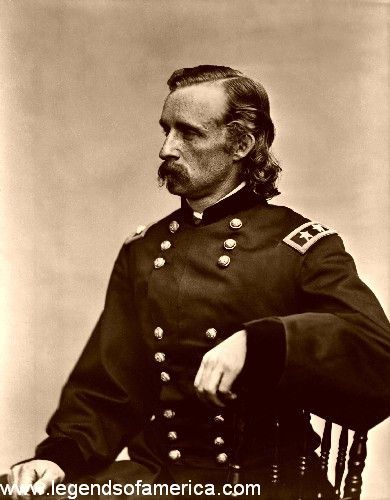

George Armstrong Custer was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the Civil War, he developed a strong reputation, and after it was over, he was dispatched to the West to fight in the Indian Wars.

His disastrous final battle overshadowed his prior achievements. Custer and all the men with him were killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, fighting against a coalition of Native American tribes in a battle that has come to be popularly known in American history as “Custer’s Last Stand.”

George Armstrong Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, on December 5, 1839. His loved ones would call him “Autie” for his entire life, a nickname stemming from his middle name being mispronounced. As a boy, he was constantly distracted by other pursuits and rarely, if ever, established himself from the rest of the children as a student.

In 1855, he attended a Normal School and had his teaching certificate to instruct grammar school by the following year. Not long after, he grew tired of this profession and soon applied to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Custer entered the academy in the fall of 1857 and graduated last in a class of 34 in June 1861. As the Civil War broke out, Custer chose the Cavalry as the branch he wished to serve in and was first assigned staff duty with the Army of the Potomac. He soon distinguished himself as quick to volunteer and easily relied upon.

In November 1862, Custer was introduced to a sought-after young woman, the daughter of Judge Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon. Initially, Libbie fended off the confident young officer’s advances, but soon, the two became sweethearts. Libbie’s father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of his daughter courting someone of a lower social station. Nevertheless, they did, writing letters to one another frequently.

In the first two years of the Civil War, Custer was promoted several times to the rank of Brigadier General of Volunteers, commanding the Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Now, a General, Libbie’s father, began to cool his objections to the young couple. In February 1864, the two were married in Monroe. After the honeymoon, Custer returned to his duties as an officer, but the two continued to correspond incessantly and spent time together whenever the opportunity arose.

He steadily advanced in responsibility and rank through the rest of the war. By the war’s end, in 1865, Custer commanded an entire Cavalry Division holding the rank of Major General. In many cases, Generals led their troops on the battlefield by commanding movements from the rear. Custer, however, distinguished himself as a leader who commanded his troops from the front. Often in charge, he was the very first soldier to engage the enemy. In one instance, he extended so far ahead of his men that the enemy cut him off from the rest of his command.

Men found in Custer a gallant leader worthy of following into battle. He was victorious in most battles he fought against Confederate forces. He narrowly escaped with his life on many occasions, having 11 horses shot from under him and incurring only one wound from a Confederate artillery shell during the Battle of Culpepper Courthouse. As a result, he became known for his legendary “Custer Luck.” After the Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, the huge Volunteer Army was demobilized, and Custer assumed his regular army rank as Captain.

When the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment was created at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1866, Custer was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. The first Colonel of the 7th was Colonel Andrew Smith (1866-1869), and the second Colonel was Colonel Samuel Sturgis (1869-1886). Colonel Smith and Colonel Sturgis were usually on detached service, which placed Custer in command of the Regiment until his death on June 25, 1876.

In 1867, while serving under Major General Winfield Hancock, Custer saw his first real experience in the West. Ostensibly, the campaign was to negotiate peace with the Southern Cheyenne and Kiowa along the Arkansas River. Hancock’s men and Custer set out “to confer with them to ascertain if they want to fight, in which case Hancock will indulge them.” While he scarcely saw combat during his Kansas/Colorado campaign, Custer began to learn the nuances of Indian fighting.

At the end of the campaign, he was suspended from duty for one year. Custer was court-martialed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for being AWOL after abandoning his post to see his wife. He was also charged with conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline and for ordering deserters shot without trial and refusing them medical attention. The court-martial found him guilty of all charges, and he was sentenced to a one-year suspension from rank without pay. A dishonored Custer was then plagued with a different reputation from the venerable one he enjoyed during the Civil War. At the request of Major General Philip H. Sheridan, who wanted Custer for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne, Custer was allowed to return to duty in 1868 before his term of suspension had expired.

In 1868, a conflict between Cheyenne and homesteaders raged. The U.S. Army dispatched a winter campaign responding to Indian raids along the Arkansas River Valley. Now reinstated, Custer was to command the 7th Cavalry for the campaign, culminating with the Battle of the Washita, Oklahoma, on November 27, 1868. At dawn, Custer’s 7th attacked an unsuspecting village of Southern Cheyenne led by Chief Black Kettle. The Battle of Washita should probably be called a massacre instead, as Custer and his men killed warriors, women, and children. Although some sources/articles indicate troops were told to spare women and children, many were slaughtered, including Chief Black Kettle and his wife.

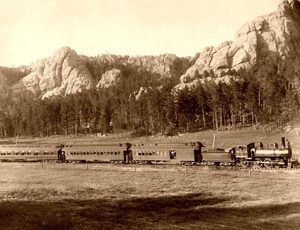

In 1873, the 7th would be called into action again. This time, they were tasked with protecting the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey as it progressed along the Yellowstone River, investigating sites to lay the rail. The Lakota Sioux, among other tribes, had a particular issue with the railroad construction. Soon, the Lakota were attacking survey sites regularly. While neither party realized it at the time, this would be the first contact between Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Chief Gall, and other notable Lakota figures and their famous opponent, George Armstrong Custer.

The following summer, in 1874, Custer led a 1,200-person expedition to the Black Hills of South Dakota, whose possession the United States had guaranteed to the Lakota just six years prior. During an economic depression, rumors began circulating that the Black Hills were rich in gold. Opportunistic men began to enter the area in search of riches. In the meantime, homesteaders had been frequently raided by Lakota war parties.

The army sought to establish a fort in the Black Hills to deter invasions, protect the Lakota land, and provide a site within the Sioux lands to prevent further raiding. The 7th Cavalry was charged with finding a good site for a fort to be built.

At the behest of General Custer, along with the expedition, were two professional miners. During the summer expedition, gold was discovered, and accompanying journalists quickly sent word back east. The rumors of gold in the Black Hills, which had been circulating for over 50 years, had now been confirmed, and a new gold rush was on.

By late 1875, it had become public that high-ranking officials in Washington were involved in a scandal involving the sale of exclusive trading rights at forts and posts along the upper Missouri River region.

The Secretary of War, William Belknap, issued the licenses to trade at military forts. In March and April of 1876, Custer testified before a congressional committee that Secretary Belknap was involved in the graft. In addition, Custer’s testimony attached President Ulysses S. Grant’s brother, Orville, to the corruption. This put Custer in a precarious situation with the Commander-in-Chief overseeing the final planning stages of an offensive on the Lakota and Cheyenne Indians for the upcoming spring.

Custer was eventually allowed to command his 7th Cavalry for the upcoming campaign. In the spring of 1876, the U.S. Army dispatched three massive columns comprising multiple regiments of Cavalry, Infantry, and Artillery. They aimed to clear the area of Lakota and Cheyenne Indians and force them onto the Great Sioux Reservation. Custer’s regiment was part of the most significant column coming from Fort Abraham Lincoln, North Dakota. General Alfred Terry commanded the campaign, and Custer was Terry’s subordinate. On June 22, 1876, under orders from Terry, Custer’s 7th Cavalry was sent ahead of the rest of the column in hopes that they could be the striking force for what was most assuredly a large group of Lakota warriors not far ahead of them.

The original plan for defeating the Lakota called for the three forces under the command of General George Crook, John Gibbon, and Custer to trap the bulk of the Lakota and Cheyenne population between them and deal them a crushing defeat. Custer, however, advanced much more quickly than he had been ordered to do and neared what he thought was a large Indian village on the morning of June 25, 1876. Custer’s rapid advance had put him far ahead of Gibbon’s slower-moving infantry brigades, and unbeknownst to him, General Crook’s forces had been turned back by Crazy Horse and his band at Rosebud Creek.

Based on intelligence suggesting that the Lakota and Cheyenne were about to flee, Custer ordered his 7th Cavalry to attack. By the end of the day, 263 soldiers and approximately 80 Lakota and Cheyenne lay dead. Custer was among them. Less than two weeks later, on July 4, Philadelphia was bursting with pride and nationalism. On the 100th anniversary of the United States, people from all over the world came together to celebrate the theme of “100 Years of Progress.” That day, they would receive word that their famous Civil War hero had been killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory. Americans were confounded in shock and stricken with grief.

Americans were devastated, but none more than the wife of the fallen General, Libbie. She lived on another 57 years after her beloved husband’s death. She tirelessly lobbied public opinion for the rest of her days, portraying her husband as a brave, heroic, and noble figure struck down before his time. Despite his early death, Custer’s name would continue to live in dime novels, art, music, and film. Thanks mainly to Libbie, her husband achieved in death the infamy he sought in life.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2025.

Also See:

Indian War Campaigns and Battles

* Legends of America Reader Steve Busch wrote an article in October of 2012, which we think is also worth sharing. Read about the varying accounts of General Custer’s death, the possible love affair and child with a Cheyenne woman, and more in History Revisited – Digging for the Truth.

Source: National Park Service

There are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.

— George Armstrong Custer