Massacre of Marais des Cygnes, Kansas

As early as 1856, trouble arose between the free-state and pro-slavery settlers in Linn County, Kansas, when a large body of southerners marched through the area, destroying what little property there was and capturing the free-state settlers who were not fortunate enough to get out of the way.

One of the men who escaped, although vigorously pursued, was James Montgomery, who became the acknowledged leader of the free-state men in the county. Various outrages continued until 1857 when General James H. Lane assembled a company to intimidate the pro-slavery men of Linn County and the adjoining counties of Missouri.

He established headquarters at Mound City and, for a time, quelled the forays. However, after his force was disbanded, trouble broke out afresh. Then, James Montgomery took the field in defense of the frightened free-state settlers and ordered the pronounced leaders of the pro-slavery party out of the county. Many of them obeyed the summons and moved with their families to Missouri.

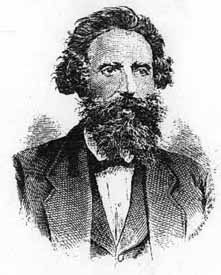

Colonel James Montgomery

Around Trading Post, Kansas, located on the Marais des Cygnes River, a bitter pro-slavery settlement had grown up, the leader of which was Charles A. Hamilton. The post became the rendezvous of the abolition haters for the immediate vicinity and the territory across the line. Montgomery was determined to break up this gang. He began by emptying the contents of several barrels of whiskey on hand at the “doggery,” and leaving a notice for the ruffians to quit Kansas Territory. Hamilton and some of his neighbors left the territory. Subsequently, they called a meeting at Papinsville, Missouri, to incite the men to invade Kansas. Hamilton addressed the meeting, and with a unanimous vote, it was decided to invade the territory and exterminate the free-state settlers in Linn County.

When the party arrived at the line between Missouri and Kansas, a halt was ordered to make final arrangements. One of the men named Barlow, who had spoken against the invasion at the meeting, again did so, this time with better effect. They were on the border of the hated but dreaded Kansas, and Barlow assured them that the crack of the Sharpe’s rifles might be expected from Montgomery’s men at any minute. A panic seemed imminent, but at the summons of Hamilton, about 30 of the most resolute rode after their leader and reached Trading Post on the morning of May 19, 1858, where they captured 11 free-state men, nearly all of whom were known to Hamilton or some member of his party. They were not known to have taken an active part in the disputes, and having been neighbors of Hamilton, they had no suspicion that he meant to harm them, especially as they were guilty of no offense but that of being free-state men.

The 11 victims were driven rapidly into a deep ravine, lined up facing east. Hamilton then ordered his men to form in front of them and fire. One of the men turned out of the line and refused to do so, but Hamilton brought the remainder into line and fired the first shot himself. Five men were seriously injured, one escaped unharmed, and the rest were murdered.

After finding the victims, the community quickly came together and tried to render aid. As word spread, Montgomery’s Jayhawkers pursued Hamilton to no avail. A few weeks after the massacre, John Brown arrived and built a two-story log “fort,” about 14 x 18 feet, which he occupied with a few men through the summer. In December, he raided Missouri, where 11 slaves were liberated, and one man was killed.

The land was later sold to Brown’s friend Charles C. Hadsall, who agreed to let Brown occupy it for military purposes. Brown and his men withdrew at the end of the summer, leaving the fort to Hadsall, who later built a stone house adjoining the site of Brown’s fort.

Although a reward was offered for Hamilton’s capture, he managed to avoid it. After the Kansas-Missouri Border War, he returned to his home in Georgia, where he was quickly stripped of everything by his creditors due to heavy debt, then he wound up in Texas. In 1861, he moved back east, raised a Virginia regiment under Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and served as a Colonel. After the Civil War, he returned to Georgia, where he died some years later.

News of the Massacre horrified the U.S., with John Greenleaf Whittier, a famous poet, penning the poem “Le Marais du Cygne,” which appeared in the September 1858 Atlantic Monthly publication.

A BLUSH as of roses

Where rose never grew!

Great drops on the bunch grass,

But not of the dew!

A taint in the sweet air

For wild bees to shun!

A stain that shall never

Bleach out in the sun!

Back, steed of the prairies!

Sweet songbird, fly back!

Wheel hither, bald vulture!

Gray wolf, call thy pack!

The foul human vultures

Have feasted and fled;

The wolves of the Border

Have crept from the dead.

From the hearths of their cabins,

The fields of their corn,

Unwarned and unweaponed,

The victims were torn,

The whirlwind of murder

Swooped up and swept on

To the low, reedy fen-lands,

The Marsh of the Swan.

With a vain plea for mercy

No stout knee was crooked;

In the mouths of the rifles

Right manly they looked.

How paled the May sunshine,

O Marais du Cygne!

On death for the strong life,

On red grass for green!

In the homes of their rearing,

Yet warm with their lives,

Ye wait the dead only,

Poor children and wives!

Put out the red forge fire,

The smith shall not come;

Unyoke the brown oxen,

The ploughman lies dumb’.

Wind slow from the Swan’s Marsh,

O dreary death train,

With pressed lips as bloodless

As lips of the slain!

Kiss down the young eyelids,

Smooth down the gray hairs;

Let tears quench the curses

That burn through your prayers.

Strong men of the prairies,

Mourn hitter and wild!

Wail, desolate woman!

Weep, fatherless child!

But the grain of God springs up

From ashes beneath,

And the crown of his harvest

Is life out of death.

Not in vain on the dial

The shade moves along,

To point the great contrasts

Of right and of wrong:

Free homes and free altars,

Free prairie and flood,

The reeds of the Swan’s Marsh,

Whose bloom is of blood!

On the lintels of Kansas

That blood shall not dry

Henceforth the Bad Angel

Shall harmless go by;

Henceforth to the sunset,

Unchecked on her way,

Shall Liberty follow

The march of the day.

Marais des Cygne Massacre Monument

The State of Kansas later appropriated $1,000 for a memorial monument erected at Trading Post, beneath which rested the ashes of four of the victims.

Today, the massacre site continues to display Hadsall’s stone house, which contains a museum on the upper floor operated by the Kansas Historical Society.

The site is located five and one-half miles northeast of Trading Post, Kansas, on U.S. Highway 69.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2023.

Also See:

Soldiers & Officers in American History

About the Article: Most of the above text is based on information in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.