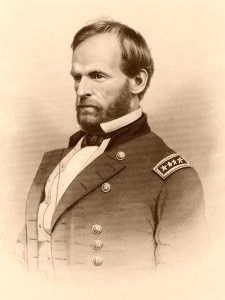

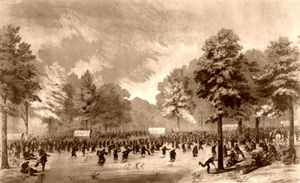

General William T. Sherman’s famous March to the Sea through Georgia in the Civil War, by Felix Darley

by Jacob Dolson Cox, 1910

At Rome, Georgia, when parting with one of the officers he was sending back to Tennessee, Union General William T. Sherman said, “If there’s to be any hard fighting, you will have it to do.” He perfectly understood that Georgia had an insufficient force to thwart his plan or even delay his march. Before leaving Atlanta, he pointed out to one of his principal subordinates that a National army at Columbia, South Carolina, would end the war unless it should be routed and destroyed. Deprived of all the States’ material support but North Carolina, it would be impossible for the Confederate Government to feed its army at Richmond, Virginia, or fill its treasury. The experience it had with the country west of the Mississippi River proved that a region isolated from the rest of the Confederacy would not furnish men or money and could not furnish supplies; while anxiety for their families, who were within the National lines, tempted the soldiers from those States to desert, and weakened the confidence of the whole army.

In such a situation, credit would be destroyed, the Confederate paper money would become worthless, its foreign assistance would be cut off, and the rebellion must end. The one chance left would be for Confederate General Robert E. Lee to break away from Union General Ulysses S. Grant, overwhelm Sherman, and re-establish the Confederate power in a central position by abandoning Virginia. But, this implied that Lee could break away from Grant, who, on the south side of Petersburg, was as near Columbia as his opponent and would be close upon his heels from the moment the lines about Richmond, Virginia were abandoned.

If Sherman, therefore, should reach Columbia with an army that could resist the first onslaught of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the Confederacy’s last hope would be crushed between the national forces meeting from the east and west. Of course, this implied that Union Major General George H. Thomas should, at least, be able to resist Confederate General John Bell Hood until the Eastern campaign should be ended, when, in the general collapse of the Richmond Government, Hood must abandon the hopeless cause, as Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston was forced to do after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender in the following spring.

Establishing a new base upon the sea was a necessary part of such a plan so that the practical separation of the Carolinas from the Gulf States could only be accomplished. This would require the thorough destruction of railway lines in Georgia. The army could live upon the country while marching, but it must have the ordinary means of supply within a very few days from the time of halting, or it would starve. The country through which it moved was hostile. No local government could be made to respond to formal requisitions for subsistence. The wasteful method of foraging made it necessary to move on into new fields. A rapid march to the sea, the occupation of some harbor capable of becoming a fortified base, and the opening of ocean communication lines with the great depots of the North must, therefore, constitute the first part of the vast project. Beyond this, Sherman did not venture to plan in detail and recognizing the possibility that unlooked-for opposition might force a modification, he kept in mind the alternative that he might have to go west rather than east of Macon. He requested that the fleets on the coast watch for his appearance at Morris Island near Charleston, South Carolina; at Ossabaw Sound just south of Savannah, Georgia; and at Pensacola, Florida and Mobile, Alabama. If he should reach Morris Island, it would naturally be by way of Augusta, Georgia, and the left bank of the Savannah River. Ossabaw Sound would, in like manner, indicate the route by way of Milledgeville, Millen, and the valley of the Ogeechee. The Gulf ports would only be chosen if his course to the east should be made impracticable.

On November 12, 1864, communication with the rear was broken. The railway bridge at Allatoona, Georgia, was taken to pieces and carried to the rear to be stored. From the crossing of the Etowah River southward to Atlanta, the road’s whole line was thoroughly destroyed. The foundries, machine shops, and factories at Rome were burned lest they should be again be used by the enemy, and on the 14th, the army was concentrated at Atlanta. The troops from numerous corps and divisions, under various commanders, were estimated to be more than 59,000 men. Furloughed men and recruits hurried so fast to the front in those last days that the muster at Atlanta showed a total of over 62,000.

No pains had been spared to make this a thoroughly efficient force, for an army in an enemy’s country without a base cannot afford to be encumbered with sick or have its trains or its artillery delayed by weak or insufficient teams. The artillery was reduced to about one gun to a thousand men, and the batteries usually to four guns, each with eight good horses to each gun or caisson. Twenty days’ rations were in hand, and 200 rounds of ammunition of all kinds were in the wagons. Droves of beef cattle to furnish the meat ration was ready to accompany the march, and these grew larger rather than smaller as the army moved through the country.

The determination to abandon Atlanta also involved the undoing of much work that had been done there in the early autumn. As the National forces could not use the town, the defenses must be destroyed, the workshops, mills, and depots ruined and burned. This task had been given to Colonel Poe, Chief Engineer, and was completed when the army was assembled and ready to march southward. On the morning of November 15, the movement began. The two corps of each wing were ordered to march upon separate roads, at first diverging sharply and threatening both Macon and Augusta. Sherman himself accompanied the left wing, which followed the line of railway leading from Atlanta to Augusta; for, by doing so, he could get the earliest and best information of any new efforts the Confederate Government might make for the defense of the Carolinas. In this way, he could best decide upon his columns’ proper direction after reaching the Oconee River.

The general line of Sherman’s march was between the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers. However, he sent his right wing, at first, along the Macon Railroad by more westerly routes, to deceive the enemy and to drive off Confederate General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry and some 3,000 Georgia Militia, under General G. W. Smith, which had been assembled at Lovejoy’s Station for some days. General Oliver O. Howard’s right (Fifteenth Corps) marched by way of Jonesborough, McDonough, and Indian Spring to the crossing of the Ocmulgee River at Planters’ Factory, the Seventeenth Corps keeping a little farther east, but reaching the river at the same place. With most of the cavalry, Union General Judson Kilpatrick was upon this flank and drove the enemy’s skirmishers before him to Lovejoy’s Station. Smith had retired rapidly upon Macon with his infantry, but the old lines at Lovejoy’s Station were held by two cavalry brigades with two artillery pieces. Kilpatrick dismounted his men and charged the works on foot, carrying them handsomely. He followed his success with a rapid attack by another column, which captured the guns and followed the retreating enemy some miles toward Macon. The cavalry continued its demonstrations nearly to Forsyth, creating the impression of an advance in force in that direction; then, it turned eastward and crossed the Ocmulgee River with the infantry.

A section of pontoon train was with each corps, and Howard put down two bridges; but, though his head of the column reached Planters’ Factory on the 18th, and the bridges were kept full day and night, it was not till the morning of the 20th that the rear guard was able to cross. The bank on the eastern side of the river was steep and slippery from rain, making it tedious work getting the trains up the hill. His heads of columns were pushing forward in the meantime and reached Clinton, a few miles north of Macon, by the time the rear was over the river. Kilpatrick now made a feint upon Macon, striking the railway a little east of the town, capturing and destroying a train of cars, and tearing up the track for a mile. Undercover of this demonstration and while the cavalry was holding all roads north and east of Macon, Howard’s infantry, on November 22, closed up toward Gordon, a station on the Savannah railroad, 20 miles eastward.

Union General Charles R. Woods’s division of the Fifteenth Corps brought up the rear and approached Griswoldville. The left wing, which Sherman accompanied, applied itself in earnest to the destruction of the railway from Atlanta to Augusta, making thorough work of it to Madison, 70 miles from Atlanta, and destroying the Oconee River bridge, 10-12 miles further on. Here, the divergence between the wings was greatest, the distance from General Henry Slocum’s left to Kilpatrick, on the right, being 50 miles in a direct line.

Sherman’s advance from Atlanta drew from Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, a rattling volley of telegraphic dispatches to all Confederate civil and military officials. In these, he made much of the fact that he had ordered General Richard Taylor in Alabama to move with his available forces into Georgia; but, Taylor had no available forces and could only go in person to Macon, where he arrived on November 22, just in time to meet Governor Joseph E. Brown with his Adjutant, Robert Toombs, escaping from the State Capitol on the approach of General Slocum’s columns. The only organized troops were Wheeler’s cavalry, Smith’s division of Georgia Militia, and a couple of local volunteer battalions. General Howell Cobb was nominally Confederate commander of “reserves,” but there seems to have been no reserves to command.

Beauregard issued from Corinth, Mississippi, a proclamation to the people of Georgia, calling upon them to arise for the defense of the State and to “obstruct and destroy all roads in Sherman’s front, flank, and rear,” assuring them that the enemy would then starve in their midst. He also strove to raise vague hopes by announcing that he was hastening to join them in defense of their homes and firesides. A more practical step was his order to General Hood to begin the Tennessee campaign, the only counter-stroke in his power. At Milledgeville, Georgia, the approach of Sherman was met by an Act of the Legislature to levy en masse the population, with a hysterical preamble, picturing the National general as an ogre, and urging the people “to die freemen rather than live slaves.” To have been of any use, the act should have been passed a month before, when Hood was starting west from Gadsden. It was now only a confession of terror, for there was no time to organize. Any disposition of the inhabitants along his route to destroy roads was effectually checked by Sherman’s, making it known that the houses and property of those who did so would be destroyed. Such opposition to a large army can never be of real use; its common effect is only to increase by retaliation the miseries of the unfortunate people along the line of march, and in this case, there was, besides, no lack of evidence that most of them were heartily tired of the war, and had lost all the enthusiasm which leads to self-sacrifice.

However, as the troops continued to move forward, they would encounter resistance and participate in numerous skirmishes, including the Battle of Griswoldville on November 22 when Union Brigadier General Charles Walcutt’s six infantry regiments ran into the Georgia Militia. The Union force withstood three determined charges before receiving reinforcements of one infantry regiment and two cavalry regiments. The Rebels did not attack again and soon retired. The Union victory resulted in estimated casualties of 62 Union and 650 Confederate.

The right wing began destroying the railway at Griswoldville, and of the 100 miles between that station and Millen, Georgia, very little of the road was left. General Oliver O. Howard found crossing the Oconee near Ball’s Ferry a difficult operation, for the river was up and the current so swift that the ferry could not be used. Confederate General Wheeler’s cavalry made some resistance from the other side. A detachment of corps, directed by the engineers, succeeded in constructing a flying bridge some two miles above the ferry. Getting over to the left bank, moved down to the principal road, which had been cleared of the enemy by the artillery on the other side. The pontoons were then laid, and the march resumed.

Sherman ordered Kilpatrick to make a considerable detour to the north, feinting strongly on Augusta but, trying hard to reach and destroy the critical railway bridge and trestles at Briar Creek, near Waynesboro, halfway between Augusta and Millen. He was then to hurry on Millen in the hope of releasing the National prisoners of war who were in a prison camp near that place. Kilpatrick moved by one of the principal roads to Augusta, giving out that he was marching on that city. After he had passed the Ogeechee Shoals, Wheeler heard of his movement and rapidly concentrated his force on the Augusta road, where it debouches from the swamps of Briar Creek. In obedience to his orders, Kilpatrick turned the head of his columns to the right, upon the road running from Warrenton to Waynesborough, and they were well on their way to the latter place before Wheeler was aware of it.

Murray’s brigade was in the rear, and two of his regiments, the Eighth Indiana and Second Kentucky, constituted the rear guard. These became too far separated from the column when they camped near Sylvan Grove. Wheeler heard of their whereabouts and attacked them in the middle of the night. Though surprised and driven from their camps, the regiments stoutly fought their way back.

Confederate General Wheeler followed up persistently with his superior forces, harassing the rear and flank of the column and causing some confusion, but gaining no significant advantage, except that Kilpatrick was obliged to abandon the effort to burn the Briar Creek bridge and trestles and to turn his line of march southwesterly from Waynesborough, after destroying a mile or two of the railroad. He reported that he learned that the Millen prisoners had been removed and determined to rejoin the Louisville army. Early in the morning of the 28th, Kilpatrick himself narrowly escaped capture, having improperly made his quarters for the night at some distance from the body of his command, the Ninth Michigan being with him as a guard. The enemy got between him and the column, and it was with no little difficulty he succeeded in cutting his way out and saving himself from the consequences of his own folly.

The long causeway and bridge at Buck Head Creek were held while the division passed, by Colonel Heath and the Fifth Ohio, with two howitzers, and Wheeler received a severe check. The bridge was destroyed, and Kilpatrick took a strong position at Reynolds’s plantation. Wheeler then attacked in force but was decisively repulsed, and Kilpatrick effected his junction with the infantry without further molestation. Wheeler’s whole corps was engaged in this series of sharp skirmishes, and he boasted loudly that he had routed Kilpatrick, causing him to fly in confusion with a loss of nearly 200 in killed, wounded, and captured. Chafing at this rebuff, Kilpatrick obtained permission to deliver a return blow, and after resting his horses a day or two, marched from Louisville on Waynesborough. He attacked Wheeler near the town and drove him by spirited charges from three successive barricades, chasing him through Waynesboro and over Briar Creek. Wheeler admitted that it was with difficulty. He “succeeded in withdrawing” from his position at the town but sought to take off the edge of his chagrin by reporting that the Fourteenth Corps attacked him as by Kilpatrick’s cavalry.

Millen was reached on December 3, and the direct railway communication between Savannah and Augusta was cut. Three corps now moved down the narrowing space between the Savannah and Ogeechee Rivers. From Millen onward, the march of the whole army was methodic progress with no noticeable opposition. Even Wheeler’s horsemen generally kept a respectful distance and soon crossed to the Savannah River’s left bank. The country became more sandy, corn and grain grew scarcer, and all began to realize that they were approaching the low country bordering the sea, where but little breadstuffs or forage would be found. On December 9th and 10th, the columns closed in upon the defenses of Savannah.

Skillful infantry scouts were sent out to open communication with the fleet and cut the Gulf Railway, thus severing the city’s last connection with the south.

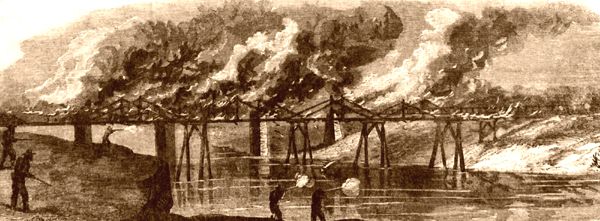

Sherman’s troops burned bridges.

During Sherman’s triumphant march, the destruction of railway communication between the Confederate Army at Richmond, Virginia, and the Gulf States had been essential for Sherman’s purpose. He spared no pains to do this thoroughly. A battalion of mechanics was selected and furnished with tools for ripping the rails from the cross-ties and twisting them when heated, and kept these constantly at work; but, the infantry on the march became expert in methods of their own, and the cavalry also joined in the work, though the almost constant skirmishing on the flanks and rear of the army usually kept the mounted troops otherwise employed. A division of infantry would be extended along the railway line about the length of its proper front. The men, stacking arms, would cluster along one side of the track, and at the word of command, lifting together, would raise the line of rail with the ties as high as their shoulders; then at another command, they would let the whole drop, stepping back out of the way as it fell.

The heavy fall would shake loose many of the spikes and chairs, and seizing the loosened rails, the men, using them as levers, would quickly pry off the rest. The cross-ties would now be piled up like cob-houses, and with these and other fuel, a brisk fire would be made; the rails were piled upon the fire, and in half an hour would be red hot in the middle. Seizing the rail now by the two ends, the soldiers would twist it about a tree or interlace and twine the whole pile together in great iron knots, making them useless for anything but old iron and most unmanageable and troublesome, even to convey away to a mill. In this way, it was not difficult for a corps marching along the railway to destroy, in a day, ten or 15 miles of the track most completely; and General William T. Sherman himself gave a close watch to the work to see that it was not slighted. All machine shops, stations, bridges, and culverts were destroyed, and the masonry was blown up.

The extent of the line destroyed was enormous. From the Etowah River through Atlanta southward to Lovejoy’s Station, nothing was left of the road for a hundred miles. From Fairburn through Atlanta eastward to Madison and the Oconee River, another hundred miles, the destruction was equally complete. From Gordon southeastwardly, the Central road’s ruin was continued to the very suburbs of Savannah, 160 miles. Then there were serious breaks in the branch road from Gordon northward through Milledgeville and connected Augusta and Millen. So great a destruction would have been a prolonged and severe interruption even at the North. Still, the blockade of Southern ports and the small manufacturing facilities in the Confederate States made the damage practically irreparable. The lines that were wrecked were the only ones that then connected the Gulf States with the Carolinas. Even if Sherman had not marched northward from Savannah, the Confederacy resources would have been seriously crippled.

The forage of the country was also destroyed throughout a belt 50-60 miles in width. Both armies cooperated in this; the Confederate cavalry burning it so it would not fall into the hands of the National Army. The latter left none that they could not themselves use, so that wagon transportation of military supplies across the belt might be made more difficult.

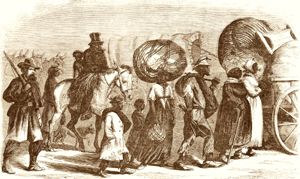

As the campaign progressed, many black men, women, and children attached themselves to the columns and accompanied the march. This was contrary to Sherman’s wishes, who felt the embarrassment of having thousands of mouths added to the number of those who must be fed from the country as he moved. Those who had less responsibility for the campaign did not trouble themselves so much with this consideration. The men in the ranks generally encouraged the slaves to leave the plantations. The former slaves, themselves, found it hard to let slip the present opportunity of getting out of bondage, and their uneducated minds could not estimate the hope of freedom at the close of the war as having much weight against the instant liberty which was to be had by simply tramping away after the blue-coated soldiers.

The natural result was that numberless gypsy camps fringed the regular temporary camps of the troops. The black families, old and young, endured every privation, living upon the soldiers’ charity, helping themselves to what they could glean in the track of the army foragers. On the march, they trudged along, making no complaint, full of simple faith that “Lincoln’s men” were leading them to abodes of ease and plenty.

When the lower and less fruitful lands were reached, the embarrassment and military annoyance increased.

Losing patience at the failure of all orders and appeals to these poor people to stay at home, Union General Jefferson C. Davis (commanding the Fourteenth Corps) ordered the pontoon bridge at Ebenezer Creek to be taken up before the refugees who were following had crossed, to leave them on the further bank of the unfordable stream and thus disembarrass the marching troops. It would be unjust to that officer to believe that the order would have been given if the effect had been foreseen. The poor refugees had their hearts so set on liberation. The fear of falling into the hands of the Confederate cavalry was so great that, with wild wailings and cries, the great crowd rushed, like a stampeded drove of cattle, into the water, those who could not swim as well as those who could. Many were drowned despite the earnest efforts of the soldiers to help them. As soon as the character of the unthinking rush and panic was seen, all was done that could be done to save them from the water, but the loss of life was still significant.

When Savannah was reached, many refugees with all the columns were placed on the Sea Islands, under government officers’ care, and added largely to the colonies already established there. Afterward, the Freedmen’s Bureau was the necessary outgrowth of this organization in a great measure.

The subsistence of the army upon the country was a necessary part of Sherman’s plan, and the bizarre character given it by the humor of the soldiers has made it a striking feature of the march. However, it is important to distinguish between what was planned and ordered and what was an accidental growth of the soldier’s disposition to make sport of everything that could be turned to amusement. The orders issued were of a strictly proper military character. The trains’ supplies were to be treated as a reserve to be drawn upon only in case of necessity, and systematic foraging upon the country for daily food was the regular means of getting rations. Each regiment organized a foraging party of about one-twentieth of its numbers under the command of an officer.

Foraging party during the Civil War

These parties set out first of all, in the morning, those of the same brigades and divisions working in concert, keeping near enough together to be mutual support if attacked by the enemy, and aiming to rejoin the column at the halting-place appointed for the end of the day’s march. The foragers became the beau ideal of partisan troops. Their self-confidence and daring increased to a wonderful pitch, and no organized line of skirmishers could so quickly clear the head of the column of the opposing cavalry of the enemy. Nothing short of an entrenched line of battle could stop them, and when they were far scattered on the flank, plying their vocation, if a body of hostile cavalry approached, a singular sight was to be seen. Here and there, from barn, granary and smoke-house, and the kitchen gardens of the plantations, isolated foragers would hasten by converging lines, driving before them the laden mule heaped high with vegetables, smoked bacon, fresh meat, and poultry. As soon as two or three of these met, one would drive the animals, and the others, from fence corners or behind trees, would begin a bold skirmish, their Springfield rifles giving them the advantage in range over the carbines of the horsemen. As they were pressed, they would continue falling back and assembling, the regimental platoons falling in beside each other till their line of fire would become too hot for their opponents, and these would retire reporting that they had driven in the skirmishers upon the main column which was probably miles away. The work of foraging would then be resumed. It was of the rarest possible occurrence that Wheeler’s men broke through these enterprising flankers and approached the line troops. As the columns approached the place designated for their evening camp, they would find this ludicrous but most bountiful supply train waiting for them at every fork of the road, with as much regularity as a railway train running on “schedule time.”

They brought in all animals that could be applied to army use. As the mule teams or artillery horses broke down in pulling through the swamps, which made a wide border for every stream, fresh animals were ready so that on reaching Savannah, the teams were fat and sleek and in far better condition than they had been at Atlanta.

The orders given these parties forbade their entering occupied private houses or meddling with private property of the kinds not included in war supplies and munitions. In the best-disciplined divisions, these orders were enforced. However, discipline in armies is apt to be uneven. Among 60,000 men, there are men enough who are willing to become robbers, and officers enough who are willing to wink at irregularities or to share the loot, to make such a march a terrible scourge to any country.

A bad eminence in this respect was generally accorded to Kilpatrick, whose notorious immoralities and rapacity set so demoralizing an example to his troops that the best disciplinarians among his subordinates could only mitigate its influence. His enterprise and daring had made his two brigades usually hold their own against the dozen which Wheeler commanded, and the value of his services made his commander willing to be ignorant of escapades which he could hardly condone, and which on more than one occasion came near resulting in Kilpatrick’s capture and the rout of his command. But he was quite capable, in a night attack of this kind, of mounting, bare-backed, the first animal, horse or mule, that came to hand, and charging in his shirt at the head of his troopers with a dare-devil recklessness that dismayed his opponents and imparted his daring to his men.

Then, the confirmed and habitual stragglers soon became numerous enough to be a nuisance upon the line of march. Here again, the difference in portions of the army was very marked. In some brigades, every regiment was made to keep its rearguard to prevent straggling. The brigade provost-guard marched in rear of all, arresting any who sought to leave the ranks and reporting the regimental commander who allowed his men to scatter. But little by little, the stragglers became numerous enough to cause serious complaint, and they followed the command without joining it for days together, living on the country and evading the labors of their comrades. It was to these that the name “bummer” was appropriately applied. This class was numerous in the Confederate and the National Army, in proportion to its strength. The Southern people cried out for the most summary execution of military justice against them. Responsible persons addressed specific complaints to the Confederate War Secretary, charging robbery and pillage of the most scandalous kinds against their own troops. Their leading newspapers demanded the cashiering and shooting of colonels and other officers and declared their conduct worse than the enemies. It is perhaps vain to hope that a great war can ever be conducted without abuses of this kind, and we may congratulate ourselves that the wrongs done were almost without exception to property and that murders, rapes, and other heinous personal offenses were nearly unknown.

The great mass of the officers and soldiers of the line worked hard and continuously, day by day, marching in bridging streams, making corduroy roads through the swamps, lifting the wagons, and cannon from mud-holes, and in tearing up the railways. They saw little or nothing of the country’s people and knew comparatively little of the foragers’ work, except to enjoy the fruits of it and the unspeakable ludicrousness of the cavalcade as it came in at night. The foragers turned into beasts of burden, oxen, and cows, as well as the horses and mules. Here would be a silver-mounted family carriage drawn by a jackass and a cow, loaded inside and out with everything the country produced, vegetable and animal, dead and alive. An ox-cart, similarly loaded and drawn by a nondescript tandem team, would be equally unpredictable. Perched upon the top would be a ragged forager, rigged out in a fur hat of a fashion worn by dandies of a century ago, or a dress coat which had done service at stylish balls of a former generation. The jibes and jeers, the fun and the practical jokes ran down the whole line as the procession came in, and no masquerade in carnival could compare with it for original humor and rollicking enjoyment.

The weather had generally been perfect. A flurry of snow and a sharp, cold wind had lasted for a day or two about November 23, but the Indian summer set in after that, and on December 8, the heat was even sultry. The camps in the open pine-woods, the bonfires along the railways, the occasional sham-battles at night, with blazing pine-knots for weapons whirling in the darkness, all combined to leave upon the minds of officers and men the impression of a vast holiday frolic; and in the reunions of the veterans since the war, this campaign has always been a romantic dream more than a reality, and no chorus rings out with so joyous a swell as when they join in the refrain, “As we were marching through Georgia.”

Jacob Dolson Cox, 1910. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2022.

Source: This article was excerpted from Jacob Dolson Cox’s 1910 book, The March to the Sea: Franklin and Nashville, published by C. Scribner, 1910. However, please note the text as it appears here is far from verbatim, as it has been heavily edited, truncated, and updated.

Civil War soldiers moving through the country.

Also See: