“It is true that no general organization for law and order was effected on the western side of the river. But the American instinct for fair play and a hearing for everybody prevailed so that while there was no mob law, the law of self-preservation asserted itself, and the counsels of the level-headed older men prevailed. When an occasion called for action, a “high court” was convened, and woe betide the man that would undertake to defy its mandates after its deliberations were made public.”

– Ezra Meeker, recalling 1852

Given the extremes which tested overland trail emigrants to their limits, the evidence of crime among the travelers was low, but it did happen.

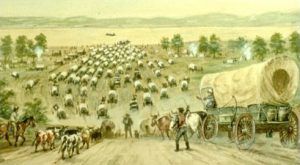

The pioneer families headed west on the Oregon–California Trail were essentially small, mobile, self-contained communities and, as such, were plagued with the same issues that found in the settlements from which they left back east. These controversies might include politics, religion, morals, family disputes, money, property, theft, and women.

But, in addition to those issues was the grueling experience of life on the trail. The pioneers faced the unforgiving elements of the weather, exhaustion, malnutrition, disease, sore muscles, and congested campsites with hundreds of strangers.

Disputes such as travel speed, treatment of animals, and route and leadership choices caused tensions to rise and were known to split more than a few parties of emigrants.

The full spectrum of human emotions often led to impatience and short tempers, which led to arguments, fights, and even murder.

“If there is any meanness in a man, it makes no difference how well he has it covered; the plains is the place that will bring it out.”

– E. W. Conyers, 1852

There were no civil laws, lawmen, or courts of law to protect those who crossed the plains. The military offered some protection near the forts but did not have jurisdiction over civilian criminal matters.

For these reasons, the better-organized wagon trains drew up a written constitution, code, resolutions, or by-laws to which the emigrants could refer when disagreements threatened to get out of hand. These regulations for conduct would be established even before they left Missouri. Part of this process was to elect a council or governing body empowered to carry out their own justice.

These regulations typically included rules for decision making, voting, camping and marching, restrictions on gambling and drinking, defense, private property rights, failing to perform duties, security for the sick or bereaved, rules for infractions, and penalties for crimes.

These were all necessary to keep the peace between the diverse groups of people living and working together for up to six months.

For minor crimes, the council would generally order only mediation. More violent crimes might include public whipping. Serious crimes such as murder, rape, and theft of horses, were addressed more formally with the emigrants choosing and judging, forming a jury, and holding a trial to the standards they were familiar with. Punishments for these serious offenses included banishment from the wagon train, hanging, and firing squad.

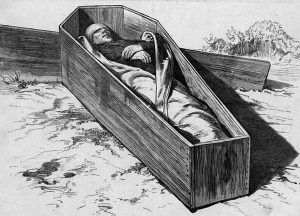

The practices of the hastily convened murder trials were pretty consistent throughout the various wagon train companies. Imitating the legal venues “back east,” after a murderer was disarmed, the wagon master, a lawyer, or a minister traveling on the train was appointed judge. The jurors were then selected from the company’s membership, who stood in a semi-circle around the accused as the rest of the pioneers looked on. A defendant’s chances of acquittal were not very good. After being found guilty, the murderer was strung up from the nearest tree. If no trees were around, crude gallows were constructed from wagon poles. Because the wagon train was anxious to move on, the murderer was usually buried in a shallow grave near his victim.

There could be no appeal from these group decisions.

“When we set foot upon the right bank of the Missouri River, we were outside the pale of civil law. We were within Indian country where no organized civil government existed. Some people and some writers have assumed that each man was a ‘law unto himself’ and free to do his own will… Nothing could be further from the facts than this assumption, as evil-doers soon found to their discomfort.”

– Ezra Meeker, 1922

Mass shootings were common along the trail, but what is rarely heard is that their fellow emigrants murdered at least 172 people on the Oregon-California Trail in the mid-1800s.

Dr. Richard L. Rieck of the Western Illinois University, who studied the pioneer diaries from 1841 through 1865, found that of these 172 murders, 89 are known by name, and another 83 are unknown.

More than half the murders occurred after passionate arguments, many of them over women and money, while nearly a fourth of the killings resulted from violent robberies. Guns and knives were the killer’s weapons of choice.

The diaries disclosed details of dozens of slayings, and bodies of obvious murder victims were occasionally found on the trail.

While most of the perpetrators were unidentified and escaped punishment, 21 reported murder trials resulted in executions on the trail.

“We tend to think of the people in the wagon trains as brave close-knit families, and the possibility of murder among this wholesome group never crosses our minds.” – Richard Rieck.

A doctor traveling from Indiana to Oregon in 1852, the peak year of western wagon travel, reported that on the overland trail, there were “not less than 50” murders as well as a large number of executions.

Diaries and historical accounts of the trail tell us about some of these many murders.

Ezra Meeker, an American pioneer who traveled the Oregon Trail by ox-drawn wagon as a young man and who would later be an influential advocate for preserving the Oregon Trail, would recall his 1852 journey:

“An incident that occurred in what is now Wyoming well up on the Sweetwater River will illustrate the spirit of determination of the sturdy men of the Plains. A murder had been committed, and it was clear the motive was robbery. The suspect had a large family and was traveling along with the moving column. A council of twelve men was called. They deliberated until the second day, meanwhile holding the murderer in their grip. What were they to do? There were a wife and four little children dependent upon this man for their lives. What would become of this man’s family if justice was Meted out to him? Soon there came an undercurrent of what might be termed ‘public opinion’ that it was probably better to forego punishment than to endanger the lives of his family by not having him look after them. But the council would not be swerved from their decision. At sundown of the third day, the criminal was hung in the presence of the whole camp – including the family – but not until ample provision had been made to ensure the safety of the family by providing a driver to finish the journey. I came so near to seeing the hanging that I did see the ends of the wagon tongues in the air and the rope dangling.”

Abigail Jane Scott traveled with her family on the Oregon Trail in 1852 when she was 17. Her mother and youngest brother died on the trail. Like many other women on the trail, she kept a diary that recorded some of the trail’s violence.

“July 15: This day, we remained in camp. We have been thrown into considerable excitement in consequence of a murder being committed in a train from Wisconsin, which is now camped one-half mile from us. The men of our train were called upon to serve as jurymen. The murder was committed on Hams fork of Green River, and the circumstances connected with it as near as I could learn was as follows: One Daniel Olmstead was taking five men across the plains, and it appears that they had not lived very agreeably together as it was proved in the trial which came off today that the five had boasted that they had their boss under their thumb and intended to keep him there. It was proved that Olmstead went out in the morning to watch his cattle, telling Sherman Dunmore to make a fire and put on the teakettle so they could have some breakfast. When he returned at breakfast time, the other men had finished their repast, and he asked where his breakfast was. Dunmore replied that if he wanted any, he might cook it himself. This was the result of much abusive language on both sides; however, Olmstead prepared his breakfast himself. Dunmore threatening in the most abusive manner to whip him. Olmstead calmly replied that if he did, he would not live long to brag about it. Upon this, he left him and went into the tent and commenced eating his breakfast, using for the purpose a small-sized butcher knife. Dunmore followed him and, jumping upon him, commenced beating him and endeavored to kick him in the face with his boots. Olmstead called upon the bystanders to take him off, saying at the same time that he had a knife. As no one interfered, he stabbed him in the lower part of the chest. Upon this, Dunmore started back and exclaimed that he was stabbed. He fell, and in twenty minutes was a corpse. The jury, after an impartial investigation of the tragical affair brought in a verdict to this effect: That the wound was made by the knife of Olmstead caused the death of the said Dunmore and that the same was inflicted by the aforesaid Olmstead in self-defense.”

“June 30: We passed today seven graves. Two were placed tolerably near each other one bearing the inscription ‘Charles Botsford murdered June 28, 1852. The murderer lies in the next grave’. The other bears the inscription of ‘Horace Dolley hung June 29, 1852″. It appears Dolley had contracted a grudge towards Botsford with regard to some little difficulty between them–had persuaded him to accompany him in an excursion and while alone with him, he dealt the blow at which humanity would at any time recoil. Vengeance however, quickly followed him, and he was doomed to the penalty which his conduct so completely deserved.”

The Cornoyer and Moreland family diaries told more about the murderer’s trial and execution. Two respected men were chosen to serve – a judge and a sheriff, who chose a 12-man jury. After the jury had heard the evidence, they returned 20 minutes later with a guilty verdict. Afterward, a crude scaffold was made by pushing two wagons together, their tongues raised high and tied together. The emigrants then looped a noose around Dolley’s neck, and he was pushed off the wagon seat as the wagon train members looked on.

Other briefer accounts of murders were also recorded:

“Found here a company that got into a fight among themselves. Burnt fragments of wagons, stoves, axes, etc., with a great quantity of harness cut to pieces; and with a quantity of torn shirts, coats, hats all besmeared by blood.” – James Evans, 1850

“Young shot Scott dead. The company had a trial and found him guilty. They gave him a choice to be hung or shot. He preferred being shot, and was forthwith.” – Charles Gould, 1849

Gravesites were often marked with the names of the murderer and the murdered, providing some insight. One of these was aboard at the north fork of the Humboldt River in 1849 that read, “Samuel A. Fitzsimmons, died of a wound inflicted by a bowie knife in the hands of James Remington, on August 25, 1849.”

On occasion, the fate of the murderer was recorded:

“At Goose Creek Mountains entering Nevada in 1859, emigrants saw the grave of Joseph Selleck, who was “executed for the murder of W. Humble.”

One murder story tells of a disagreeable old man named John Smith who was with a wagon train company that pulled out of St. Joseph, Missouri in 1852. Before the train was barely out of the gate, he cursed the others because they raised dust.

Early in the trip, a young boy was orphaned and unfortunately taken in by Smith. No sooner had the old man taken him in that he began to complain about the boy stating that the lad was depleting his stock of rations and could do nothing right.

Belittling the boy constantly, a train member advised Smith to change his ways, but the old man stated he would do whatever he pleased. As the journey progressed, the friction between the two became worse. On one occasion, when a wheel came off the wagon, Smith flew into a rage, accusing the boy of causing it. Smith was later heard to have said; I’ll fix him.”

The next day Smith took the boy hunting but returned without him. When the emigrants could not find the boy, Smith was tried for murder, found guilty, and hanged.

“If a man is predisposed to be quarrelsome, obstinate, or selfish, from his natural constitution, these repulsive traits are certain to be developed in a journey over the plains. The trip is a sort of a magic mirror and exposes every man’s qualities of heart connected with it, vicious or amiable.”

– Edwin Bryant

In the pioneer journals, homicides spiked in frequency as the Continental Divide drew near. The accumulated frustrations of the trail after 800 miles frequently caused trail members to lash out.

Devil’s Gate, Wyoming on the Oregon Trail

Several ram-shackle saloons existed at busy pioneer stops like Devil’s Gate and the old Green River Rendezvous country of Wyoming. With tensions already running high, alcohol made it worse, and there were several gunfights over women, horses, and general competitiveness.

John Clark, a Virginia pioneer who had caught the gold fever in 1852, traveled the Mississippi River system from Cincinnati, Ohio to St. Joseph, Missouri, where he disembarked on a wagon train headed to California. He would report that a pioneer got into a fight with his wagon driver at Devil’s Gate and shot and killed him. The man was “tried and hung on our old wagon at sundown.”

It was often difficult to sort out the cattle’s ownership at the confusing Sweetwater fords, which caused several shooting conflicts.

At the Mormon Ferry Crossing at Casper, Wyoming, the traffic backups often stretched east for miles, and armed road rage incidents often led to fatalities.

In June 1852, a Wisconsin pioneer named Polly Coon passed a lone tree along the Sweetwater River with an inscription carved on the trunk indicating the graves of a “Man, Woman & Boy” found with their throats cut, the murder or murderers unknown. The next day her train arrived at a grove of trees where a man had just been hanged for shooting his brother-in-law.

John Snyder’s murder coincides with the story of the Donner Party. By early October, a few weeks before the group became trapped, tensions were running high among the exhausted emigrants as they traveled along the Humboldt River near present-day Golconda, Nevada.

On October 5, the simmering feelings of frustration and anger erupted, and traveler James Reed killed wagon driver John Snyder.

John Snyder, a hired teamster and a well-liked party member was driving a wagon for the Graves family. While driving his wagon up a steep, sandy slope, the young teamster began to beat his oxen with his whip. Reed intervened, the two exchanged some harsh words, and Snyder’s frustration turned Reed. With the butt of his whip, he slashed Reed’s forehead.

James Reed pulled out a large hunting knife and stabbed Snyder in the chest, killing him.

Reed faced a hanging but was instead banished from the wagon train and forced to leave his wife and children behind.

Lucky for him, he missed the bad weather that trapped the rest of the Donner Party and raced toward Sutter’s Fort. Three weeks later, he led one of the rescue parties and was reunited with his family.

Another story tells of one wagon train that found justice in another way. Of the members was a grumpy old man that seemingly found fault with everything. He especially had low regard for Indians and disliked it when the train members offered cheerful greetings, stating, “The only way to treat an Indian is to shoot first and ask if he is a friendly later on.”

When the emigrant train arrived on the Platte River’s upper reaches, the pioneers enlisted the services of an Indian to guide them. This enraged the grumpy old man, who soon picked a fight with the guide. That evening a single rifle shot was heard, and upon investigation, the body of the Indian was discovered at the edge of the camp, and the grumpy old man was missing.

Though some train members wanted to bury the Indian and quickly continue, others felt his tribe would come looking for him and assume the worst. The pioneers decided that one man should return to the Indian village to explain the circumstances. Straws were drawn, and the one with the shortest stick rode east with the body of the dead Indian while the wagon train continued westward.

After the man with the short straw had explained the situation, he freely left the Indian camp. However, he was followed by a group of Indians, who stayed with him until they reached the point where their Indian guide had been killed.

Here, the warriors broke away from the Oregon Trail and began searching for the man who had killed the guide. Before long, a shot was fired. The Indians had found the grumpy old man.

Only one man was murdered on the trail. Ephraim Brown lies in a grave with a known location. From Missouri, Brown, a leading figure on a wagon train bound for California, was killed near South Pass, Wyoming in 1857 in what appears to have been a bitter family dispute.

However, violence was not limited to murder.

In 1849 while a wagon company was traveling to Utah, William Appleby described an event when the driver of Sayres wagon got into a dispute with Mrs. Sayres. When her husband, Edward Sayres, was absent, an argument between the driver and Mrs. Sayres erupted regarding driving the team. As the debate became more heated, the driver called the woman some base and vile epithets, causing her to retaliate by using her whip on him. He then struck her and blacked one of her eyes.

In an 1848 company, Oliver Huntington recorded a spousal whipping:

“We were then 380½ miles from Winter Quarters… All the camps had got along well and with few accidents. Three had been run over in our camp, and one wagon turned over, which was brother Gates. He blamed his women severely for it, and what mortified him worse than all, it disclosed a bottle of wine; before unknown. The wagon turned square bottom side up, no one in it. That night he quarreled with his wife and whipped her. The guard about 11 o’clock saw it, and when the hour came to cry, he loudly cried 11 o’clock, all is well, and Gates is quarreling with his wife like hell.”

Spousal abuse was not exceptional in those days, given women’s general treatment in the 19th century. While legal authorities prosecuted and newspapers condemned the abuse of women, much went unreported.

One extreme form of antisocial behavior among California and Oregon-bound companies members was the abandonment of individuals on the trail. This cruelty was often a death sentence. On one occasion, a young girl and her brother, who were ill from cholera, were abandoned in their wagon on the trail after their parents died. The thoughtless company moved on, taking the family’s oxen with them.

However, a passing company would be the children’s salvation. Two passing doctors prescribed medicine, and a Missouri group volunteered to take care of the orphans for the rest of the trip.

In another instance, in 1850, a company found an abandoned mother and her young daughter about 70 miles west of Salt Lake City, Utah. Two kindly westbound travelers escorted them back to the Mormon center and then turned around and retraced their steps toward California.

The trail had left another 1850 gold seeker after he was accidentally shot by one of his company. A passing physician attended to him, and westbound overlanders contributed money for his continuing care.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

Danger and Hardship on the Oregon Trail

Eye Witness Accounts on the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Sources:

Crime, Justice, and Retribution in the American West, 1850-1900; McFarland, 2017

Buck, Rinker; The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey, Simon & Schuster, 2016

Bureau of Land Management

BYU Scholars Archive

Colorado Notary Blog

Goeres-Gardner, Diane L.; Necktie Parties: A History of Legal Executions in Oregon, 1851-1905, Caxton Press, 2005

Meeker, Ezra; Ox-team Days on the Oregon Trail; Yonkers on Hudson, New York, 1922

Tahoetopia

Steber, Rick; Oregon Trail: Tales of the Wild West, Bonanza Publishing, 1986

Weekly World News, March 4, 1997