Located 26 miles southwest of Las Vegas, New Mexico, is the tiny village of San Miguel del Vado (San Michael of the Ford), which started on a Spanish land grant of the same name in 1794. Spanish Governor Fernando Chacon granted 315,000 acres along the upper Pecos River Valley to Lorenzo Marquez and 51 settlers to establish a buffer frontier outpost against raiding Kiowa and Comanche Indians. It was the first village to be founded in the area.

The settlement was concentrated around a defensive rectangular plaza enclosed by contiguous adobe houses. Its early population included Genizaros (Native American slaves or their descendants,) Plains Indians, converted Comanche, and a few Spanish military men. Stock raising and farming, with the help of irrigation from the waters of the Pecos River, was the basis of the settlement’s early livelihood.

Though the early residents feared attacks from the Comanche and Kiowa Indians from the plains, they also welcomed their trading parties. During this time, the village also served as a common starting point for parties of New Mexican Comancheros and ciboleros (buffalo hunters) heading east.

However, San Miguel was also slow in establishing itself as a permanent settlement. It was not until 1803 that the petitioners formally received individual allotments, and the rest of the property was held as communal lands. By the next year, however, the village had grown enough to encourage its residents to petition the Bishop of Durango for a church. Their request was granted, and construction of its two-towered church began the following year.

By 1811, San Miguel’s population outnumbered the declining Pecos Pueblo. That same year, the church was completed, and a school was built in the village. The next year, the Pecos Pueblo priest moved to San Miguel, which at that time supported 230 heads of families. As word of the village’s prosperity spread, a number of influential people believed that it would continue to grow in population and importance.

San Miguel had long served useful as a lookout point for suspected French and American intruders. However, with Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, commercial relations with the United States were welcomed. San Miguel changed from a protective barrier to a commercial entry port for eastern visitors. It also served as the administrative headquarters for the northeastern plains region of New Mexico.

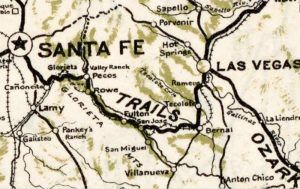

Trader William Becknell, on his first trip along the Santa Fe Trail, found a friendly reception at “the village of St. Michael” after fording the Pecos River on his first trip in 1821. Soon, the village was designated as the port of entry where the Missouri merchants paid their first customs duties to Mexican officials.

In 1824, Meredith Marmaduke, a Santa Fe trader and later Governor of Missouri, said of the village:

“Considerable rejoicing appeared among the natives on our arrival, and they welcomed us with the best music the place afforded. A description can best be given by comparing it to a large brickyard, where there are a number of kilns put up and not burnt, as all the houses are made of bricks dried in the sun, and none of them burnt; all of the roofs are entirely flat; the inhabitants appear to me to be a miserably poor people, but perfectly happy and contented, and appeared very desirous to make our situation as agreeable as possible.”

Mexican Soldier

In 1827, a detachment of Santa Fe Presidio soldiers was stationed at San Miguel for protection against Indians and to reduce Santa Fe Trail smuggling and import tax evasion. By that time, records show that San Miguel’s population was 2,893 people. San Miguel was becoming overcrowded, so much so that Father José Francisco Leyba, the parish priest, suggested that the Mexican government provide oxen and tools to settlers willing to move to the area of present-day Las Vegas. He believed that increased settlement in the northeast would not only alleviate population problems in San Miguel but also protect interior settlements from Indian raids. In addition, many vagrants had taken up residence in San Miguel, and a vagrant law was enacted in 1828, which offered vagrants three lifestyle alternatives: enlistment in the military to help retaliate against hostile Indians, imprisonment, or settlement of land on the frontier. In addition to his many other duties, Father Leyba conducted a priest’s seminary school on the extreme west side of town in the 1930s.

In 1830, a complete customs station manned by Mexican soldiers was established in San Miguel. By this time, the village had become prosperous with the rise and growth of commerce along the Santa Fe Trail. Later, in a journal written by Santa Fe Trail trader James J. Webb in 1844, he described the customs house at San Miguel:

“When we learned the train (caravan) was past Las Vegas, Colburn and I left one afternoon intending to meet it at San Miguel sometime the next day…Messrs. Colburn and Smith took possession of the goods and wagons at San Miguel and entered them and passed through the customs house without any trouble beyond the usual small annoyances from the customs house officers, which were usually satisfied by small loans of money which were never paid or expected to be, and small presents of some kind to which they would take a fancy, generally amounting to twenty-five to one-hundred dollars according to circumstances and number of wagons entered.”

Finally, in 1835, a group of 29 colonists petitioned for a land grant to the northeast of San Miguel. The Las Vegas Land Grant was issued the same year, and people began to move. Between 1835 and 1843, the value of goods traded on the Santa Fe Trail increased from $140,000 to $250,000, and the Las Vegas/San Miguel area became the northeastern trade center and the gateway to New Mexico.

In 1841, the Republic of Texas mounted a commercial and military expedition into New Mexico in an attempt to secure their claims to parts of Northern New Mexico for Texas. They hoped to gain control over the lucrative Santa Fe Trail and further develop the trade links between Texas and New Mexico. However, 300 Texans were captured at La Cuesta (Villanueva) by the forces of Governor Manuel Armijo of the Republic of Mexico and held prisoners at San Miguel for a short time. Two of the Texans were executed in the San Miguel Plaza. The Texans were then forced to march some 2,000 miles to Mexico City and held over the winter of 1841-42 until United States diplomatic efforts secured their release.

In 1846, during the Mexican-American War, General Stephen Kearney arrived at San Miguel, where he gathered the residents in the plaza and gave a rooftop speech proclaiming U.S. annexation. The village then became the seat of San Miguel County and grew to 1,000 inhabitants in 1850.

San Miguel del Vado remained an important stop throughout the days of the Santa Fe Trail, but the growing town of Las Vegas gradually assumed greater importance. Ironically, though the residents of San Miguel had promoted and encouraged the settling of Las Vegas, it would hurt them in the end, as Santa Fe travelers began to bypass the town, making their way on a shorter route directly to San Jose. The county seat was transferred to Las Vegas in 1864.

The 1880 construction of the railroad about one mile north of San Miguel signaled the final decline of the town. Further, major roads through the Pecos River Valley bypassed the town, including Route 66 in 1926 and, later, U.S. Highway 85 and Interstate 25.

Making matters worse, at about the same time, much of the population moved to nearby Ribera because of a smallpox epidemic; others were drawn out of the village to work for the railroad and various mining companies, and their once-thriving sheepherding economy began to suffer due to competition of cattlemen and settlers over ownership and control of the grant’s common lands.

In 1884, the Sisters of Charity opened a school in San Miguel, which operated until 1904. Afterward, it served as a public school for a time.

In 1897, a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court claimed that the San Miguel del Vado Land Grant was held in trust by the Spanish and, later, Mexican governments and claimed the communal lands of the grant as federal property. This ruling reduced the grant’s landholdings from over 300,000 acres to just over 5,000 acres of residential and farming land, stripping the village of the pasture, timber, and other resources provided by the grant, once again contributing to the village’s gradual decline.

By 1900, the population of San Miguel had declined to 450, and by 1930, there were only 217 people in the community.

Today, the old town of San Miguel Del Vado is a National Historic District, officially a part of Ribera, New Mexico.

It is hard to believe that this tiny community with a smattering of homes and adobe ruins once supported nearly 3,000 people.

Today, San Miguel’s old plaza is bisected by New Mexico Highway 3. The county courthouse and jail once stood directly behind the church. Further to the west once stood an old inn. The convent burned down in the 1950s

However, the Pecos River Ford (or Vado) that gave the site its name remains clearly visible in the settlement’s southeast corner. On the northeast side of what was once the plaza is the old territorial house, which later served as a dancehall and a saloon, standing in ruins. Behind here are two adobe structures that appear to be in good condition. Across the street is the fortress-like San Miguel del Vado Church, which still holds regular services. The original 1821 bell still resides in the left tower. An old cemetery associated with the church is about 1,000 feet to the Northwest.

Territorial House, San Miguel, courtesy of New Mexico State University

Though San Miguel remains a valuable part of New Mexico’s past today, its heydays are long past.

The village of San Miguel is located on New Mexico Highway 3, about two miles south of I-25 at exit 323.

To continue on Route 66 and the Santa Fe Trail, return to I-25, travel under the interstate to the north frontage road, travel west about two miles to Road B41D, turn south, and travel about half a mile to San Jose.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Pecos River Valley, New Mexico

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

Sources:

Library of Congress

New Mexico Archaeology

New Mexico State University

National Register of Historic Places Nomination