“We have not moved today. Our sick ones not able to go. The sickness on the road is alarming – most all proves fatal.” – Lydian Allen Rudd, 1852.

Healthcare in the frontier was an imperfect science in the mid-19th century, and mortality rates were lamentably high. Many children arrived at the trail’s end with fewer parents or siblings than they left home with.

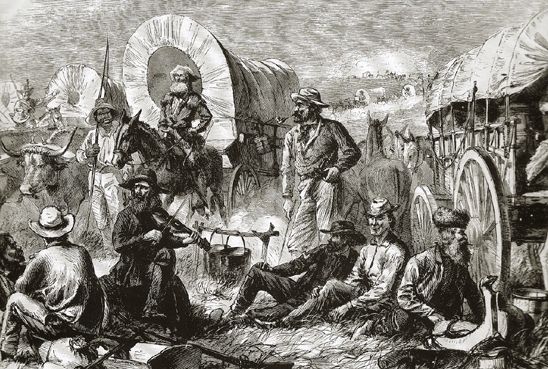

The number one killer on the trails, by a wide margin, was disease and serious illnesses, which caused the deaths of nine out of ten pioneers. The hardships of weather, limited diet, and exhaustion made travelers very vulnerable to infectious diseases such as cholera, flu, dysentery, measles, mumps, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever which could spread quickly through an entire wagon camp.

Many pioneers who headed west in the 19th Century hoped to leave behind the disease and contamination of the Eastern cities. They expected to find an environment of clean air and water; however, it was these very emigrants that, instead, changed the environment of the West, bringing with them bacteria and viruses.

These epidemics wrought turmoil along the overland trails, affecting pioneers and Indians. The worst disease on the Oregon–California Trail was Cholera.

Cholera

Along the trails, opportunities for sanitation — bathing and laundering — were severely limited, and safe drinking water was frequently unavailable in sufficient quantities. Human and animal waste, garbage, and animal carcasses were often close to available water supplies.

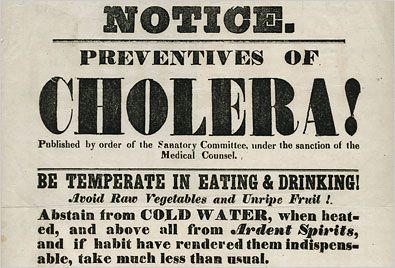

As a result, cholera, known as the “unseen destroyer” spread by contaminated water, was responsible for the most deaths on the overland trails to California and Oregon.

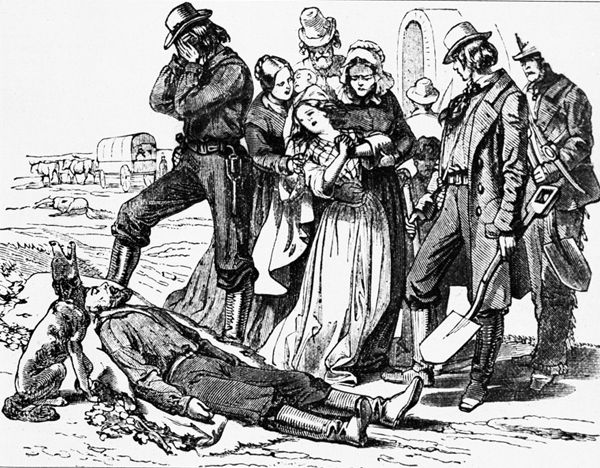

Symptoms started with a stomach ache that grew into intense pain within minutes. The disease progressed rapidly, attacking the intestinal lining and producing severe diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and cramps.

Within hours the skin was wrinkling and turning blue. With no cure or treatment for the disease, the infected emigrant usually died within 24 hours or less.

Cholera was thought to have begun in India and quickly spread worldwide along trade routes. It first appeared in America in 1832, and by the following year, it had made its way to St. Louis, Missouri, from New Orleans, Louisiana, via the Mississippi River. It then made its way westward on the riverboats along the Missouri River.

The epidemic struck St. Louis, Missouri, in early 1849, and by the end of summer, estimates of the dead ranged from 4,500 to 6,000.

During the 1849 California Gold Rush, travelers carried the bacteria along the Santa Fe Trail and other overland routes. The epidemic thrived in the unsanitary conditions along the trails, peaking in 1850 as it was stoked by the immense numbers of pioneers on the overland trails in 1849 and ’50 seeking their fortunes.

The number of trail deaths is difficult to determine; however, estimates are as high as 5,000 in 1849 alone. The losses in 1850 were more significant, prompting one Missouri newspaper to estimate that along a stretch of the Overland Trail, one person per mile died from the disease.

“The gold rush was to the cholera-like wind to fire.” – George Groh, historian

Thousands of travelers on the combined California, Oregon, and Mormon Trails succumbed to cholera between 1849 and 1855. Most were buried in unmarked graves in Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Although also considered part of the Mormon Trail, the grave of Rebecca Winters is one of the few marked ones left.

The disease was particularly deadly at the frontier outposts. In the summer of 1855, cholera struck Fort Riley, Kansas, killing the commanding officer, Major E. A. Ogden, along with about 70 other people.

Along the Platte River in Nebraska and Wyoming was the site of the highest infection rate during these years. Because of the Platte’s brackish water, the preferred camping spots were along one of the many freshwater streams draining into the Platte. With hundred utilizing the streams for bathing and drinking water, the streams became cholera breeding grounds.

The dead sometimes lay in rows of 50 or more.

Fortunately, once the emigrants were past Fort Laramie, Wyoming, they were largely safe from cholera at the higher elevations.

“People were continually hurrying past us in their desperate haste to escape the dreadful epidemic.”

– Ezra Meeker, speaking of cholera on the trail, 1852.

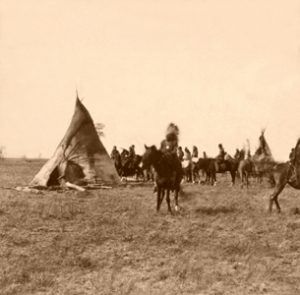

Nomadic Indian tribes also suffered the same conditions as the western-bound pioneers. As many as one-half of the Pawnee and two-thirds of the Southern Cheyenne died of cholera between 1849 and 1852. Reports among the Comanche state that survivors lacked the strength to bury hundreds of dead. Arapaho legends tell of several people who committed suicide rather than face the dreaded sickness.

The best treatment for cholera infections was unknown at the time of these outbreaks. Medical practitioners could do little to treat the pioneers except for prescribing camphor and laudanum, which could relieve the pain but did nothing to cure the disease.

The sudden, explosive nature of cholera epidemics horrified white physicians and native healers alike in their attempts to combat the disease. During the 1849–1852 epidemics, a frontier doctor named Andrew Still commented on local treatments at a Shawnee Indian Mission in Kansas:

“The Indian’s treatment for cholera was not much more ridiculous than are some of the treatments of some of the so-called doctors of medicine. They dug two holes in the ground, about twenty inches apart. The patient lay stretched over the two—vomit in one hole and purge in the other, and died stretched over the two, thus prepared, with a blanket thrown over him. Here I witnessed cramps which go with cholera dislocate hips and turn legs out from the body. I sometimes had to force the hips back to get the corpse in the coffin.”

Other Diseases

Western-bound pioneers also contended with many other ailments, including malaria, tuberculosis, measles, scarlet fever, mumps, influenza, whooping cough, and more.

In rare instances, the pioneers were near a military base and could seek help from the post-surgeon. Regardless of the complaints, these doctors, when they could be found, frequently prescribed mercury and calomel (a laxative) in the hope of purging infectious matter.

More often, the pioneers utilized home remedies or depended upon anyone in the wagon train who had even the slightest medical knowledge, such as animal birthing or bone setting.

Diphtheria – Though generally thought of as a childhood disease, diphtheria also infected adults. The disease was most often spread by contaminated food or water. It was most likely to strike any group exposed to changes in their living habits, especially if accompanied by unsanitary conditions. It was a particularly painful version of diarrhea. Although seldom fatal, it could be very dangerous for the young and elderly. Its mortality rate was 5-10%, but children under five and the elderly were more vulnerable. There was no real medical treatment for diphtheria on the trail, and treatment was generally limited to rest and fluids. However, castor oil was used to treat dysentery and other bowel disorders. It was the greatest killer of children along the Oregon Trail.

Dysentery – A type of gastroenteritis that results in diarrhea with blood. Other symptoms may include fever, and abdominal pain. Like cholera and Typhoid fever, dysentery is contracted when people consume food or water contaminated with infected feces.

“The great cause of diarrhea, which has proven to be so fatal on the road, has been occasioned in most instances by drinking water from holes dug in the river bank and along marshes. Emigrants should be very careful about this.” — Abigail Scott, June 8, 1852

Head and Body Lice – Unbelievably, this ailment sometimes killed pioneers along the trail. Very common due to the close proximity of travelers and the lack of clean bathing water and infestation of this six-legged insect often caused skin irritations that could get infected. In the most severe cases, lice can transmit the bacteria that cause typhus, which does well in crowded, unsanitary conditions.

Influenza – Often called “the grippe” in the 1800s, the flu was a feared killer for centuries. Though the mortality rate of influenza is very low today, outbreaks in the past were known to have killed up to 7-8% of the infected population.

Malaria – An aggressive and painful disease, malaria was known as “the ague” or “fever and ague” in the 1800s. It had a reputation for sudden, widespread outbreaks, often simultaneously striking down entire families and communities. Malaria is transferred to the body by a mosquito that carries the disease. It causes chills, sweats, fevers, and abdominal pain. Quinine water was used to treat malaria. Most victims survived, though some were affected by a chronic condition that caused occasional bouts of weakness, chills, and fever.

Mountain Fever – With symptoms such as intestinal discomfort, diarrhea, headache, skin rashes, respiratory distress, and fever, this ailment was usually not fatal. The diseases that fit these symptoms include Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus, typhoid fever, and scarlet fever. Quinine water was used to treat the fever.

Measles – A highly contagious viral disease, it quickly spreads person-to-person. Ravaging the United States in the 19th century, it was not measles themselves that were life-threatening, but complications like bronchitis and pneumonia that was the killer. It was more common among children but could severely affect adults.

Pneumonia – A respiratory ailment common among groups experiencing unsanitary conditions or exposure to drastic weather changes, it causes headaches, coughs, and muscle aches. Turpentine, vinegar, and whiskey were some of its treatments.

Scurvy – An aggressive and painful disease, scurvy is caused by a lack of Vitamin C in the diet. It weakens and deteriorates body conditions and can cause swelling and bleeding of the gums and internal hemorrhages.

Summer Complaint – Though widely believed to result from heat interfering with digestion, “the summer complaint” was food poisoning. The gastrointestinal infection usually presents acute diarrhea, chiefly in infants and children, especially in the summertime. Some thought it could be cured with a teaspoon of gunpowder taken with a bit of water.

Syphilis – A venereal disease, the standard treatment for centuries was mercury. This was true during the Lewis and Clark Expedition when many men were treated with a heavy dose of mercury. Miners, fur trappers, and traders engaged in sexual relations with Native Americans, increasing the possibility of both sides becoming infected with the disease. By the mid-1800s, some people practicing “medicine” often recommended arsenic as a safer alternative.

Tuberculosis – More commonly known as consumption at the time, pioneers had no effective treatments. Among them were smoking tobacco, drinking cod liver oil, and eating a thick, boiled-down onion stew.

Typhoid Fever – Typhoid fever was spread from contaminated water like many other diseases. The primary symptom was high fever and diarrhea that could last for weeks, followed by weakness and loss of appetite. Typhoid fever was highly contagious and had a mortality rate of 10-20%. The disease was prevalent in the warmer months. To treat typhoid fever, pioneers ate wild lettuce. However, this did little to cure the sickness.

Medicine and Treatments

“Passed through St. Joseph on the Missouri River. Laid in our flour, cheese, crackers, and medicine, for no one should travel this road without medicine, for they are almost sure to have the summer complaint. Each family should have a box of physicing pills, a quart of castor oil, a quart of the best rum and a large vial of peppermint essence.”

— Elizabeth Dixon Smith

Trail pioneers were encouraged to bring medical kits to treat diseases and wounds.

These kits might include pills, castor oil, rum or whiskey, peppermint oil, quinine for malaria, hartshorn for snakebite, citric acid for scurvy, opium, laudanum, morphine, calomel, and tincture of camphor.

Some travelers carried books that were popular home remedy references, such as The Family Nurse, Gunn’s Domestic Medicine, and the Family Hand Book.

Sometimes a wagon train caravan might include a doctor. However, by the mid-1800s, many people had learned to distrust them. At that time, anyone could put up a sign and call themselves a doctor, and many unknowledgeable and unprofessional people did just that. It soon became widely known that these medical professionals had no real idea of what they were doing to cure disease. It had become so widely known that several states had stopped certifying and licensing doctors.

One of the biggest problems is that many doctors, having no knowledge of germs, unknowingly infected their patients as they did not change clothes, clean their instruments, or even wash their hands after treating one patient and before moving on to another.

Even well-trained doctors were often powerless in the face of disease, often dosing their patients with purgatives and emetics, believing whatever the cause of illness, it could be forced out through the gut.

Adding insult to injury, these practitioners rarely had “real” surgical instruments on the trail, instead using common butcher knives, carpenters’ handsaws, and shoemaker awls.

Emigrants reported numerous “doctor disaster” accounts on the trail. One terrible account was documented in Edward Bryant’s What I Saw in California, published in 1848.

“A boy, eight or nine years of age, had had his leg crushed by falling from the tongue of the wagon and being run over by its wheels… When I reached the tent of the unfortunate family to which the boy belonged, I found him stretched out upon a bench made of plank, ready for the operation which they expected I would perform. I soon learned…that the accident occasioning the fracture had occurred nine days previously. That a person professing to be a doctor had wrapped some linen loosely about the leg and made a sort of trough, or plank box, in which it had been confined. In this condition, the child remained without any dressing of his wounded limb until last night, when he called to his mother that he could feel worms crawling in his leg!… An examination of the wound for the first time was made, and it was discovered that gangrene had taken place, and the limb of the child was swarming with maggots!… I made an examination… The limb had been badly fractured and had never been bandaged; and from neglect, gangrene had supervened; the child’s leg from his foot to his knee was in a state of purification.”

In the end, the boy died when his leg was amputated with a butcher knife and a handsaw.

More often, pioneers relied on the gentler and more familiar “granny medicine,” practiced by women on the trail. These folk healers relied on herbal medicine, and remedies were handed down from generation to generation.

Though sometimes successful, most of the time, their treatments were no more effective than the “doctors.” Some of these practices included using peppermint oil to treat aches and pains because it causes a sensation of warmth when applied to the skin. Asparagus was widely thought to be good for the kidneys because it makes urine smell odd. Snakebites were often treated with extracts from plants with long, stringy roots that looked snake-like.

Thousands of pioneers died of these various diseases along the trails. Sometimes they received a proper memorial and burial, but wagon trains were in a hurry and didn’t have the time to stop for an elaborate funeral. As the wagon trains moved further west, the burials got shorter and shorter as more and more people died.

Sometimes the terminally ill were even abandoned on the side of the trail, where they would eventually die alone.

Thousands of anonymous, unmarked graves remain along the trails as a testimony to the unhealthy nature of life in the era of westward expansion.

“Passed six fresh graves!… Oh, ’tis a hard thing to die far from friends and home—to be buried in a hastily dug grave without shroud or coffin—the clods filled in and then deserted, perhaps to be food for wolves…” Esther McMillan Hanna, 1852

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Adventures and Tragedies on the Overland Trail

Danger and Hardship on the Oregon Trail

California Trail – Rush to Gold

Ephraim Brown – Murdered on the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Sources:

Encyclopedia.com

Historic Oregon City

Kansapedia

National Park Association

Oregon-California Trail Association

Oregon Trail 101

Oregon Trail R U

Wikipedia

Another fun video from our friends at Arizona Ghostriders.