“To enjoy such a trip… a man must be able to endure heat like a Salamander, mud, and water like a muskrat, dust like a toad, and labor like a jackass. He must learn to eat with his unwashed fingers, drink out of the same vessel as his mules, sleep on the ground when it rains, share his blanket with vermin, and have patience with mosquitos. He must cease to think, except of where he may find grass and water and a good camping place. It is hardship without glory.” — Anonymous Settler writing in the St. Joseph, Missouri Gazette

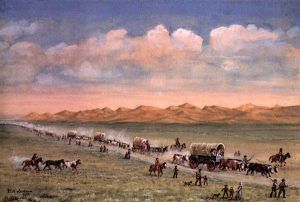

Though 19th-century settlers and much of written history look at the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail as romantic, almost one in ten who embarked on the trail didn’t survive. The Oregon Trail is this nation’s longest graveyard. Of the estimated 350,000 who started the journey, the trail claimed as many as 30,000 victims or an average of 10-15 deaths per mile.

The leading causes of deaths along the Oregon/California Trail from 1841 to 1869 were disease, accidents, and weather.

“We did not meet any sickness nor see any fresh graves until we came in on the road from St Joseph. From that out, there was scarcely a day, but we met six and not less than two fresh graves.”

— Elizabeth Keegan, 18

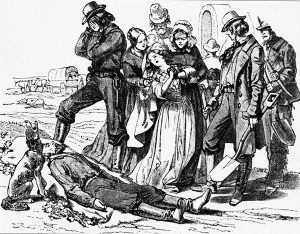

The number one killer on the Oregon Trail, by a wide margin, was disease and serious illnesses, which caused the deaths of nine out of ten pioneers who contracted them. The hardships of weather, limited diet, and exhaustion made travelers very vulnerable to infectious diseases such as cholera, flu, dysentery, measles, mumps, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever which could spread quickly through an entire wagon camp.

Opportunities for sanitation — bathing and laundering — were severely limited, and safe drinking water was frequently unavailable in sufficient quantities. Human and animal waste, garbage, and animal carcasses were often near water supplies.

As a result, cholera, spread by contaminated water, was responsible for the most deaths overall on the Oregon Trail. Cholera could attack a perfectly healthy person after breakfast, and he would be in his grave by noon. With no cure or treatment for the disease, the infected emigrant usually died within 24 hours or less. However, many would linger in misery for weeks in the bouncy wagons. Some wagon trains lost two-thirds of their people to the deadly disease in a bad year.

Food poisoning was often a problem with contaminated food, more likely among single men. Scurvy, caused by a lack of vitamin C, was also a problem. Poisoning from drinking water that was too alkaline was also common.

There was a high incidence of childbirth on the trail, and tragedy often came with the arrival of a baby. Death during childbirth was common, and infant mortality was high. Poor nutrition, lack of medical care, and poor sanitation caused many deaths.

“One woman and two men lay dead on the grass and some more ready to die. Women and children crying, some hunting medicine and none to be found. With heartfelt sorrow, we looked around for some time until I felt unwell myself. Got up and moved forward one mile so as to be out of hearing of crying and suffering.”

— Emigrant John Clark

Accidents

Numerous accidents were caused by negligence, exhaustion, guns, and animals throughout the trail’s existence.

Wagon accidents were the most common, with children and adults sometimes falling off or under wagons and being crushed under the wheels.

“A little boy fell over the front end of the wagon during our journey. In his case, the great wheels rolled over the child’s head — crushing it to pieces.”

— Edward Lenox

Crossing rivers was one of the most dangerous things that pioneers were required to do. Swollen rivers could tip over a wagon and drown both people and oxen, and valuable supplies, goods, and equipment could be lost. Sometimes this was caused by animals panicking when wading through deep, swift water. Hundreds drowned trying to cross the Kansas, North Platte, and Columbia Rivers. In 1850 alone, 37 people drowned trying to cross one particularly difficult Green River.

Those who didn’t drown were usually fleeced by a ferryman. The charge ranged up to $16, almost the price of an ox. One ferry earned $65,000 in just one summer. The emigrants complained bitterly.

Over time, this risk would be reduced as bridges and ferries became available. Even then, there were stories of rafts pitching over and improvised bridges collapsing, throwing people to their deaths.

“The ferryman allowed too many passengers to get in the boat, and the water came within two inches of the gunwale. He ordered every man to stand steady as the boat was liable to swamp. When we were nearly across the edge of the boat dipped, I thought the boat would be swamped instantly and drowned the last one of us.”

— Emigrant John B. Hill

Sometimes, alcohol played a part. On one occasion, on June 2, 1853, an inebriated emigrant misjudged the rain-swollen Buffalo Creek, drove his wagon in, and was never seen again.

Firearms were the second leading cause of emigrant injury and death. Because of the need to hunt and fear of Indian attacks, wagon trains were filled with more firepower than they would ever need. One Oregon Trail expedition had a 72-wagon train that carried 260 pistols and rifles, nearly a ton of lead, and over a thousand pounds of gunpowder. Most of the travelers had no training or experience with firearms. Consequently, countless people accidentally shot themselves or others.

The first emigrant to die due to an accidental gunshot was ironically named John Shotwell on May 13, 1841. Making matters worse was that it was self-inflicted. When he reached for the rifle, muzzle first, the firearm went off.

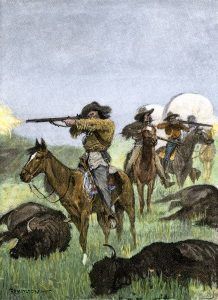

Handling domestic animals also caused accidents when travelers were thrown, kicked, or dragged by oxen, horses, and mules. Other injuries were caused by stampeding livestock. Occasionally wild animal deaths occurred when someone unwisely wandered off alone. On a few occasions, buffalo overran wagon trains causing havoc and injury.

Other emigrants suffered cuts, broken bones, burns, animal, insect, and snake bites. Others died from drowning (especially in the 1850s before there were many ferries) and quicksand.

Weather

“Such sharp and incessant flashes of lightning, such stunning and continuous thunder, I had never known before. The woods were completely obscured by the diagonal sheets of rain that fell with a heavy roar and rose in spray from the ground. The storm ceased as suddenly as it began. The thunder here is not like the tame thunder of the Atlantic coast. Bursting with a terrific crash directly above our heads, it roared over the boundless waste of the prairie, seeming to roll around the whole circle of the firmament with a peculiar and awful reverberation. The lightning flashed all night.”

— Francis Parkman, 1846

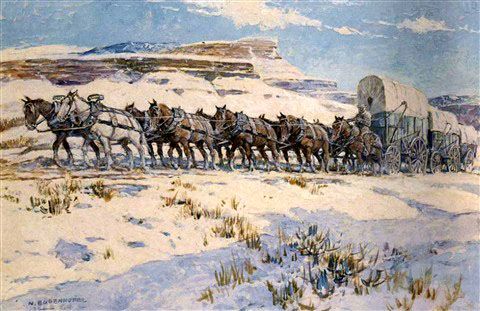

Weather-related dangers included thunderstorms, lethally large hailstones, lightning, tornadoes, grass fires, and high winds. Lightning strikes killed a half-dozen emigrants; many others were injured by hail the size of apples. There would be significant snowstorms and severe cold in the Rocky Mountains, causing frostbite and death by freezing.

The intense heat caused the wood to shrink on the prairies, and wagon wheels had to be soaked in rivers at night to keep their iron rims from rolling off during the day. The dust on the trail itself could be two or three inches deep and as fine as flour. Emigrant’s lips blistered and split in the dry air, and their only remedy was to rub axle grease on them. Numerous pioneers died from exposure.

American Indians were usually among the least of the emigrants’ problems, though the overlanders certainly thought otherwise at the time. Most Indians were peaceful and often helped the emigrants in various ways. Mostly, the Indians traded with the emigrants. Fresher or different foods to vary their diet and moccasins to replace worn-out shoes and boots were exchanged for articles of clothing and trade goods brought for just that purpose. Other help was more direct. Before white men set up ferries and bridges to cross treacherous rivers, Indians made ferries out of canoes to take wagons and people across.

Tales of hostile encounters far overshadowed actual incidents and a few massacres were highly publicized, further reinforcing the pioneers’ fears. This was further complicated by trigger-happy emigrants who shot at Indians for target practice and out of unfounded fear.

Given the extremes which tested the emigrants to the limit of their endurance and fortitude, the evidence of crime among the travelers was low. There were no civil laws, lawmen, or courts of law to protect those who crossed the plains. The military offered some protection near the forts, but that was limited.

As a result, wagon trains carried out their own justice and made their own laws. Before the trains even left Missouri, one of the first tasks was to draw up a constitution regulating conduct and setting laws the party would abide by in the wilderness. Minor crimes generally received only mediation. Serious crimes such as murder, rape, theft of horses were addressed formally. The emigrants would choose a judge, form a jury and hold a trial to the standards they were familiar with. Punishments for these serious offenses included banishment from the wagon train and hanging.

Shootings were common, but what is rarely heard about in trail history is that nearly 200 people were murdered on the Oregon-California Trail in the mid-1800s. Only one man who was murdered on the trail, Ephraim Brown, lies in a grave with a known location. Missouri pioneer Brown, a leading figure on a wagon train bound for California, was killed near South Pass, Wyoming, in 1857 in what appears to have been a bitter family dispute.

Other Deaths:

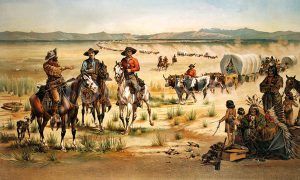

The Donner Party by Andy Thomas

Starvation often threatened emigrants, but it killed the draft animals more often. However, it was the cause of death for the Donner-Reed Party of 1846 when the group was stranded by an early snowfall in the high Sierras. Thirty-five members of the party died, and many of the 47 survivors ate their dead.

“Looked starvation in the face. I have seen men on passing an animal that has starved to death on the plains, stop and cut out a steak, roast and eat it and call it delicious.” — Clark Thompson, 1850

The stress of the journey, sickness, and hardships encountered sometimes led to suicides.

Other deaths were caused by sharp instruments, falling objects, buffalo hunts, and other calamities.

Wagon Train Children

On some occasions, many emigrants, particularly children, straggled behind for too long, wandered off looking for flowers or berries, or attempted to hunt while traveling. Though many made their way back to their camps, some were thought to have fallen prey to wild animals or Indians and left behind.

During these dangerous times, travelers often left warning messages to those journeying behind them if there was an outbreak of disease, bad water, or hostile Indians nearby.

Over time, conditions along the Oregon Trail improved.

Bridges and ferries were built to make water crossings safer. Settlements and other supply posts appeared along the way, which gave weary travelers the chance to stock up on supplies, get their horses shod, trade with Indians, and rest and regroup.

Trail guides wrote guidebooks, so settlers no longer had to bring an escort on their journey. Unfortunately, not all the books were accurate and left some settlers lost and in danger of running out of provisions.

Other Hardships

The dangers and death along the Oregon Trail caused suffering to the pioneers, but additional hardships were also experienced.

The journey west was not for the faint of heart. Difficulties ranged from the relatively minor, such as boredom or the irritation of the dust kicked up by the feet of hundreds of oxen.

The overlanders encountered their first hardship before they even left home, as leaving friends and family behind was difficult, and they would likely never see them again.

“When Grandmother learned the next morning that they were then on their way, she kneeled down and prayed that God would guard and protect them on their perilous journey.”

— Henry Garrison describing his uncle’s parting from Iowa

They also left behind several keepsakes and heirlooms as each family was required to pack all of their supplies and belongings into covered wagons that offered just over 80 square feet of space to travel on the 2000 mile long Oregon Trail. Later, many of their articles, too precious to leave behind in the East, would also be abandoned to spare weary oxen.

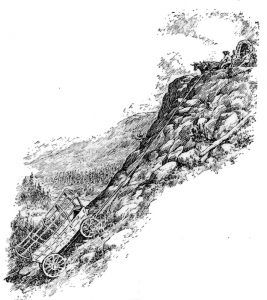

On steep descents, emigrants had to lock the wheels of the wagons and lower them using chains and ropes.

The road beyond Fort Laramie began the climb into the Rocky Mountains, and to keep the animals moving required the wagons to lighten their loads. The road was soon littered with items that had seemed like treasures in Missouri but were now often impossible to keep.

“We passed today the nearly consumed fragments of about a dozen wagons that had been broken up and burned by their owners: and near them was piled up, in one heap, from six to eight hundred weight of bacon, thrown away for want of means to transport it further. Boxes, bonnets, trunks, wagon wheels, whole wagon bodies, cooking utensils, and, in fact, almost every article of household furniture were found.”

– Captain Howard Stansbury, 1852

With their wagons packed full of necessities, nearly everyone, many barefoot, walked along with their herds of cattle and sheep. The tiring pace of the journey, averaging about 15 miles per day, often resulted in exhaustion and general weakness.

Often travelers underestimated the number of supplies to bring, causing them to ration their food. This occurred to the Whitman Party in 1836, who ended up having to live off of dried buffalo meat. Other supply shortages included spare wagon parts and even clothing.

Boredom was often a problem after day after day of walking and eating the same diet. This was especially true during the 427 miles across Nebraska. Many pioneers complained of the unchanging landscape prompting one early pioneer to express that, after spending 30 days crossing Nebraska with hardly a change of scenery, he hoped the Indians would attack to relieve the boredom. After crossing most of Nebraska, pioneers were thrilled when they arrived at the landmarks of Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff.

Go-Backs and Turnarounds

The hardships and homesickness caused about one in ten emigrants to turn back. They were called “go-backs” or “turnarounds.”

Some of these made it only as far as the jumping-off points along the Missouri River, where they found the costs of making the trip prohibitive or were scared off by stories they heard. Others made their way further down the trail before turning around.

Mary Ellen Todd, who left Arkansas for Oregon in 1852, claimed of the 100 wagons that began the trip, 96 of them turned around after traveling a considerable distance.

In 1850, Oregon Trail pioneer Seth Lewelling met a 300 wagon caravan retreating from St. Joseph, Missouri, one of the jumping-off towns. Whether due to poor planning or loss, the wagon train had insufficient provisions to make the entire distance of the trail.

In 1850, there was a draught along the trail, which coupled with high traffic caused several wagons to return.

In 1852, Ezra and Eliza Jane Meeker reported meeting 11 wagons moving slowly east against the traffic flow. That group had made it as far as Fort Laramie, Wyoming, before losing the last of its menfolk. The wagons, driven by women, were returning in hopes of regaining their homes in the east.

These “go-backs” were a significant source of information of the wonders, dangers, and disappointments of what lay upon the trail.

Despite the hardships of the experience, few emigrants ever regretted their decision to move west.

“Those who crossed the plains…never forgot the ungratified thirst, the intense heat and bitter cold, the craving hunger and utter physical exhaustion of the trail…But there was another side. True they had suffered, but the satisfaction of deeds accomplished and difficulties overcome more than compensated and made the overland passage a thing never to be forgotten.”

— An Emigrant Pioneer

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

Crime and Punishment on the Overland Trails

Disease and Death on the Overland Trails

Ephraim Brown – Murdered on the Oregon Trail

Eye Witness Accounts on the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Sager Orphans on the Oregon Trail

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Sources:

National Park Service

Oregon-California Trails Association

Oregon Trail 101

Oregon Trail Center

Wagner, Tricia Martineau; It Happened on the Oregon Trail, TwoDot, 2004