Located in the northwest corner of Claiborne County, Mississippi, Grand Gulf was once a bustling riverport town in the first half of the 19th Century. Between the years of 1680 and 1803, the land that would become Mississippi Territory was controlled by the French and Spanish governments. During that time, land grants were issued to settlers, including several by the Spanish in the late 1700s, in the area where Grand Gulf would later be established. Some of these early grants were made to the White, Marble, and Smith families, who would eventually form a town.

Two of these early settlers were Colonel Thomas Lilly White and his oldest son, Captain Thomas White, Jr., who had served in the Revolutionary War in North Carolina. In 1792, Thomas White, Sr. received one of the Spanish land grants, and the family moved to the Natchez District in present-day Claiborne County.

Other family members, including his son, would also acquire land there. Thomas White, Sr. would later be appointed to serve on the first panel of jurors in Claiborne County in 1802. He also was one of three commissioners appointed to buy land for the first courthouse in nearby Port Gibson. He died in 1804 at an advanced age. Along with other early settlers, the Whites had not only Indians to contend with but also the notorious outlaws who roamed the Natchez Trace. However, they stayed and carved civilization from the wilderness.

Located near the Mississippi River, about eight miles northwest of Port Gibson, the Big Black River flowed into the Mississippi at this point, offering easy access to river trade. As the area began to flourish, three men — Ezra Marble, Turpin White, and Amos Whiting decided to lay out a new town on their property in 1828. William Davis surveyed the land, laying out 80 city blocks. It was named after a large whirlpool formed when the Mississippi River struck a great rock just north of the townsite.

The new village boasted three stores, a post office, a tavern, and several houses by the following year. Soon, a stage line began operating between Grand Gulf and Port Gibson, and numerous steamboats stopped at Grand Gulf’s port. In 1830, a visiting writer documented his impressions of the fledgling community:

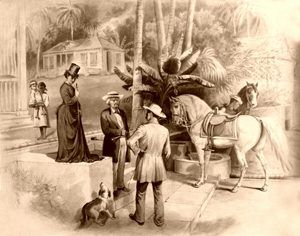

“Towns usually arise from the location of a county seat or a shipping port. In these towns are the banks, the merchants, the post offices, and the several places of resort for business or pleasure that draw the planter and his family from his estate. Each town is a center of a circle that extends many miles around it into the country and daily attracts all within its influence. The ladies come in carriages to shop; the gentlemen, on horseback, to do business with their commission merchants, visit the banks, hear the news, dine together at hotels, and ride back in the evening. Showy carriages and saddle horses are the peculiar characteristics of the moving spectacle in the streets of the southwestern town.”

“The society, like most new towns in the state, is composed of young men, merchants, lawyers, and physicians, most of whom are bachelors. There is something striking to the eye of the northerner on entering one of these southwestern villages. He will find every third building occupied by a lawyer or a doctor, around whose open doors will be congregated knots of young men in deshabille (carelessly dressed), smoking and conversing, sometimes with animation, but more commonly, with an air of indifference. He will pass by stores and see them cluster around him, fashionably dressed, with sword canes dangling from their fingers. Whenever he turns his eyes, he sees nothing but young fellows. He sees few women. If he remains a season, he may attend several public balls in the hotel where he will meet with beautiful females from plantations twenty miles around.”

Although this area was then considered the western frontier, early settlers were generally well-educated and brought a cultured lifestyle from the old south. Many of these early settlements along the Mississippi River were islands of relatively cultured civilization surrounded by primeval swamps and forests and roaming Indians, wolves, bears, and alligators.

Yet, in the middle of this wilderness, the Port Gibson-Grand Gulf area offered the finest in amenities to the traveler. When Captain Edmund Winston of Fredericksburg, Virginia, stayed a week at the Planter’s Hotel in Port Gibson, he wrote a letter to his sister on November 3, 1828, stating:

“The town has improved wonderfully in the last few years, and the slave trade is on the ‘boom’ here. The courthouse is not a giant office building of justice yet, but it is clean, and the officials are the wisest and most polished kind. “I resided at the Tavern my entire time, though I was invited by many to partake of their hospitality and invited so sincerely. The menu at the Tavern is something rare. I am sending it. The steward, named McMakin, comes to the parlor door at the dining hour with carving knife and fork crossed before his broad breast, face glowing with smiles, clad in a snowy stiffly starched apron, and says, “Good evening, ladies fair, Generals and Captains; walk in and partake of barbecued venison, pork, beef, roast turkey, stuffed duck, geese, fish from the biggest river on earth; chicken salad, shrimp and crabs killed in duels for the approval of beautiful ladies appetites, cake and jellies for the married, cold potato custard for those in love, gin from Holland; wines from France and Spain. Come one and all. Eat and drink all that you can contain.” I felt, as I saw the merriment this speech created, and as I enjoyed the feast, that I was in the Land of Promise. Your brother, E.W.”

In 1833, Grand Gulf was incorporated. During these early years, cotton was king in the rich bottomlands with easy access to the Mississippi River. Many made Fortunes through the availability of cheap land and prudent management of slave labor. In less than nine months between September 1834 and May 1835, 37,770 bales of cotton were shipped from Grand Gulf. The town continued to grow, surpassing the Claiborne County Seat of Port Gibson’s population and became the third-largest town in Mississippi.

As the center of the cotton shipping business, it soon boasted a large hospital, numerous retail stores, a theater, and about 1,000 people by the late 1830s. Over twenty steamboats would stop in this Mississippi town to trade and restock in a typical week. These boats carried goods and new arrivals, such as young Jewish merchants. During this time, several Jewish peddlers settled in the flourishing town, many of whom wished to escape from the larger port of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Though larger and wealthier than nearby Port Gibson, Grand Gulf’s heydays wouldn’t last. It would soon be devastated by a series of disasters beginning in 1843 with a terrible yellow fever epidemic. The disease was so rampant in the area that it prompted Northern newspapers to report on the events. On September 22, 1853, the Pittsfield, Massachusetts newspaper stated:

“At New Orleans… 241 deaths this week from yellow fever… The New Orleans Picayune says yellow fever at that place continues very malignant; the blacks, however, are the principal victims… At Grand Gulf, the fever is raging with great severity; half the residents were taken down in one week. There was only one physician in the place, and he completely was worn out with his arduous duties. At Port Gibson, the fever was more malignant than even at New Orleans… Several plantations along the Mississippi were suffering dreadfully from fever.”

About nine years later, a steamboat explosion would decimate Grand Gulf’s docking facilities. On January 14, 1852, the steamboat George Washington went from Cincinnati, Ohio, to New Orleans, Louisiana. At about 1:00 p.m., as she neared Grand Gulf, her boilers exploded, burning the ship and landing facilities at the water’s edge. She had in tow two heavily laden barges, both of which were totally consumed. But these losses are insignificant when compared with the destruction of human life. Killed were the ship’s cook, a fireman, six deckhands, and six deck passengers at the moment of the explosion. Several more passengers were badly burned, two of which later died from their injuries.

The very next year, 1853, a tornado devastated much of the town. That same year, the Mississippi River began to change its course, and its current began to whittle away at the town. By 1860, the river had eroded some 52 blocks of the townsite, which had been reduced to just 158 people. By the time the Civil War began, only a few abandoned buildings were left.

First Battle of Grand Gulf – In May 1862, cannoneers of the Confederate Brookhaven Light Artillery, commanded by Captain James Hoskins, reached Grand Gulf. Hoskins had gunners in place and four 6-pounders on the bluffs behind the village. The task was to harass the Federal fleet commanded by Flag Officer Commodore David Farragut. On May 26, 1862, the Confederate artillerists wisely let three Union warships pass undisturbed, but as unarmed transports drew abreast, the four 6-pounders roared into action, scoring hits on the Laurel Hill. Before the warships could get into a position to return the fire, the Rebel troops were gone. Captain Thomas Craven, commander of the warship Brooklyn, determined to teach the Confederates a lesson by bombarding the town of Grand Gulf. Intending to burn the town, Captain Craven conferred with Brigadier General Thomas Williams and agreed to spare the town and send Federal forces to levy a forced contribution of livestock and wood upon the populace. Under cover of darkness on the night of June 8, 1862, the Confederates once again moved 6 and 12-pounders into position on the ridge behind Grand Gulf. The next morning, these guns’ crews struck the Wissahickon and Itasca while these vessels were passing the batteries.

Battle of Grand Gulf – In 1863, Union General Ulysses S. Grant began his campaign against Vicksburg. On April 29, 1863, he aimed to force a crossing of the Mississippi River from Louisiana at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, and then move on to Vicksburg from the south.

In the first battle of Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign, Union Rear Admiral David D. Porter and Confederate General John S. Bowen were the leaders. The skirmishing began when Admiral Porter led seven ironclads in an attack on the fortifications and batteries at Grand Gulf to silence the Confederate guns and then secured the area with troops of Union General John A. McClernand’s XIII Army Corps, who were on the accompanying transports and barges.

A Union fleet of seven ironclads bombarded the Grand Gulf defenses for five hours to silence the Confederate guns and prepare the way for a landing.

The attack by the seven ironclads began at 8:00 a.m. and continued until about 1:30 p.m. During the fight, the ironclads moved within 100 yards of the Rebel guns and silenced the lower batteries of Fort Wade; however, the Confederate upper batteries at Fort Cobun remained out of reach and continued to fire.

Ultimately, the Union fleet sustained heavy damage and failed to achieve its objective, resulting in Union Rear Admiral David D. Porter declaring: “Grand Gulf is the strongest place on the Mississippi.” The Union ironclads and transports were forced to draw off. After dark, however, the ironclads engaged the Rebel guns again while the steamboats and barges ran the gauntlet.

Though the Grand Gulf assault was disappointing, it did not end Grant’s ambitions to cross the river, and he began to move his troops south. While Admiral Porter provided cover for the transport vessels’ movement, Grant was busy with intelligence-gathering operations.

Grant’s men marched across Coffee Point to below Grand Gulf. After the transports had passed, they embarked the troops at Disharoon’s plantation and disembarked them on the Mississippi shore at Bruinsburg, below Grand Gulf. The men immediately began marching overland towards Port Gibson.

Though the battle resulted in a Confederate victory, the loss at Grand Gulf caused just a slight change in Grant’s offensive. The estimated Union casualties were 80; the Confederate number is unknown.

The few Grand Gulf buildings left standing before the assault were destroyed, and Grand Gulf was never rebuilt after the war. Today, a few trailer homes stand near what was Fort Cobun and an abandoned and tumbling-down church, which will soon be gone. However, the town and the battle are commemorated at the Grand Gulf Military Park.

Grand Gulf Military Park

Standing on land that once possessed one of the most prosperous ports along the Mississippi River, the Grand Gulf Military Park was officially opened in 1962.

Dedicated to preserving the memory of the town and the Battle of Grand Gulf, the park features a museum, several historic buildings dating to Grand Gulf’s heydays, a cemetery, and the Civil War sites of Fort Cobun and Fort Wade.

A tour through the 400-acre park, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, provides visitors a peek at the past through displays in the museum, buildings, equipment on the grounds, and numerous historical markers.

Visitors can tour the park by either driving or walking. The best place to start is in the museum, which provides information on the tour and features historical items, artifacts, and photographs from the old town of Grand Gulf and the Civil War.

Sitting atop the hill above the Civil War batteries of Fort Wade, one of the oldest homes in the area and one of only two original buildings left of the old town of Grand Gulf, is the Spanish House. This house was built in the late 1790s of cypress, poplar, and heart pine and wooden pegs instead of nails. The Spanish-built structure represents several homesteads built in the area when it first settled. Its proximity to Fort Wade during the Battle of Grand Gulf caused considerable damage from Federal shells in 1863. It was repaired after the war and continued to be used. In 1958, it was restored to its original condition.

Down the hill from the Spanish House is the site of Fort Wade, an earthwork fortification constructed by Confederate troops during the early days of the Vicksburg Campaign. It was designed to defend the Grand Gulf area and attack any Union ships or troops attempting to move up or down the Mississippi River. Situated on a shelf overlooking the charred ruins of Grand Gulf, Captain Henry Guibor’s and Colonel William Wade’s Missouri Batteries manned its four big guns.

The Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church at the Grand Gulf Military Park was moved

from nearby Rodney, Mississippi, by Kathy Alexander.

On April 29, 1863, five of Union Admiral David D. Porter’s ironclads came downriver and took a position about a quarter of a mile from Fort Wade. A terrible artillery duel ensued within no time, and Fort Wade was smothered by the storm of shots and shells delivered by the five gunboats. Two 32-pounder rifles were dismounted, and the parapet was knocked to pieces. Colonel William Wade was killed, and by 11:00 a.m., Fort Wade had been silenced, and Porter’s entire squadron concentrated its fire on Fort Cobun.

One of the most beautiful buildings in the park is not native to Grand Gulf; but instead came from the nearby settlement of Rodney, now a ghost town. The Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church was built in 1868 when Rodney was a thriving riverport town. However, when the Mississippi River altered its course, Rodney began to die and, by 1933, was called home to less than 100 people. In February 1969, the Natchez-Jackson Diocese deeded the property to the Rodney Foundation for the most outstanding of the few remaining examples of carpenter gothic church architecture in Mississippi. Later, the building was donated to the State of Mississippi and moved to Grand Gulf Military Park in 1983. Today, religious and other groups use the restored building as a non-denominational chapel.

The park also features another period home: a carriage house, a jail, the site of Fort Cobun, a water mill, and more.

In addition to the historical sites and buildings, Grand Gulf Military Park also features a campground, which accommodates both tents and RV’s, picnic areas, a pavilion for large group events, hiking trails, and an observation tower. The park is eight miles northwest of Port Gibson, Mississippi, off Highway 61. A small admission charge ($3/person in February 2013) to tour the park. It is one of the best values Legends’ found during our month-long tour of the Magnolia State.

More Information:

Grand Gulf Military Park

12006 Grand Gulf Road

Port Gibson, Mississippi 39150

601-437-5911

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Natchez Trace – Traveled For Thousands of Years

Rodney, Mississippi – From Prominence to Ghost Town

The Vicksburg Campaign — Vicksburg is Key!

See Sources.