By Herbert Eugene Bolton, 1918

By the mid 1500s, Spanish interest in Florida had been aroused by the journey of Cabeza De Vaca, who had explored part of the area in April 1528. Though only four of the 600 men of the expedition survived, their tales of the people and resources aroused the interest of Spanish authorities. This interest was quickened to a lively heat when, late in 1543, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado and the remnants of Hernando De Soto’s band, at last, straggled into Mexico City. It would appear that hardships and failures could not impair a Spaniard’s ability for story-telling, for Moscoso and his tattered comrades were soon spinning for others the golden web of romance in which they had been snared. Glowing pictures they gave of the north country, especially of Coosa (in Alabama), where they had been well fed and where one or two of their number had remained to dally with Creek damsels. The Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, ambitious to extend his power into the Northern Mystery, offered to finance an expedition if Luis de Moscoso Alvarado would undertake it. But, while Moscoso’s zeal for golden Florida might inspire his imagination to dazzling flights of fancy, it was inadequate to stir his feet one step again in that direction. So, Mendoza’s project came to nothing.

It was noticed that the Mexicans valued highly some of the fur apparel brought back by Moscoso’s men. The following year, in 1544, two Spanish gentlemen sought from the King the right to conquer Florida to bring deer skins and furs into Mexico to discover pearls, mines, and whatever other marvels had embroidered Moscoso’s romance. But, the King refused their petition. In his refusal, he was partly influenced by religious and humane motives. Despite the presence of priests and friars, the various expeditions to the north thus far had taken no time from treasure hunting to convert natives or to establish missions. The Church was now considering the question of sending out its own expedition to Florida, unhampered by slave-catching soldiers.

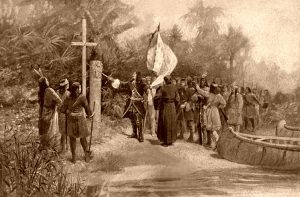

Perhaps this idea of conquest by the Cross, unaided — and unhampered — by the sword, was born in the mind of Fray Luis Cancer, a devout and learned Dominican. Fray Luis was living in the convent of Santo Domingo in Mexico City not long after Cabeza De Vaca and Luis de Moscoso Alvarado arrived with their wonder tales. The account of the hundreds of savages who had followed Vaca from village to village must have moved the good friar’s heart with zeal and pity. And, he can have been no less stirred by the tales told by Moscoso’s men of the gallant butchery their swords had done — of the clanking chains that made music on the day’s march and the sharp whisper in the night of the flint, as it pressed against an iron collar. Fray Luis desired to see all heathen made free in God’s favor. The oppression his countrymen practiced upon the natives filled him with horror. As a missionary, first in Espanola and then in Puerto Rico, he had seen the hopelessness of trying to spread religion in territories that ruthless conquerors were swiftly depopulating. He had, therefore, gone to Guatemala to the monastery of Santiago, whose head was the noble Las Casas. At that time, one province of Guatemala was known as the “Land of War” because of the ferocity of its natives. Las Casas had influenced the Governor to forbid that territory to Spaniards for five years. Then, he sent Fray Luis, who had learned the natives’ language, to the chief to request permission for the monks to come there. With his gentle words, Fray Luis also took little gifts, trinkets, mirrors, and beads of bright colors that would delight the Indians.

He made so good an impression on the chief that the permission he sought was readily given. And, in a few years, the Land of War became the Land of the True Peace — Vera Paz — where no Spaniards dwelt, save a few Dominican friars, and where, in morning and evening, Indian voices chanted the sacred songs to the accompaniment of the Indian flutes and drums which had formerly quickened to frenzy the warriors setting out to slaughter. And, for this spiritual conquest, Fray Luis had received the title of Alferez de la Fe, Standard Bearer of the Faith.

But, Fray Luis was not content to eat the fruit of his labors in Vera Paz. The Standard Bearer would push on to another frontier. He went to Mexico City in 1546 because he would find the latest reports of newly discovered countries. Here, Fray Luis heard the stories that had been told there by Cabeza De Vaca and Luis de Moscoso Alvarado and resolved to bear his standard to Florida.

He found willing comrades in three monks of his order, Gregorio de Beteta, Juan Garcia, and Diego de Tolosa. Fray Gregorio and Fray Juan had already made three or four unsuccessful attempts to reach Florida by land from Mexico, with a total misapprehension regarding distance and direction. His plans were consummated under the orders of Las Casas. Fray Luis went to Spain to urge the great project with the King. His petition was soon granted. When he returned to Mexico in 1548, he had the royal authority to establish a mission at some point in Florida where Spaniards had not yet spilled native blood. In 1549, Fray Luis and his three companions sailed from Vera Cruz in an unarmed vessel. At Havana, he took on board a converted native girl named Magdalena, who was to act as interpreter and guide. Perhaps it was almost impossible for the pilot to distinguish one inlet from another, with certainty, on that much-indented coastline, where the low shore presents no variation to the eye for miles; for, instead of landing at a new point, the monks first touched Florida soil in the vicinity of Tampa Bay. The natives of Tampa Bay were hostile, with memories of Hernando De Soto.

There were empty huts nearby and a background of forest in which it seemed nothing stirred. Fray Diego went ashore and climbed a tree at some distance from the beach. Immediately, a score of Indians emerged from the forest. Despite the pilot’s warnings, Fray Luis and Magdalena, and another monk named Fuentes hurried after Diego through the water to their waists. “Our Lord knows what haste I made lest they should slay the monk before hearing what we were about,” Fray Luis writes. As he climbed the bank, he paused to fall on his knees and pray for grace and divine help.

Then he took out of his sleeves some of the trinkets he had brought because he wrote, “Deeds are love, and gifts shatter rocks.”‘ After these gifts, the natives were willing that the friars and Magdalena should kneel among them, reciting the litanies, and, to Fray Luis’s joy, they also knelt and appeared pleased with the prayers and the rosaries.

They seemed so friendly that Fray Luis permitted Fray Diego, Fuentes, and Magdalena to remain with them and go on a day and a half’s journey by land to a good harbor of which the Indians had told them. He and Fray Gregorio returned to the ship. It took the pilot eight days to find the new harbor and eight more to enter. It was on the feast of Corpus Christi that the ship dropped anchor. Fray Luis and Fray Juan landed and said Mass. To their apprehension, they saw no signs of Fray Diego, Fuentes, or Indians. On the next day, as they searched, an Indian came out of the woods carrying, in token of peace, a rod topped with white palm leaves, and he appeared to assure Fray Luis that Fray Diego and his companions were safe and would be brought to him. The next day, as Fray Luis, with Fray Juan and Fray Gregorio, rowed towards the shore, the natives waded to meet them, bringing fish and skins to trade for trinkets. One Indian would take nothing but a little wooden cross, which he kissed as he had seen the monks do — much to the delight of Fray Luis. If the pious monk’s joy at this incident was dimmed a few moments later, when he waded inshore and discovered Magdalena naked among the tribeswomen, it kindled again at her assurance that Diego and Fuentes were safe in the cacique’s house. Fray Luis learned how little truth was in her words when he returned to the ship. There, he found a Spaniard, once a soldier of De Soto’s army, whom the Indians of this tribe had enslaved. This man informed him that the Indians had already slain Fray Diego and the monk, Fuentes; he had held Diego’s scalp in his hands.

To plead that he forsake his mission and sail away to safer shores, Fray Luis had but one answer. Where his comrades in the faith, acting under his orders, had fallen, there he would remain. Though storms prevented him from landing for two days, he refused to accept the assertions of his shipmates — that God sent the storms to keep him from death among the Indians. And, at last, he came again to shore through the lashing and roaring of sea and wind. Armed natives painted for war could be seen grouped on the bank above the slope to the beach. “For the love of God, wait a little; do not land,” Fray Gregorio entreated. But Fray Luis had already leaped into the water. He turned back once upon reaching the beach, but it was to call Gregorio or Juan to bring him a small cross he had forgotten. When Gregorio cried, “Father, for mercy’s sake, will not your reverence come for it, as there is no one here who will take it to you,” Fray Luis went on towards the hill. He knelt in prayer for a few moments at its foot, then began the ascent. Midway, the Indians closed about him, swinging their clubs. He cried out once, loudly before their blows struck him down. Those in the boat heard his cry and saw the Indians clubbing and slashing at his body as they thrust it down the hill. Then, a shower of arrows falling upon their boat made them pull away in haste to the ship. The next day, the vessel set sail and, three weeks later, anchored off Vera Cruz.

King Philip II had come to the throne, the master of Europe. His father, King Charles V, had been not only sovereign ruler of Spain, the Netherlands, Naples, a part of central Italy, of Navarre, and Emperor of Germany by-election, but he had hoped to become master of England also and to leave in his heir’s hands a world all Spanish and all Catholic. Philip II inherited his father’s power and his father’s dream. His stubbornness and zeal would have been greater if his natural abilities were less. He had seen the march of Spanish power not unattended by affronting incidents. In 1520, a monk named Luther had defied Philip’s father, the Emperor, to his face. The Reformation was spreading. Huguenots were powerful in France’s domestic politics, and France was threatening Spain’s American possessions. Her fishermen had passed yearly in increasing numbers between the Banks of Newfoundland and their home ports. And, a mariner of several cross-sea voyages, Jacques Cartier, had discovered the St. Lawrence River and had set off again in 1540 to people “a country called Canada.”

But, these voyages of discovery were not the worst of France’s insults to Spain. French pirates had formed the habit of darting down on Spanish treasure ships and appropriating their contents. They had also sacked Spanish ports in the islands. Many of these pirates were Huguenots, “Lutheran heretics,” as the Spaniards called them. Another danger also was beginning to appear on the horizon, though it was as yet but a speck. It hailed from England, whose mariners began to fare forth into all seas for trade and plunder. They were trending towards the opinion of King Francis of France that God had not created the gold of the New World only for Castilians. A train of Spanish treasure displayed in London had set more than one stout seaman to head-scratch over this world’s inequalities and how best to readjust the balances. There was reason enough, then, for Philip’s fear that large portions of the New World might readily be snatched from Spain by heretical seamen, and Philip was as fierce in the pursuit of his own power as in his zeal for his religion.

The slow-moving treasure fleets from Mexico and Havana sailed past Florida through the Bahama Channel, which Juan Ponce de Leon had discovered, and on to the Azores and Spain. The channel was not only the favorite hunting place of pirates — so that the Spanish treasure ships no longer dared go singly but, now combined for protection; it was also the home of storms. The fury of its winds had already driven too many vessels laden with gold upon the Florida coast, yet there were no relief ports. Cargoes had thus been wholly lost, and sailors and passengers murdered by the Indians. To these dangers was the fear that the French designed to plant a colony on the Florida coast near the channel so that they might seize Spanish vessels in case of war, for no one could pass without their seeing it.

So, on Philip’s order, Viceroy Velasco bestirred himself to raise a colony for Coosa and some other point in Florida. The other point selected was Santa Elena, now Port Royal, South Carolina. When all was ready, the company comprised no less than 1500 people. Six of the 12 captains in the force had been with De Soto. In the party, there were Coosa women who had followed the Spaniards to Mexico. They were now homeward-bound. At the head of the colony went Tristan de Luna y Arellano, the same Don Tristan who had been Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s second in command in the Cibola enterprise 18 years before. The departure of the expedition was celebrated with great pomp. Velasco himself crossed the mountains to Vera Cruz to see it off.

But, this expedition was to be another record of disaster and failure. Arellano brought his fleet to anchor in Pensacola Bay and then dispatched three vessels for Santa Elena. Before his supplies were unloaded, a tremendous hurricane swept the Bay and destroyed most of his ships, with a great loss of life. So violent was the storm that it tossed one vessel, like a nutshell, upon the green shore. Some of the terror-struck soldiers saw the shrieking demons of Hell striding the low, racing, black clouds. The outguards of the storm attacked the three ships bound for the Carolina coast and drove them south so that they returned to Mexico by way of Cuba.

The survivors at Pensacola Bay were soon in straits for food. So Arellano, leaving a garrison on the coast, sent about 1,000 of his colonists — men, women, and children — to Santa Cruz de Nanipacna, forty leagues inland on a large river, probably in Monroe County, Alabama. But, these colonists in the fruitful land were like the 17-year locusts; they ate everything from the Indians‘ stores of maize and beans to palm shoots, acorns, and grass seeds – but produced nothing. Soon, an exploring band of 300 was sent toward the famed Coosa for more food. They reached it after a hundred days of weary marching over De Soto’s old trail. Though the natives had small reason to love De Soto’s countrymen, they treated the Spaniards well and fed them bountifully all summer. Twelve men sent back to Nanipacna with reports reached that place to find only a deserted camp and a letter saying that the famished colony had returned to Pensacola. When Arellano wished to go to Coosa to see if it was suitable for a colony, his people mutinied. The malcontents sent a spurious order to the explorers at Coosa to return, and in November 1560, after more than a year in the interior, the little band joined the main body at Pensacola.

Two ships, which Arellano had sent home for aid, reached Mexico safely. The Viceroy immediately sent provisions for the colonists and a new leader, Angel de Villafane, to replace Arellano and to enjoy those high-sounding but, so far, empty titles bestowed upon the successive Governors of Florida.

Villafane’s orders were to move the colonists to Santa Elena. Pensacola was too far westward for Philip’s chief purpose; the most important matter was establishing a colony on the Atlantic seaboard where it could watch the French should they venture too far south of Cartier’s river. Fray Gregorio de Beteta, who had been with Fray Luis Cancer of martyr fame, accompanied Angel de Villafane in the hope that the natives of Carolina would prove less recalcitrant than those about Tampa Bay. Villafane provisioned the garrison at Pensacola and then set sail for Santa Elena. Many of his followers deserted him in Havana, but he reached the Carolina coast with the residue in May. He explored as far as Cape Hatteras but found no site he considered suitable for colonization. He then abandoned the project and returned to Espanola in July 1561. A ship was soon dispatched to remove the garrison left at Pensacola.

The failure of the Spaniards, thus far, to settle on the coast of the Atlantic mainland of North America is readily explicable. In the islands, in Mexico, and South America, the Spaniards flourished because of the precious metals and the docility of the natives. On the northern mainland, they found no mines, and the Indians would not submit to enslavement. They traversed a rich game country and great tracts of fertile soil which, later, the English settler’s rifle and plow were to make sustaining and secure to the English race. But, the Spaniards, accustomed in America to living off the supplies and labor of submissive natives, were not allured by the prospect of taming tall Creek warriors or of tilling the soil and hunting game to maintain themselves in the wilderness. They had astounding enterprise and courage for any rainbow trail that promised a pot of gold at the end of it but little for manual labor.

When news of Angel de Villafane’s failure reached Spain, King Philip decided against any further attempts to colonize Florida for the time being. He was reassured as to France because the French, as yet, had not made any firm foothold on American soil. There seemed little to alarm him in the steady increase of their fishing vessels, alongside those of Spain, in Newfoundland waters, or in the small trade in the furs the fishermen were bringing home yearly. He could not foresee that not the pot of gold but the beaver was to lead to the solution of the Northern Mystery and to spread colonies from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Moreover, though the King, where the Spaniards had failed, Frenchmen could not succeed. So, in September 1561, Philip declared about the northern coast. Interestingly, he was largely influenced by this decision by the advice of Captain Pedro Menendez de Aviles, who was very shortly to change both his mind and Philip’s. But, no doubt he relied more on the treaty signed in 1559 between himself and Henry II of France, under which France surrendered booty from Spanish ships and ports, said — perhaps somewhat extravagantly — to equal in value a third of the kingdom and, on his own marriage by proxy in the same year to the French princess Elizabeth, daughter of Catherine de’ Medici.

But, Philip’s policy of hands-off Florida was destined for a speedy reversal to meet the necessity of a new intrusion into Spanish domains. A year had not passed when Jean Ribault of Dieppe led a colony of French Huguenots to Port Royal, South Carolina, the very Santa Elena that Villafane, less than a year before, had tried to occupy for Spain. Ribault’s enterprise dismally failed, but two years later, Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France, a Huguenot, and the uncompromising foe of Spain, sent a second colony under Rene de Laudonniere. This time, a French settlement was founded, protected by Fort Caroline, on the St. John’s River, in the land of which Juan Ponce de Leon had taken solemn possession for Spain. The enthusiastic reports made by these French pioneers prove that the Spanish ran astray in the face of tales that were told in the American wilds. Jean Ribault heard of the Seven Cities of Cibola. Still, Laudonniere went him one better, for one of his scouts, while exploring the country roundabout, actually saw and conversed with men who had drunk at the Fountain of Youth and had already comfortably passed their first quarter of a thousand years.

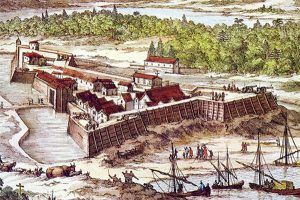

But, Laudonniere’s artistic sense did not fit him to lead a colony made up chiefly of ex-soldiers, including both Huguenots and Catholics, who had so recently been in armed strife on their home soil. Men who tilled the ground had been omitted from the roster; the artisans could not turn farmers on the instant, and the soldiers were not inclined to beat their swords into plowshares so long as Spanish treasure ships sailed the Bahama Channel. Laudonniere offended the Indians nearby by trying to make friends with their foes and forcing them to set free some captives, and so, was presently in straits for food. Some of his men mutinied, seized two vessels, and went out on a pirate raid. One of their ships, with 33 men aboard, was captured by the Spaniards, and the men were hanged — in return for their seizure of a Spanish ship and the killing of a judge who was aboard. The other ship returned to Fort Caroline, and Laudonniere had the ringleaders executed.

Only ten days’ food supply was left when, like gulls rising against the sun, four strange sails fluttered over the horizon one morning. Instead of Spaniards bent on war, the visitor, who sailed his fleet into the river’s mouth, was the English sea dog, John Hawkins. Master Hawkins had been marketing a cargo of Guinea Coast blacks in the islands where, by a suggestive display of swords and muzzles, he had forced the Spaniards to meet his prices and to give him a “testimonial of his good behavior” while in their ports.

Hawkins fed and wined the French settlers and offered to carry them away safely to French soil. But Laudonniere, not knowing whether France was at peace or war with England, was afraid to trust the generous pirate. So far from resenting Laudonniere’s suspicions, Hawkins, no doubt thinking that, in like circumstances, he would be equally cautious, agreed to sell a vessel at whatever price the Frenchman should name. And, he threw into the bargain provisions and 50 pairs of shoes so that Laudonniere, in his memoir, descants much upon this “good and charitable man.”

Grave reports of Laudonniere’s mismanagement reached Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, who sent Jean Ribault again to take command. With his son Jacques, Ribault and 300 more colonists, chiefly soldiers, set sail on May 23, 1565. On the eve of the departure, Ribault received a letter from Coligny, saying that a certain Don Pedro Menendez was leaving Spain for the coast of “New France” — such the French declared to be the name of the coast south of the St. Lawrence River. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny sternly counseled Ribault not to suffer Menendez to “encroach” upon him “no more than he would that you should encroach upon him.”

If the settlement at Port Royal had been a disquieting intrusion, Fort Caroline, under the very nose of Havana and on the path of the treasure fleets, was an imminent menace to New Spain. Its import was plainly stated in the reports to Philip from Mexico. “The sum of all that can be said in the matter is that they put the Indies in a crucible, for we are compelled to pass in front of their port, and with the greatest ease, they can sally out with their armadas to seek us, and easily return home when it suits them.” In urging action before Admiral Coligny could send Ribault to relieve the colonists, the same report continued: “seeing that they are Lutherans … it is not needful to leave a man alive, but, to inflict an exemplary punishment, that they may remember it forever.”

While Philip’s envoy to France had protested French depredations, the matter had not been pushed to a consequence because Philip desired to enlist the aid of Queen Catherine de’ Medici. Catherine was also forced to temporize. She needed Philip’s support to maintain her position of power in France between Catholic Leaguer and Huguenot, but she dared not, for his friendship, go so far as to interfere with Coligny’s designs on Florida, lest even the French Catholics turn against her; for they too had caught the Admiral’s vision of a France once more great, rich, and glorious. It suited her, therefore, to make the answer that the French ships were bound for a country discovered by France and known as the Terre des Bretons and would, in no way, molest the territories of Spain. Jean Ribault reached Fort Caroline while Laudonniere and his men were still there. With the arrival of his ships, bringing 300 more colonists, evacuation plans were abandoned.

To expel and castigate the French and to plant his own power solidly in Florida, Philip had finally picked a man who would not fail. Menendez was already a sea soldier of note and had rendered distinguished services to the Crown. He was a nobleman of the Asturias, where “the earth and sky bear men who are honest, not tricksters, truthful, not babblers, most faithful to the King, generous, friendly, light-hearted, and merry, daring, and warlike.” During the recent wars, as a naval officer, he had fought the French, and later, off his home coasts and off the Canaries, he had defeated French pirate ships.

Menendez’s contract was a typical conquistador’s agreement. His chance to serve the King was a certainty. His profits were a gamble. The title of Adelantado of Florida granted him was made hereditary. His salary of two thousand ducats yearly was to be collected from rents and products of the colony. He was given a grant of land 25 miles square, with the title of Marquis, and two fisheries — one of the pearls — wherever he should select them. He was to have a few ships of his own to trade with some of the islands and was absolved from certain import and export duties, and for five years, he was to retain whatever spoils he found aboard the pirate vessels he captured. Apart from a loan from Philip of 15,000 ducats, which he bound himself to repay, he was to bear all the expenses of the venture — about $1,800,000. Besides the San Pelayo of 600 tons, his fleet was to contain six sloops of 50 tons each and four smaller vessels for use in the shallow waters of Florida. His colonists numbered 500, of which 100 must be soldiers, 100 sailors, and the rest artisans, officials, and farmers, and 200 of whom must be married. He was to take four Jesuit priests and 10-12 friars. He was to parcel the land to settlers and build two towns, each to contain 100 citizens and be protected by a fort. He was also to take about 500 black slaves, half of whom were to be women. Above all, he was to see that none of his colonists were Jews or secret heretics. And he was to drive out the French settlers “by what means you see fit.” He must also make a detailed report on the Atlantic coast from the Florida Keys to Newfoundland. Menendez’s previous success as a chastiser of pirates may be indicated by his possession of nearly two million dollars to spend on this colony. When his entire company was raised, it comprised 2,646 persons, “not mendicants and vagabonds… but, of the best horsemen of Asturias, Galicia, and Vizcaya … trustworthy persons, for the security of the enterprise.”

Captain Pedro Menendez de Aviles sailed from Cadiz on July 29, 1565. In the islands, 30 of his men and three priests deserted, but neither this circumstance nor the non-arrival of half his ships, which were delayed by storms, prevented him from continuing at once for Florida. On August 28, he dropped anchor in a harbor about the mouth of a river and gave it the name of the saint on whose festival he had discovered it: Saint Augustine. Seven days later, he went up the coast, looking for the French. In the afternoon, he found four of Ribault’s ships lying outside the bar at St. John’s River. Menendez, ignoring the French fire, which was aimed too high to do any damage, led his vessels in among the foes.

“Gentlemen, from where does this fleet come?” he demanded, “very courteously.”

“From France,” came the answer from Ribault’s flagship.

“What are you doing here?”

“Bringing infantry, artillery, and supplies for a fort which the King of France has in this country and for others which he is going to make.”

“Are you Catholics or Lutherans?”

“Lutherans and our general is Jean Ribault.”

In answer to questions from the French ship, Menendez replied: “I am the General; my name is Pedro Menendez de Aviles. This is the armada of the King of Spain, who has sent me to this coast and country to burn and hang the Lutheran French who should be found there, and in the morning, I will board your ships, and if I find any Catholics they will be well treated.”

In the pause that followed this exchange of courtesies — “a stillness such as I have never heard since I came to the world,” says the Spanish chaplain — the French cut their cables and, passing through the midst of the Spanish fleet, made off to sea. Pedro Menendez de Aviles gave chase. But, the French ships were too swift for him. So, at dawn, he returned to the river’s mouth. But, seeing the three other French vessels within the bar and soldiers massed on the bank, he withdrew and sailed back to St. Augustine.

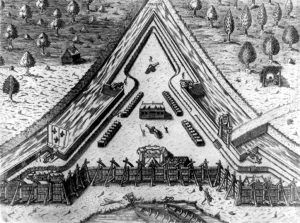

Here, he began fortifying a large Indian house, dug a trench about it, and bulwarked it with logs and earth. This converted Indian dwelling was the beginning of the settlement of St. Augustine. With the work finished and the last of the colonists and supplies landed, Menendez took formal possession. From a distance, the French ships watched the landing of the Spanish troops, then made off to St. John’s River. On arrival at Fort Caroline, Jean Ribault gathered his vessels together — except his son’s, which had not returned — and, taking aboard 400 soldiers, set out again to attack St. Augustine. He left only 240 men at Fort Caroline, many of whom were ill. His plans were made against the advice of Laudonniere, left in command of the fort, who urged the danger of his situation should contrary winds drive Ribault’s ships out to sea and the Spaniards make an attack by land. These forebodings were prophetic. A terrible wind arose, which blew for days. And, Menendez, guided by Indians and a French prisoner he had picked up in the islands, marched overland upon Fort Caroline.

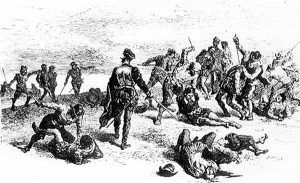

On September 20, just before daybreak, Menendez reached the fort. Most of the men inside were asleep. The trumpeter on the bastion had barely sounded the alarm before the Spaniards were inside the walls. The French had no time to don clothes or armor. In their shirts or naked, they seized their swords and rushed out into the gray light of the court. Within an hour, 132 French had been killed, and half a dozen men and fifty women and children were captured. The remaining French, many wounded, escaped to the woods; among them was Laudonniere. It was not a fight but a massacre. Even the very sick were dragged out and slain. One woman who escaped had a dagger wound in her breast, though Menendez had given orders to spare the women and children, fearing “that our Lord would punish me if I acted towards them with cruelty.”

Twenty-six French, including Laudonniere, were rescued by the ships of Jacques Ribault and ultimately reached France. Some twenty more, too severely damaged to travel fast, were discovered by the men sent out by Pedro Captain Menendez de Aviles to beat the brush thoroughly for fugitives and run through with swords. One lone man, a belated Cabeza de Vara, traveled across the country from tribe to tribe and came out at Panuco. After a brief rest at the post, which he rechristened Fort San Mateo, Menendez marched swiftly back to St. Augustine. He learned that 140 men from two French ships wrecked by the storm were nearby. They had lost 200 of their comrades, drowned, killed, or captured by Indians; they were destitute. Menendez made a quick march to the spot. When the castaways pleaded that their lives be spared until the arrival of a French ship to take them home, Menendez answered that he was “waging a war of fire and blood against all who came to settle these parts and plant in them their evil Lutheran sect…

For this reason, I would not grant them a safe passage but would sooner follow them by sea and land until I had taken their lives.” An offer of 5,000 ducats for their lives met with the ambiguous reply that mercy would be shown for its own sake and not for price. So, read the Spanish reports of this event. French reports state that Menendez induced the 140 men to surrender themselves, their arms, and ammunition without a blow and gave his oath to spare their lives and to send them to France.

The chaplain discovered ten Catholics among them, and these were set apart. The remaining 130 men were given food and drink and told that — as a precaution because of their numbers — they must consent to have their hands bound behind them on the march to St. Augustine. Captain Menendez de Aviles ordered a meal prepared for the prisoners, gave his final instructions regarding them to the officers in charge, and went on ahead. A gunshot’s distance off, beyond a hummock, he paused long enough to draw a line with his spear in the white sand of the flat. Then he went on. The heavy dusk from the sea was massing swiftly behind the Frenchmen, and the last faint flush of the afterglow was fading from the western sky when they came up alongside the spear line in the sand. There, the Spaniards fell upon them, slew, and decapitated them. The place is still known as Las Matanzas (The Massacre).

Shortly after Captain Menendez de Aviles had reached St. Augustine, Indians informed him that Jean Ribault and 200 men were at Matanzas, having been cut off there, as the other Frenchmen had been, by the inlet, as they were attempting to reach Fort Caroline by land. Menendez set out immediately. Once more, the same ceremonies repeated, and Ribault and his 200 were induced to surrender. When, with their hands bound, they were halted at the spear line, now more clearly indicated by the heap of corpses along it, they were asked: “Are you Catholics or Lutherans, and are there any who wish to confess?” Seventeen Catholics were found and set aside. But, Ribault, the staunch Huguenot mariner of Dieppe, had been too long familiar with the menace of death to recant because a dagger was poised over his entrails. He answered for himself and the rest, saying that a score of years of life was a small matter, for “from the earth, we came, and unto the earth, we return.” Then he recited passages from Psalms. One of Menendez’s captains thrust his dagger into Ribault’s bowels, and Meras, the adelantado’s brother-in-law, drove his pike through his breast; then they hacked off his head. “I put Jean Ribault and all the rest of them to the knife,” Captain Menendez de Aviles wrote to Philip, “judging it to be necessary to the service of the Lord Our God and Your Majesty. And, I think it a great fortune that this man be dead … he could do more in one year than another in ten, for he was the most experienced sailor and corsair known, very skillful in this navigation of the Indies and the Florida Coast.”

There were some among his officers at St. Augustine and among the nobility in Spain who condemned Menendez for his cruelty and for slaying the captives after having given his oath for their safety. But, Barrientos, a contemporary historian, holds that he was “very merciful” to them, for he could “legally have burnt them alive . . . He killed them, I think, rather by divine inspiration.” And, Philip’s comment, scribbled by his pen on the back of Menendez’s dispatch, was: “As to those he has killed, he has done well, and as to those he has saved, they shall be sent to the galleys… We hold that we have been well served.”

The name of Captain Menendez de Aviles is popularly associated in America almost solely with this inhuman episode. But, the expulsion of the French was only an incident in work covering nearly ten years. During that time, Menendez proved himself to be an able and constructive administrator and a vigorous soldier and laid the foundation of a Spanish colony on the northern mainland that endured. Menendez was a dreamer, as are all men of vision, and he pictured a great future for his Florida — which, to him, meant the whole of northeastern America. He would fortify the Peninsula to prevent any foreigner from gaining control of the Bahama Channel, that highway of the precious treasure fleets; he would ascend the Atlantic coast and occupy Santa Elena, where the French had intruded, and the Bay of Santa Maria (Chesapeake Bay), for, since one of its arms was perhaps the long-sought northern passage, the bay might prove to be the highway to the Moluccas, much endangered now by the activities of the French. It was hoped that the other extremity on the Pacific might be discovered by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, who, shortly before, had started on his way to conquer the Philippine Islands. This was accomplished, then away with France and her St. Lawrence River, which Jacques Cartier and La Rocque de Roberval had found untenable. To approach Mexico, Menendez would occupy Apalachee Bay and plant a colony at Coosa, “at the foot of the mountains which come from the mines of Zacatecas and San Martin,” where Francisco de Ibarra was engaged in carving out the Kingdom of New Biscay. Finally, Menendez had great hopes of economic prosperity, for silkworms, vineyards, mines pearls, sugar plantations, wheat and rice fields, herds of cattle, salines, ship timber, and pitch would make Florida not only self-supporting but richer “than New Spain or even Peru.”

Vast and unified in vision were these contemporaneous projects of King Philip and his men, embracing the two oceans and reaching from Spain to the Philippine Islands. The tasks of Captain Menendez de Aviles in La Florida, Ibarra in New Biscay, and Legaspi in the Philippines were all but parts of one great whole. Florida said Menendez, with a twentieth-century contempt for distance and a Spanish disregard of time, “is but a suburb of Spain, for it does not take more than forty days sailing to come here, and usually as many more to return.”

Within two years, Menendez had established a line of posts between Tampa Bay and Santa Elena (Port Royal) and had attempted to colonize Virginia. But, this work had not been done without setbacks. Disease and the adventurer’s dislike of manual labor — the same enemies that so nearly wrecked the English settlement at Jamestown several decades later — played their part in hampering the growth of the Florida settlements.

When the colonies might perhaps have been, to a degree, self-supporting, it was still necessary to import all their supplies. Over 100 colonists died at St. Augustine and San Mateo (Fort Caroline); the attitude of others was fairly expressed in the statement of some deserters, that they had not come there to plow and plant but to find riches and since no riches were to be found, they would no longer live in Florida “like beasts.” From the principal settlements, over 300 men absconded; 130 belonging to St. Augustine seized a supply ship and made off in it. But, Menendez’s forces were strengthened by over 1,000 colonists from Spain. The foothold in Florida had been won.

Meanwhile, Captain Menendez de Aviles had turned to inland exploration. While at Santa Elena in 1566, he sent Juan Pardo with 25 men “to discover and conquer the interior country from there to Mexico.” Menendez aimed to join hands with the advance guard of pioneers in New Biscay. Going northward through Orista at forty leagues, Pardo struck the Cambahee River. Turning west, he visited Cufitachiqui, where Hernando De Soto had dallied with the “queen” a quarter century before. A few days later, he was at Juala, on a stream near the foot of the Alleghanies. He could not proceed with the mountain being covered with snow, he could not proceed, so he built a stockade called Fort San Juan and left a garrison under Sergeant Boyano. Going east to Wateree, he left a priest and four soldiers there and returned directly to Santa Elena. Thus, he extended De Soto’s work by exploring a large part of South Carolina and adding considerably to the knowledge of North Carolina.

Conversion of the natives was essential to Menendez’s scheme to pacify and hold the country. He had, as yet, no missionaries, so he detailed some of his soldiers to the work, and, in 1566, by much urging, he induced Philip to equip and send three Jesuits to Florida. The three were Father Martinez, Father Rogel, and Brother Villa-real. Their mission began in disaster. Indians killed Father Martinez, and the other two withdrew temporarily to the West Indies. On their return, Menendez established Father Rosrel with a garrison of 50 soldiers at San Antonio, on Charlotte Bay, in the territory of the cacique Carlos, and Brother Villareal, also with a garrison, at Tegesta on the Miami River mouth at Biscayne Bay.

Menendez had now established three permanent settlements on the Atlantic coast — St. Augustine and San Mateo in Florida and Santa Elena in South Carolina; and he had garrisoned forts at Guale in northern Georgia, at Tampa and Charlotte Bays on the west coast of the peninsula, and at Biscayne Bay and the St. Lucie River on the east coast. From these points, Spaniards would now command the routes of the treasure fleets from the West Indies and from Vera Cruz. He had also projected a settlement at Chesapeake Bay, which was not fated to endure.

In May 1567, after 20 months of continuous activity, Captain Menendez de Aviles went to Spain. There, he was acclaimed as a hero. Philip made him Captain-General of the West, commanding a large fleet to secure the route to the West Indies. He appointed him Governor of Cuba and created him Knight Commander of the Holy Cross of Zarza of the order of Santiago. It was said that Menendez was greatly disappointed that his reward consisted of so many sonorous words and so little substance. Menendez had reached his zenith. The story of his later successes is varied with disasters.

In France, among all parties, the news of the massacre of Ribault’s colony had kindled fury against the Spaniards. Even to Queen Catherine, in that hour of humiliation, the slaughtered men in Florida were not Huguenots but French. She rejected King Philip’s insinuating suggestions to make Admiral Coligny the scapegoat, avowed her own responsibility, and protested bitterly the arrogance and cruelty of Philip’s agent in murdering her subjects. But, her position in divided France was such that Philip had the whip hand, and he couched his answers in terms to make her feel it. She dared not go beyond high words, lest he publishes her as an enemy of her own Church and, by some sudden stroke at her or her invalid son, hasten the end at which all his intrigues in her kingdom aimed, namely, the complete subservience of France to the Spanish Crown.

Queen Catherine could not avenge the wrong, but Dominique de Gourgues could. Gourgues was an ex-soldier and a citizen of a good family; his parents were Catholics, and he is not known to have been a Protestant. He had been captured in war by the Spaniards and had been forced to serve as a galley slave. Now, to his grievance, that of his nation was added, and he chose to avenge both. It is possible that he did not have the aid of the Queen and Admiral Gaspard de Coligny in raising his expedition- ostensibly to engage in the slave trade- but it is quite probable that he did. He timed his stroke to fall during the absence of Menendez in Spain. With 180 men, he went out in August 1567 and spent the winter trading in the West Indies. Early the following year, he proceeded to Florida, landed quietly near St. John’s River, and made an alliance with Chief Saturiba, who was hostile to the Spaniards but an old friend of the French. Saturiba received him with demonstrations of joy, called his secondary chiefs to a war council, and presented Gourgues with a French lad whom his tribe had succored and concealed from the Spaniards since the time of Jean Ribault.

His force, augmented by Saturiba’s warriors, Dominique de Gourgues, marched stealthily upon San Mateo. The Spaniards in the outpost blockhouses had just dined “and were still picking their teeth” when Gourgues’ cry rang out: “Yonder are the thieves who have stolen this land from our King. Yonder are the murderers who have massacred our French. On! On! Let us avenge our King! Let us show that we are Frenchmen!”

The garrison in the first blockhouse, 60 in all, were killed or captured. The men in the second blockhouse met the same fate, and the French pushed on towards San Mateo fort itself, their fury having been increased by the sight of French cannon on the blockhouses — reminders of Fort Caroline. The Spaniards at San Mateo had received the warning. A number had made off towards St. Augustine; the remaining garrison opened artillery fire upon the French. The trees screened the Indian allies, and the Spaniards, in making a foray, were caught between the two forces. “As many as possible were taken alive by Captain Gourgues’ order to do to them what they had done to the French.” The completion of Gourgues’ revenge is thus related: “They are swung from the branches of the same trees on which they had hung the French, and in place of the inscription which Captain Menendez de Aviles had put up containing these words in Spanish, do this not as to Frenchmen but as to Lutherans, Captain Gourgues causes to be inscribed with a hot iron on a pine tablet: do this not as to Spaniards nor as to Marranos [secret Jews] but as traitors, robbers, and murderers.”

Captain Dominique de Gourgues now turned homeward. On the way, he captured three Spanish treasure ships, threw their crews overboard, and took their contents of gold, pearls, merchandise, and arms. With hideous vindictiveness on land and water, had he repaid the Spaniards for the massacre of his countrymen on Florida soil and his own degradation as a slave in their galleys on the sea. And he, too, like Menendez, stepping red-handed upon his native shores, was acclaimed as a hero.

Troubles now came fast upon the Spaniards in Florida. Indians rose and massacred the soldiers at Tampa Bay. The garrison at San Antonio was compelled by hunger and the hostility of the natives to withdraw to St. Augustine. In rapid succession, the interior posts established by Pardo and Boyano were destroyed by the Indians or abandoned to save provisions. By 1570, Indian attacks and shortage of food had forced several colonists to leave the country.

The missionaries succeeded little better than the soldiers, though Menendez sent 14 more Jesuits from Spain in 1568 under Father Juan Bautista de Segura. Father Rogel, driven from San Antonio and then from Santa Elena, returned to Havana. Father Sedeno and some five companions went to Georgia, where they labored for a year with some success.

Brother Domingo translated the catechism into the native tongue, and Brother Baez compiled a grammar, the first written in the United States. Father Rogel went to Santa Elena, where he founded a mission at Orista, some five leagues from the settlement of San Felipe. He succeeded well for several months, but finally, the Indians became hostile, and when the commander levied a tribute of provisions to feed the hungry settlers, they rebelled. Father Rogel was forced to withdraw to Havana in 1570. At about the same time and for similar reasons, the missionaries abandoned Georgia.

Though he had failed on the peninsula and the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina, Father Segura did not give up. Still, they transferred his efforts to the Chesapeake Bay, where, with six other Jesuits, he founded a mission at Axacan, perhaps on the Rappahannock River. However, within a few months, the fickle Indians turned against them and slew Segura and his entire band in 1571. On his return from Spain, Captain Menendez de Aviles went to the Chesapeake Bay and avenged the death of the missionaries by hanging eight Indians to the yardarms of his ship. After the martyrdom of Segura, the Jesuits abandoned the field of Florida for Mexico. But, in 1573, nine Franciscans began work in this unpromising territory. Others came in 1577, and in 1593, twelve more arrived under Father Juan de Silva. They set forth and founded missions along the northern coasts from their monastery at St. Augustine. Fray Pedro Chozas made broad explorations inland, and Father Pareja began his famous work on the Indian languages. By 1615, more than 20 mission stations were erected in today’s region, comprising Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Though little known, the story of these Franciscan missions is one of self-sacrifice, religious zeal, and heroism, scarcely excelled by that of the Jesuits in Canada or the Franciscans in California. It is recorded in the mute but eloquent names scattered here and there along the Atlantic coast.

In 1572, Captain Menendez de Aviles was, first of all, a seaman, and he was called home to assist King Philip in the preparation of the great Armada, which the King was slowly getting ready. But, Menendez did not live to command the Armada, for he died in 1574. His body was carried to the Church of St. Nicholas in Aviles and placed in a niche on the Gospel side of the altar. His tomb is marked with this inscription: “Here lies interred the very illustrious cavalier Menendez de Aviles, a native of this town, Adelantado of the Provinces of Florida, Commander of the Holy Cross of La Carca of the Order of Santiago and C. Gen. of the Ocean Sea and of the Catholic Armada which Lord Philip II. Assembled against England in 1574, at Santander, where he died on September 17 of the said year being fifty-five years of age.”

When Menendez returned to Spain, King Philip’s intrigues in France reached their logical culmination — in the Massacre of St. Bartholomew and the end of Admiral Coligny. Again, France was no longer a menace in the agonies of civil strife. The new shadow on his horizon was England — with her growing navy and Protestant faith; and her Queen, who was as expert a politician as any man sent by Spain to her court and more subtle than Philip himself. “A hundred thousand devils possess this woman,” the Spanish envoy wrote to his King. During the years while England, after the upheavals of Queen Mary’s reign, was becoming stable and waxing strong, Queen Elizabeth’s dexterity kept King Philip halting from any one of the deadly blows he might have struck at her. By her brilliant wit and her deception, she kept him pondering when he should have been acting. She worked upon his religious zeal and vanity by letting herself be surprised by his envoy with a crucifix in her hands or blushing with confusion over Philip’s portraits. By these and other methods, she kept him from bringing his intrigues among her Catholic subjects to a head, lessened his support of Mary Stuart, and caused him to put off his designs for her own assassination.

But this play could not go on forever. The piracies of the English sea dogs, the honoring by Elizabeth of Francis Drake on his return from looting Spanish ships and “taking possession” of the North Pacific coast as New Albion, the attempts of Raleigh and White to plant colonies in Virginia and Guiana, and later, the sacking of Santo Domingo and Cartagena and the destruction of St. Augustine by Drake, and, finally, the persecution of the Jesuits in England, at last spurred King Philip to combat. By the Pope, who had issued a Bull of Deposition against Queen Elizabeth, he had long been urged to conquer renegade England, and Mary Stuart had bequeathed her “rights” as sovereign of that kingdom. Philip had seen that his distant colonies could not be defended unless he were the sole King of the Ocean Sea.

So, the destiny of North America was decided on the North Sea in July 1588, in the defeat of the Spanish Armada by Sir Francis Drake. The mastery of the ocean passed from Spain to England. The waterways were now open for English colonists to seek those northern shores Spain had failed to occupy. In time, the sparse settlements in the Spanish province of Florida came to be hemmed in on the north by the English colonies of Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama. They stopped on the west by the French colony of Louisiana.

Jamestown, Virginia in 1607; Charleston, South Carolina in 1670; Savannah, Georgia in 1733 – thus, the English advanced relentlessly. And, in 1763, following the Seven Years’ War, in which Spain fought on the side of France, the English expelled Spain from Florida entirely. Spain’s recovery of her foothold there during the American Revolution and her struggle afterward to hold back the oncoming tide of the now independent Anglo-Americans profited her nothing in the end, for in 1819, 212 years after Jamestown, all that remained to Spain of her old province of Florida passed to the United States.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

About This Article: This article was excerpted from The Spanish Borderlands: A Chronicle of Old Florida and the Southwest, edited by Herbert Eugene Bolton, a professor at the University of Texas. This book was in a fifty-volume series called The Chronicles of America, published by the Yale University Press in 1918. The volumes were written by various historians of the time on topics of American History. In 1923, Yale created a series of films based on the books. Fifteen films were ultimately produced. Though the article appears here contextually the same, it is not verbatim, as it has been edited to a small extent.

Also See:

Explorers, Trappers, & Traders