1870s, just before Tabor “struck it rich,” they had amassed a comfortable net worth of about $40,000 — a considerable sum in those days. In November 1868, they settled down again in Oro City, located in the California Gulch, and reopened their store, where he was the postmaster.

In July 1877, Horace and Augusta built a house and moved to Leadville, where they ran a grocery and supply store. Horace, elected as Leadville’s first mayor, also served as postmaster. In the spring of 1878, while Tabor worked in the store, two German prospectors asked if he would grubstake a claim. It was not the first time that Tabor had grubstaked miners, and he provided them with $17.00 in provisions that first day and additional supplies on two more occasions for a total of $54.00. For the provisions, the miners promised Tabor a one-third interest in any ore produced by their finds. The German prospectors located a claim on Fryer Hill, named the Little Pittsburgh, and began digging a shaft.

On April 15, 1878, Tabor’s generosity hit pay dirt when the two miners, August Rische and George Hook, announced to Tabor that they had found silver in the Little Pittsburgh Mine. By July, nearly a hundred tons of ore had been taken from the mine, and each of the three partners had an income of $50,000 a month. In the fall, Hook sold out to Tabor and Rische for $98,000, and later, Rische sold his interest to Jerome Chaffee and David Moffat for over a quarter of a million dollars.

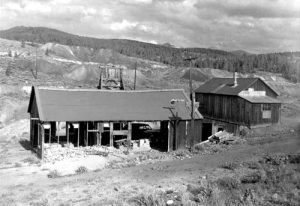

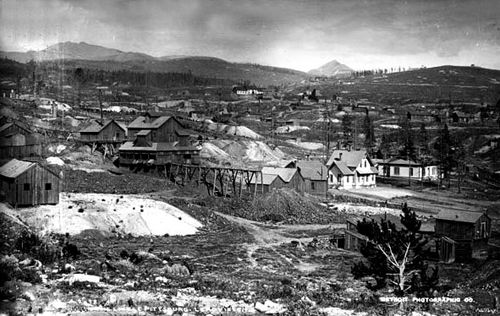

The Little Pittsburg Mine in 1882.

Tabor held on to his share and consolidated his claim with other partners on Fryer Hill. Horace quickly became the acknowledged leader of the silver mining community around Leadville. The consolidated group shared four million dollars before Horace sold his interest for one million. Horace went on to own partial stakes in several other successful mines, including the Chrysolite, which he bought with Marshall Fields of Chicago, the mine yielding 3 million dollars before Tabor sold his interest for 1 ½ million. In 1879, he purchased the Matchless Mine for $117,000, the first he owned entirely. For quite some time, no mine was its “match,” as it produced up to $2,000 daily in high-quality silver ore.

Continuing his generous spirit, Tabor provided Leadville with two newspapers, a bank, and a handsome opera house within the next two years. However, Augusta was not happy with “striking it rich,” and any differences between the two were exacerbated by the outrageous wealth Horace’s mines deposited in their lives. Though Augusta was no stranger to comfort, she could not deal with such immense, unlimited resources. Her warnings to save and spend carefully now seemed silly to Horace, who could not spend his money as fast as he accumulated it. After all the years of hardscrabble and toil, Horace, who was almost 50 years old, wanted to live it up. However, Augusta took no pleasure in their sudden riches, refusing to change her dress or behavior.

The Tabor Mansion in Denver, courtesy of Denver Public Library.

When Horace built a stately mansion in Denver, she refused to live upstairs in the master bedroom, instead preferring the servants’ quarters next to the kitchen. She kept a cow tethered to the front door, which she insisted on milking herself. Horace, who had been made the state’s Lieutenant Governor by then, was embarrassed. He wanted to live in style befitting his station, but Augusta only scoffed at such statements.

With all the tension at home, Tabor’s eyes began to stray. His newfound wealth and power brought him much attention, and he loved to spend money on beautiful women and lavish them with gifts. In a chance meeting at the old “Saddle Rock Cafe” in 1880, the “Silver King,” for which he was known by then, met the beautiful Elizabeth McCourt “Baby” Doe, and both of their lives would change forever.

Baby Doe Tabor made her mark on Colorado history as the bold girl from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, who ignored conventional Victorian attitudes of feminine modesty. How Baby Doe made her dreams come true may have irked Denver’s high society at the time, but today, she is celebrated as an individualist and a dreamer of the great American Dream.

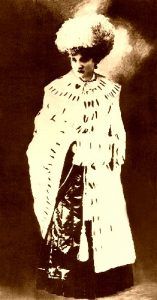

Baby Doe

“Baby” Doe was born Elizabeth Bonduel McCourt on October 7, 1854, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to Peter McCourt, Sr., and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Nellis. She was said to have been the prettiest of seven children and displayed a lively and independent spirit with a tomboy disposition and the face of a cherub. She was called “Lizzie” by her family, after her mother. In the winter of 1876, she won a Church figure skating contest, unheard of for a girl. The contest brought her to the attention of Harvey Doe, Jr., and the two began to court. Harvey’s mother highly disapproved of the relationship due to Lizzie’s being Catholic and “beneath” the Does economically. Despite her objections, the two continued to date and eventually became engaged. Harvey was the only son raised in an affluent family, where he had been coddled and spoiled by his mother and his four sisters. However, Lizzie thought he was a sweet man, and the two were married a short time later, in 1877. Harvey’s father owned a half interest in the Fourth of July Mine in Central City, and the young newlyweds set off on a new life of adventure. “We’ll go west and make our fortune overnight in gold. People do it all the time out there!” said Harvey.

In the rough and tumble mining community, Lizzie’s beauty and lively spirit brought her considerable attention from the primarily male mining population. Harvey, not accustomed to hard work, had difficulty making the mine profitable, eventually forcing Lizzie to don miners’ clothes and work alongside him. The unliberated settlement caused her to become the brunt of gossip and raise eyebrows. Gossip notwithstanding, she was still a favorite and was given the nickname “Baby” Doe – the miner’s sweetheart, which followed her for the rest of her life.

Meanwhile, Harvey fell into debt, their Fourth of July Mine paid less than hoped, and their three-year marriage faltered. Baby Doe was to find that Harvey was a poor provider, being both lazy and a procrastinator. Finally, Harvey was forced to take a job mucking in the Bobtail Tunnel, and they moved to Blackhawk, where the rent was cheaper. Lizzie was left home with little to occupy her time, no friends, and living in poverty.

Harvey worked night shifts and came home so exhausted that he did nothing but write long letters to his mother. The rift between the two widened into a chasm when Harvey lost his job and drifted from camp to camp, leaving Lizzie at home for long periods. With little to occupy her time, Lizzie took long walks, entertaining herself by looking longingly in the windows of the shops. Finally, she made a friend of Jacob Sandelowsky, a successful clothing merchant and part-owner of the Sandelowsky-Pelton store in Central City.

Jake Sands.

As he later changed his name, Jake Sands was handsome with dark curly hair, and the two were frequently seen together at the not-so-conservative Shoo-Fly Saloon during Harvey Doe’s absences. The Shoo-Fly was a dance hall and gambling establishment with rowdy miners looking to have a good time at the tables or the brothel, and Lizzie’s lively personality was a hit with the customers.

Harvey’s absences continued, and he began to drink heavily. Harvey’s female family often would provide him with money, but Lizzie rarely saw any of it. Unable to pay the rent, they were forced to move often. Then, late in 1878, Baby Doe became pregnant, and the times grew even more desperate when Harvey again deserted the home front during her critical time of need. Baby Doe later claimed she would have starved without her friend, Jake Sands. On July 13, 1879, Lizzie gave birth to a stillborn son, and Jake was there to help, making all the arrangements and paying her expenses. Many have speculated that Jake was the father of this baby, but the answer to that question will never be known.

The only clue left behind about the baby was a handwritten note found in Baby Doe’s scrapbook after her death. Dried flowers were placed around the handwritten words: “My baby boy, born July 13, 1879, had dark, dark hair, very curly, large blue eyes. He was lovely, Baby Doe.”

After the birth of her stillborn son, Jake readied a new store in Leadville and suggested that Baby Doe, having no reason to stay in Central City, might as well come along. Although she did pay a visit to Leadville at Jake’s request, she ended up returning to Central City to try one more time to reconcile with Harvey. However, nothing had changed between the two of them. Harvey was still weak, lazy, and jobless, and finally, his family had come to a point where they refused to give him any more money. Harvey’s hard drinking and lack of ambition did not match Baby Doe’s high aspirations, and finally, in 1880, Baby Doe sued for divorce on the grounds of “nonsupport” and moved to Leadville.

Jake Sands arranged for Baby Doe to stay at a boarding house and suggested they might consider marriage. Though Jake was Baby’s closest friend, she wasn’t in love with him, and within just a couple of months, any thoughts of a life with Jake quickly vanished when Baby Doe met Horace Tabor.

Horace and Baby Doe

Seemingly, it was love at first sight for both of them. Almost immediately, the two became sweethearts, and Horace moved Baby Doe into a suite at the Clarendon Hotel next to his Tabor Opera House in Leadville.

Although Horace was Lieutenant Governor and still married, the affair blossomed, and later, he put Baby Doe up at the elegant Windsor Hotel in Denver.

Over the next few years, Horace grew increasingly estranged from his wife Augusta as his affair with Baby Doe became public knowledge. Tabor once commented to Baby Doe, “You’re always so gay and laughing, and yet you’re so brave. Augusta is a damned brave woman, too, but she’s powerfully disagreeable about it.”

Eventually, Horace and Augusta parted, as much from his abstinence as from hers. Baby Doe was only the catalyst for a separation that left Horace and Augusta wanting, locked into their worlds by the stubbornness and individual gustiness that had sustained them through their earlier struggles, braving the frontier.

However, when Horace asked Augusta for a divorce, she refused. Not to be denied, Horace secretly engineered a divorce in Durango, Colorado, which was later found to be illegal. Whether Horace knew this or was simply defiant, he and Baby Doe were secretly married in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 30, 1882. When Augusta Tabor learned of the marriage, it was too late to contest it.

Augusta vigorously fought the legal divorce, which Horace continued to pursue relentlessly. She requested separate maintenance and claimed her husband was worth over $9 million. Tabor denied this, which was probably true, but more accurate estimates placed his worth at about three million.

After a long, drawn-out, and much-publicized battle, Augusta received the $100,000 a month income, the Denver mansion, and other properties, though it brought her little happiness. Augusta eventually moved to Pasadena, California, where she died on February 1, 1895, a wealthy, respected, and lonely woman, leaving her son Maxcy over 1.5 million dollars.

Meanwhile, Horace Tabor’s fame grew, and through political favors, he secured a 30-day appointment to Henry Teller’s vacated senatorial position in Washington, D.C., where he was sworn in on February 3, 1883. To wind up his short stint in Congress, Horace and Baby Doe were married again on March 1, 1883, in a lavish and scandalous public ceremony in Washington, D.C.

The invitations had real silver borders and silver-lettered letters. Baby’s wedding dress cost $7,000, and Horace gave her a $75,000 diamond necklace as a wedding gift. Horace’s congressional friends, including the President, attended the wedding, but their wives refused to attend the “disgraceful” event. The alleged divorce and marriage scandal raged on and became front-page news nationwide. It embarrassed Washington and other prominent figures in high social circles.

After marriage, they returned to Denver, where Horace bought Baby Doe a block-long mansion. Still, she quickly learned that not just anyone dripping with diamonds and furs could join Denver’s exclusive high society. The people of Denver spread horrible rumors and gossip about Baby Doe’s “shameless” and “scandalous” past in Central City.

Given the scandal of the divorce and their age differences, the wives of Denver’s wealthiest men refused to accept her as one of their own. However, despite the age difference and the social shuns, nothing could wilt their blossoming marriage, and they shared a loving home life for the next ten years.

A hundred peacocks strutted on the lawn outside the mansion, and the landscape was adorned with more controversial decorations, including some nude statues that further offended Baby’s highly proper female neighbors. In response, the highly spirited Baby Doe had her dressmaker make dresses for the statues. The two lived extravagantly, spending as much as $10,000 a week on lavish parties, traveling, and other luxuries.

At their height, the Tabors were one of the five wealthiest families in the country. During this time, they built the Tabor Grand Opera House in Denver and had two daughters, nicknamed Lillie, born July 13, 1884, and Silver Dollar, born December 17, 1889.

Tabor Grand Opera House in the 1920s.

Baby Doe’s fame lies mainly in her dazzling beauty. Admirers wrote poetry about her petal-soft complexion, lovely strawberry-blond curls, deep blue eyes, and sparkling personality. Baby Doe’s friends recognized her inner charms as well. Baby Doe made friends with many actors and actresses who played at the Grand Opera House and accepted her outgoing personality, finding her both lovely and admirable. This lessened the hurt she felt from Denver’s social elite, who thought she was shocking, showy, and scandalous. The wildly ambitious Baby Doe was hailed as the “Silver Queen of the West,” while Horace was touted as Denver’s “Grand Old Man.”

For Horace and Baby Doe, the years following their marriage were a constant whirlwind. The Tabor mines yielded millions of dollars in silver, especially the Chrysolite and Matchless Mines. The Matchless Mine alone produced over 9 million dollars. The Tabors continued to enjoy their expensive parties, distant travels, and lavish nights at the newly built Tabor Grand Opera House. In addition, campaigns for political office (not to mention jewelry, furs, and gowns of the finest silk and lace for Baby Doe and their two young daughters) occupied much of Tabor’s time and money. The Tabor fortune grew by the day and, being too vast to count, allowed the Tabors to spend extravagantly. The generous Horace Tabor opened his wallet for investments in more silver mines, new companies that needed capital, and some risky deals that did not land a dime in profits. The ten golden years between 1883 and 1893 were filled with endless possibilities for Horace and Baby Doe.

With Baby Doe on his arm, Horace Tabor’s plans to turn Denver into the “Paris of the West” seemed within reach. Baby Doe’s dreams matched her husband’s – an adventure of grand living and outstanding civic accomplishments. However, like all good things, it ended all too soon. The fairytale ended in 1893 when the country moved to the gold standard. Silver, Horace’s central holding, along with parcels of highly mortgaged property, came crashing down, along with the Tabors’ lifestyle. Horace, failing to listen to the advice of others and diversify, faced ruin. In the interim, and adding to the crisis, Tabor had also made several unsuccessful, if not unwise, investments in foreign mining ventures that failed. He lost vast amounts of money in Mexico and South America. However, regardless of the now destitute condition of the Tabors, Horace never lost faith in the future, and until his dying day, he always found work of some kind, hoping to recapture his lost wealth.

Baby Doe, Horace, and their young daughters Elizabeth “Lillie” and Rose Mary “Silver Dollar” moved out of their Capitol Hill mansion and into a rented cottage. At age 65, Horace shoveled slag from area mines at $3.00/day until he was finally appointed postmaster of Denver just a year before his death. Baby Doe remained optimistic about regaining Tabor’s lost fortune, but it never panned out.

Many people who disliked Baby Doe predicted she would divorce Tabor if he lost his fortune. However, Baby Doe was loyal and devoted to her husband until the end. In April 1899, Horace took ill with appendicitis, and a few days later, before his death, he was said to have told her…” Hang on to the Matchless Mine; if I die, Baby, it will make millions again when silver comes back.” However, this statement was later disputed as being made up by a writer who wanted to sell her books. Flags were lowered to half-mast in Colorado, and 10,000 people attended the funeral. Just 45 years old, Baby Doe would never again live a lavish lifestyle.

Still beautiful and relatively young, Baby Doe could easily have remarried. She chose, instead, to “hold on to the Matchless,” continuously seeking funds to “work” it. With her two children in tow, Baby returned to Leadville and took up residence in the one-room, 12 by 16-foot structure that initially served as a tool shed at the Matchless Mine. Her elder daughter, 15-year-old Lillie, so resented the place that she boldly stated that she was leaving, and borrowing the money for the train fare from her uncle, she went to Wisconsin to live with her grandmother, ceasing all contact with her mother and sister.

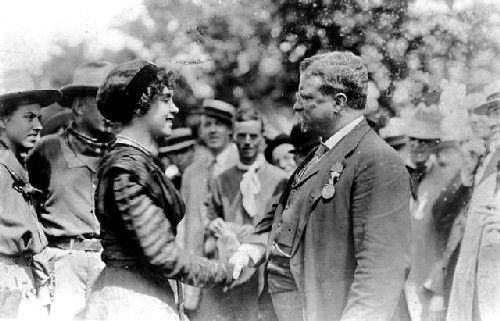

Silver Dollar Tabor

Silver Dollar, a 10-year-old tomboy, initially thrived on the adventure of living and working at the mine. She liked to write poetry, and Baby Doe encouraged this endeavor, helping her publish several songs. One of these included a song to celebrate Theodore Roosevelt’s visit to Leadville in 1908, “President Roosevelt’s Colorado Hunt,” the music of which was written by a friend in Denver.

The song was well-received in Colorado, and the Denver Post published a lengthy article about Silver Dollar’s “budding career.” In 1910, the song was sung for Mr. Roosevelt, and Silver Dollar met the man.

But, alas, the spirited girl began attending Leadville’s parties and drinking heavily. After a heavy night of partying, she became involved in a scandal with a local saloon keeper, and Baby Doe sent her to Denver, where she thought she would be better off.

Silver Dollar obtained a job at a local newspaper and wrote a western novel called The Star of Blood. But neither adventure was successful. Then she tried her hand at publishing a small periodical, but her life was spiraling downward, and after a couple of years, she decided to move to Chicago, Illinois. There, she planned to make one last stab at making a writing career, and if that proved unsuccessful, she told her mother she would join a convent.

Baby Doe never saw her again but received sporadic letters until an article appeared in the Denver paper, which outlined the details of Silver Dollar’s grizzly murder.

During her time in Chicago, Silver Dollar continued on a path of destruction, getting involved with drugs, continuing to drink, and joining a burlesque show for some time.

She lived with one after another ill-fitted man until one of them killed her by pouring scalding water over her naked body. Silver Dollar was 35. Baby Doe denied the entire story, stating that Silver Dollar was safely in a convent. Though she probably knew it was true, Baby Doe would never admit otherwise.

Baby Doe, who stayed at the cabin for her remaining 35 years, was a proud woman who routinely refused charity of any kind. Periodically, she would trudge into town for supplies, which she paid with chunks of “valuable” ore she picked up around the property, unaware that the sympathetic shopkeepers who accepted her samples as payment probably dumped the worthless rocks as soon as she left.

Contrary to popular belief, she did not “hold on to the Matchless as it will pay millions again,” as some have incorrectly reported, which were Horace Tabor’s deathbed words. The Matchless Mine had long since been lost to foreclosure and had failed to produce, even with several new attempts by the new owners. Baby Doe was living in the tiny cabin only due to the generosity of the current owners of the worthless mine, where she scribbled page after page of her increasingly paranoid and, ultimately, delirious thoughts.

As years passed, Baby Doe, with no income and unable to buy anything, would wrap her feet in burlap sacks held with twine. When sick, she would doctor herself with turpentine and lard. With the help of creditors and through the kindness of her Leadville neighbors, she was supplied with the bare necessities of life. However, food and clothing sent to this very proud woman were sent back unopened.

When a movie about Baby Doe Tabor came out in 1932, the promoters offered to pay her and her expenses if she attended the Denver premiere. She refused and would never see the movie because it was about her old life. A year later, a friend, who was a priest, and two lawyers tried to talk her into suing the movie producers for libel, promising her that she would receive $50,000. Again, she refused, stating that she didn’t need the money because the Matchless Mine was getting ready to provide her with more than that amount.

However, the movie did bring her publicity, which resulted in her receiving several sympathetic letters, often including money. She accepted this money, as it did not fall under her definition of “charity.”

Baby Doe at her cabin in October 1933, courtesy of Denver Public Library.

On February 20, 1935, Baby Doe struggled to get to town for a few supplies, and a grocery delivery man gave her a ride back from town, checking to ensure she had food, water, and wood. She wrote in one of her endless diaries: “Went down to Leadville from Matchless – the snow so terrible, I had to go down on my hands and knees and creep from my cabin door to 7th Street. Mr. Zaitz’s driver drove me to our get-off place and helped pull me to the cabin. I kept falling deep down through the snow every minute. God bless him.”

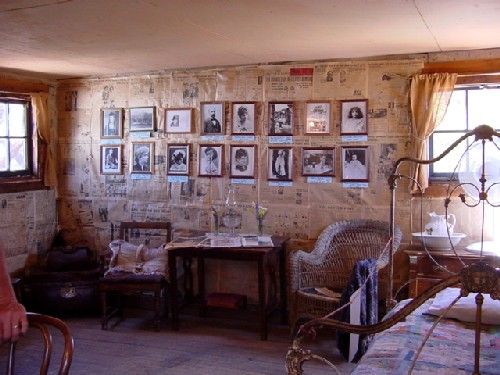

Baby Doe’s Cabin Interior after she died in 1935, courtesy Denver Public Library.

He was the last person to see her alive. The snowstorm continued to rage for several days before it finally cleared. Neighbors, who had routinely kept an eye on her, became alarmed when they didn’t see smoke curling up from her chimney. On March 7, 1935, they slogged through the 6-foot snow drifts and discovered the tiny 81-year-old woman dead and lying frozen on her cabin floor. Later, reports said she had suffered a heart attack.

Her body was sent to Denver and buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery beside her beloved husband, Horace. The cabin at the Matchless Mine, where she spent so many solitary years, was ransacked by souvenir hunters who made off with many of her things. Photographs of the cabin after her death depict a slovenly mess, but Baby Doe, though a bit of a pack-rat, was said to have neatened and tidied the mess created by those who invaded her home after her death. After her death, 17 iron trunks that had been placed in storage in Denver were opened, as well as several gunny sacks and four trunks left at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Leadville.

All that remained of the Tabor fortune were several bolts of unique, untouched, and quite exquisite cloth, several pieces of china, a tea service, and some jewelry, including a diamond and sapphire ring. The famous watch fob and chain given to her husband, Horace Tabor, at the opening of the $700,000 Tabor Opera House in Denver were also found, along with several memorabilia pieces.

Baby Doe’s Cabin, Kathy Alexander.

Baby Doe became a legend, the subject of two books and a Hollywood movie. Eventually, her story would be told in two operas: a stage play (in German), a musical, a screenplay, a one-woman show, and countless other books and articles.

The last man to enter the mine, in 1938, reported that there was still abundant silver but not enough to justify the expense of removing it.

The Matchless Mine and Baby Doe’s one-room cabin, with its plank floor and small pot-belly stove, has been restored as accurately as possible. Like those she used for insulation, old newspapers cover the walls, providing an atmospheric backdrop for historic photographs of the Tabors and other memorabilia, contrasting Baby Doe’s two very different lives. Most of the period furnishings were added later. Still, a few authentic items remain, such as a delicate white silk scarf from the good years and the magazines, which show a pretty woman with a rosebud mouth and a fuss of curls, her looks enhanced by expensive jewelry.

Baby Doe’s later life is represented by a worn leather satchel in the corner of the room and appears in a photo taken only a few years before she died. Her most prized possession was a framed statue of the Virgin Mary, which hangs on the wall above a narrow, quilt-covered bed. Baby Doe, who turned to religion and a sort of mysticism as time went by and her isolation grew, also used a calendar on display to keep track of the dates on which she said she communed with spirit voices.

Such objects add a haunting air as you soak up the ambiance of the small cabin, which was formally dedicated as a public historic site in 1953. The surrounding images add to the effect as knowledgeable guides spin a true story that helps bring the era and the cabin’s former occupant to life.

The 365-foot Matchless in Fryer Hill was permanently covered when the cabin was opened to the public. But you can peer down into the mine’s grim, shadowed belly or look up at the wooden head frame to contemplate a rusting iron bucket used to lower miners starting a grueling 12-hour shift, for which they were paid $3 a day.

The cable and pulley system controlling the bucket was located in the nearby hoist house, which also holds a blacksmith shop with the mine’s giant, original bellows. The hoist house also displays an intricately detailed scale model of the Matchless, which had seven levels, or shafts, to bring in the fresh air.

Headframe at the Matchless Mine, by Kathy Alexander.

Outside the small cluster of buildings, the sun brightens a deceptively mild-looking landscape, where winter temperatures have been known to drop to 50 degrees below zero.

The Matchless Mine and Baby Doe’s cabin, located 1.2 miles east of Leadville on East 7th Street, is open from 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. daily from Memorial Day through Labor Day and by appointment the rest of the year. For more information, call 800-933-3901. The Leadville area Chamber of Commerce maintains a website at www.leadvilleusa.com.

Leadville today still holds many memories of its glorious past and the impact the Tabors had on this colorful community.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of Colorado

Sources:

Baby Doe Tabor

Bancroft, Caroline; Silver Queen: The Fabulous Story of Baby Doe Tabor, Johnson Publishing Company, 1959

Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame

Karsner, David; Silver Dollar: The Story of the Tabors. New York: Crown Publishers, 1949

Matchless Mine

Wikipedia