Wagon Mound, New Mexico, a village in Mora County, is located at the foot of a butte called Wagon Mound, an important landmark on the Santa Fe Trail.

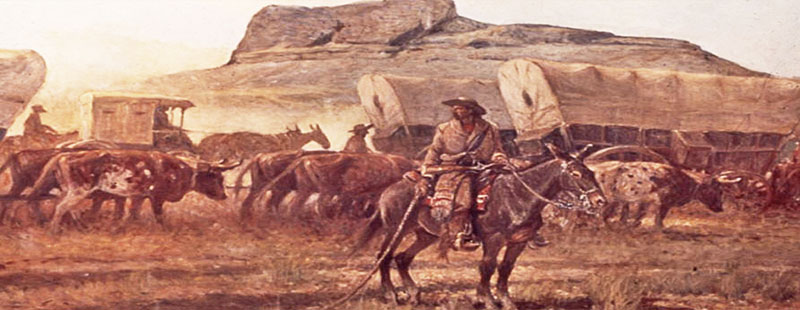

The butte was a navigation point when covered wagon trains and traders traveled along the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail before joining the Mountain Branch near Watrous, about 20 miles further south.

To early travelers, this outcropping of rock resembled a Conestoga wagon drawn by yokes of oxen. It was often touted as “the last great natural landmark on the Santa Fe Trail.” The volcanic outcroppings and lava palisades formed a significant natural landmark. Today, the mound is National Historic Landmark.

In the Santa Clara Canyon, about three miles northwest of the Wagon Mound, were springs known to early Spanish settlers as the Ojo de Santa Clara. The Wagon Mound, visible for 125 miles from the top of the Raton Pass, was a destination for travelers across the arid eastern plains and marked a stopping point and camping site where water could be obtained.

In 1845, Governor Manuel Armijo authorized the last land grant on the northern frontier of the Republic of Mexico to Gervacio Nolan, a naturalized Mexican citizen of French Canadian origin. The Nolan Grant, sometimes called the Santa Clara Grant, was primarily range land and included the site of the future town of Wagon Mound.

When Mexico governed the territory before 1846, there was reputedly a tax collection station near the Wagon Mound, and later there was a stagecoach stop.

In October 1849, Dr. H. White, a popular resident of Santa Fe, was returning with his wife and child from a visit to the East. When they reached a point near Wagon Mound, they were attacked by Indians. White and eleven of his party were murdered and scalped as his wife, child, and nurse were kidnapped. When news of the outrage reached Santa Fe ten days later, Congress appropriated $1,500 for the recovery of the prisoners, and a large body of volunteers joined the regulars and started pursuing the marauders. (See White Massacre)

William Kroenig, in later years a resident of the Mora Valley below Wagon Mound, was at Santa Fe at the time, and he described efforts made by the punitive force:

“The Apache and Ute were very bad. I joined the company at Santa Fe. We went by way of Las Vegas to get the Indians who had killed Dr. White and captured his wife. After a long march toward Taos, we arrived at a place where the Indians had camped the day before. It was about two hours before sunset when we struck the Indians’ trail. Our captain, Jose Maria Valdez, sent me to the major commanding the regulars for two shift horses to locate the camp before night; our request was refused at first, but later, about sunset, he gave us the horses, but it was now too dark, and the Mexicans lost the trail and returned to camp. At daylight, the pursuit was renewed, and after a chase of more than twenty miles, the Indians were overtaken and charged by the regulars. In this charge, the commanding officer was struck in the chest by a stray bullet, but because he had a pair of heavy gauntlets in his blouse, the bullet was deflected. The regulars now dismounted, waiting for the volunteers, the latter securing a position between the Indians and their horses. A skirmish was kept up for some time, the Indians having made the temporary stand to permit the escape, if possible, of their families.

The Indians finally made their escape, and during the pursuit, I saw the body of Mrs. White lying against a willow tree, pierced with arrows. The color, however, had not entirely left her face, showing that she was murdered during the skirmish. Some Indian children were taken as prisoners. The nurse and child of Dr. White were never recovered.”

Another Indian attack occurred on May 19, 1850, near Wagon Mound. The month before, Frank Hendrickson, James Clay, and Thomas E. Branton left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, carrying mail bound for Santa Fe. When they departed, they carried no passengers. About a week into their journey, the three-man party overtook a wagon caravan in central Kansas and was joined by Thomas W. Flournoy and Moses Goldstein. A few days later, they came upon an eastbound ox train. Five members of that group decided they wanted to turn around and go back to Santa Fe. Benjamin Shaw, John Duffy, John Freeman, John Williams, and a German teamster joined the mail express with the others.

By May, the group had made their way to New Mexico, where they were caught in a two-day running battle with a combined force of over 100 Jicarilla Apache and Ute Indians near Wagon Mound. The bodies of all ten men were found near Santa Clara Spring, which is in the canyon northwest of present-day Wagon Mound.

This event, called the Wagon Mound Massacre, coupled with the White Massacre, underscored the need for some military presence. Two years later, in 1851, Fort Union was established. After Fort Union was founded, a road branched off near the Wagon Mound to the fort and connected to the Mountain branch of the Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico.

For more than 60 years, covered wagons passed by Wagon Mound to and from Santa Fe along the western trade route of the 19th century. Trailblazers became fond of the mound, the lush, green meadows, and the abundant water. Aboard the covered wagon caravans were the future ranchers and businessmen that make their homes in the area.

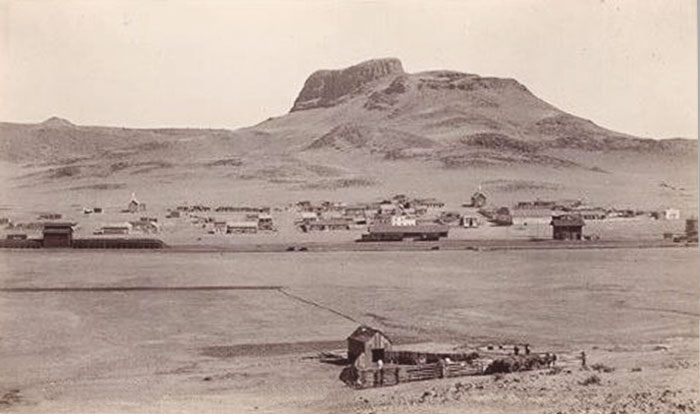

Despite the Indian attacks, a community was founded in 1850 by stockmen attracted by pasturage possibilities. Initially, it was an isolated ranch that housed four families and was called Santa Clara for their patron saint. By 1870, Santa Clara was home to 89 households.

In 1875 William Pinkerton bought the west half of the Nolan Grant, including the site of Wagon Mound, for $40,000. A native of Scotland, Pinkerton had brought improved breeds of sheep to California from Australia and New Zealand after 1848. In New Mexico, he raised sheep near the Wagon Mound and, by 1881, was said to have about 10,000 sheep.

A Santa Clara post office was established on December 8, 1876, but was discontinued just months later, on July 6, 1877.

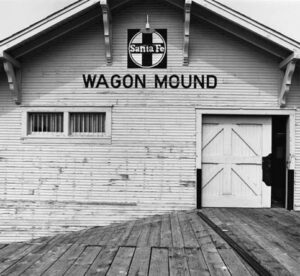

When the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad arrived in 1879, the valley was no longer isolated and more people settled. Soon, it began to flourish and became an important frontier town. In 1881 a post office was established that was called Pinkerton because the name Santa Clara was already in use. However, the name was changed the following year to Wagon Mound.

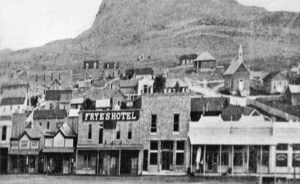

Before long new businesses opened along Wagon Mound’s main street, Railroad Avenue, which faced the tracks and the depot. These businesses were located near the railway station, just a short walk from the center of town. Wagon Mound was often a stopping point and rest stop for travelers making their way to the larger city of Las Vegas, New Mexico. The first recorded hotel in Wagon Mound was run by “Mom and Pop Spears” in 1884.

With the development of ranching and agriculture in Mora County, Wagon Mound became a commercial and social center of the region. Initially, cattle were brought in as part of the cattle boom of the early 1880s. Later sheep predominated, and the railroad built a large sheep dipping plant and an extensive stockyard. Dry farming, especially pinto beans, also became a primary local industry.

In 1900, Wagon Mound had a modern four-room school with 250 students, as well as two churches. It also boasted two mercantile houses, two grocery stores, a bookstore, three bakeries, a butcher shop, two blacksmith shops, two hotels, two restaurants, a livery barn, four saloons, and two dairies. There was also a weekly newspaper called the El Combate printed in Spanish and English. A stagecoach line operated between Wagon Mound and surrounding settlements.

The Santa Clara Hotel and restaurant was erected by Epimenio Martinez, one of Wagon Mound’s leading citizens, in the early 1900s. Martinez had successively engaged in farming and stock raising in Taos, Union, and Colfax Counties before settling in Wagon Mound, where he became one of the most prominent and influential men of the locality. He was also known as the wealthiest man in town. Located on Railroad Avenue just a block from the depot, it was an immediate success. A short walk from the depot., the hotel lodged salesmen and others visiting Wagon Mound.

The Santa Clara Hotel and Restaurant consists of two adjacent, two-story, flat-roofed commercial buildings of unequal height and breadth. At one point, the commercial space included the post office. Today, the Santa Clara Hotel is one of only a few buildings from the railroad era that remain on Railroad Avenue and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

By 1902 Wagon Mound was the largest town in the sparsely populated county and a principal shipping point for cattle, sheep, wool, and agricultural products. It was claimed that as many as two million pounds of wool were shipped annually from Wagon Mound.

In 1906, in partnership with Juan R. Aguilar, Epimenio Martinez established the Wagon Mound Mercantile Company, of which he served as president for 14 years. He was also the organizer of the Bank of Wagon Mound and served as its president. He erected the Wagon Mound Opera House and was one of the leaders in building the Wagon Mound schoolhouse.

In 1909 farmers and ranchers established a Labor Day festival called the Mora County Farmers Harvest Jubilee, an annual celebration that continues today as Bean Day.

By 1913, according to the business directory and a postcard, the hotel’s name was changed briefly to “Frye’s Hotel” after the current manager. The Frye name was soon given to another hotel, a long-running establishment off the main street. Within two years, the name was changed back to Santa Clara, and so remained when Martinez sold a part of the property in 1920 to B.C. Chamblis and his wife.

The village was incorporated in 1918.

By 1921 Santa Clara had become The “Chamblis Hotel and Cafe” and included a wholesale and retail bakery. Chamblis was still the proprietor in 1930 when the name was changed to the “City Hotel and Cafe.” While Chamblis was proprietor, his family occupied living quarters in the hotel behind the office.

Unfortunately, much of historic Railroad Avenue was lost to a devastating tornado on May 31, 1930. However, the Santa Clara Hotel was unscathed.

In the 1930s, Wagon Mound was the chief distributing point for stockmen in the district and the second largest shipping point for livestock in New Mexico. A decline in the significance of local agriculture led to a corresponding decline in the town of Wagon Mound’s importance as a shipping point.

Further, with the automobile’s dominance, Wagon Mound lost its position on the main route for travelers. Passenger service on the railroad was discontinued, and a new highway bypassed the village replacing the route which had passed through town on Railroad Avenue.

The population has declined from a high of about 1,100 in 1950 to about 300 today.

When David Boyd took over the proprietorship of the historic hotel in about 1936, it continued to be called the City Hotel and Cafe. At that time, the hotel had no running water, and rooms were rented for $1.00 and up. Boyd continued to own the hotel into the early 1940s.

Wagon Mound’s population peaked in 1950 at 1,120.

In the following years, the old hotel passed through several owners and ceased to be a hotel in the early 1960s when the owners, Felipe and Helen Lopez, sold the buildings and the hotel furniture separately. Since then, many owners have attempted to restore the buildings and revive the hotel. In the early 1980s, it was called the Conestoga Inn. In the mid-1980s, William Arnold returned to his native Wagon Mound from Colorado, where he had lived for many years. With his wife, Rusty, he bought the Santa Clara Hotel and several other properties. Today, the buildings are vacant. Several other interesting buildings line both sides of Railroad Avenue.

As of the 2020 census, the village population was 266. It still has a public school for children k-12 and an active Catholic Church. The area continues to be a flourishing trading center and a wool and stock-shipping point for Ocate and Mora Valleys.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, September 2022.

Also See:

Indian Terrors on the Santa Fe Trail

Sources:

Federal Writers Project; New Mexico, a Guide to the Colorful State, 1940.

National Register of Historic Places – Santa Clara Hotel

National Register of Historic Places – Wagon Mound Formation

Sangres.com

Village of Wagon Mound

Wikipedia