By Wilbur F. Gordy in 1903

Daniel Boone was a pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States.

In the mid-1700s, the English colonists lived almost entirely between the Allegheny Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean. These narrow boundaries continued until the beginning of the American Revolution. However, by the end of the war, the western boundary extended to the Mississippi River, and several pioneers and backwoodsmen began to move westward.

One of the most noted of these pioneers was Daniel Boone. He was born in Berks County, Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1734, the sixth of 11 children in a family of Quakers. Caring little for books as a child, he spent most of his time hunting and fishing. He loved the woods and soon became an expert rifleman. An early story tells of when he was just a young boy; he wandered one day into the forest some distance from home, where he built himself a rough shelter of logs. There, he would spend days at a time with only his rifle and game for company. This free wildlife trained him for his future career as a fearless hunter and woodsman.

When Daniel was about 13, he moved with his family to North Carolina and settled on the Yadkin River. As a young man, he served with the British military during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), a struggle to control the land beyond the Appalachian Mountains. In 1755, he worked as a wagon driver in General Edward Braddock’s attempt to drive the French out of the Ohio Country, which ended the Braddock expedition at what is known as the Battle of the Monongahela.

Boone returned home after the defeat and married Rebecca Bryan, a neighbor in the Yadkin Valley, on August 14, 1756. The couple initially lived in a cabin on his father’s farm before building a small cabin in the wilderness, far removed from other settlers’ homes. The couple would eventually have ten children.

In 1759, a conflict erupted between European colonists and the Cherokee Indians, their former allies, in the French and Indian War. After the Cherokee raided the Yadkin Valley, many families, including the Boones, fled to Culpepper County, Virginia. Boone served in the North Carolina militia during this “Cherokee Uprising.” His hunting expeditions deep into Cherokee territory beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains separated him from his wife for about two years.

During this time, Boone began exploring the territory to the west, pushing his way as far as Boone’s Creek, a branch of the Watauga River in Eastern Tennessee. Near this creek, there yet stands a beech tree with the inscription: “D. Boon Cilled a Bar [killed a bear] on [this] tree in the year 1760.”

On May 1, 1869, Boone and five other men started crossing the Alleghany Mountains. For five weeks, the bold travelers picked their way through the pathless woods. In June, they reached Kentucky; they were rewarded for all their hardships. Here was a beautiful country with abundant game, including deer, bears, and herds of bison. They decided to stay for a while and promptly put up a log shelter.

Six months after their arrival, Boone and a man named Stewart had an unpleasant experience. While off on a hunting expedition, they were captured by an Indian party. For seven days, the warriors carefully guarded their prisoners. But, on the seventh night, having gorged themselves with game killed during the day, the Indians fell into a sound sleep. While pretending to be asleep, Boone had been watching this opportunity, quietly awoke Stewart, and the two crept stealthily away. Returning to their camp, they found it deserted. What had become of their friends, they never learned.

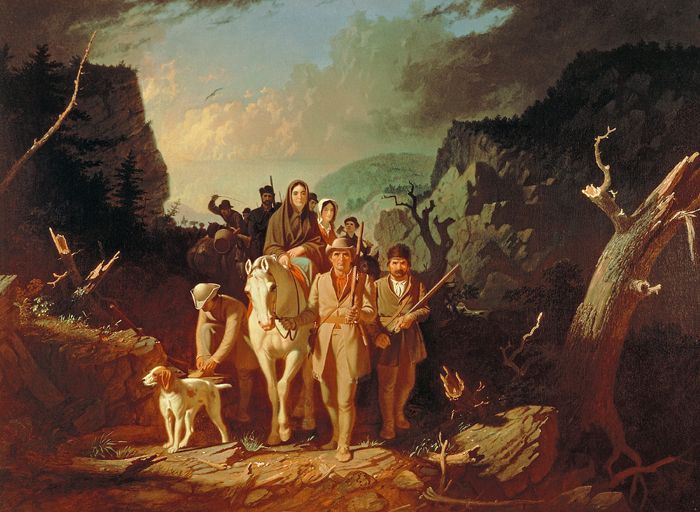

Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap by George Bingham.

Some weeks later, Boone was pleasantly surprised by the appearance at the camp of his brother, Squire Boone, and a companion. The four men lived together without incident until one day, Stewart was surprised and shot by some Indians. Stewart’s death terrified the man who had accompanied Squire Boone so that he gave up the wilderness life and returned to his home.

Boone and his brother remained together in the forest for three months longer, but with their ammunition getting low, Squire returned to North Carolina in May for fresh supplies and horses. Daniel was thus left alone, 500 miles from home. His life was in constant peril from wild beasts and Indians. He dared not sleep in his camp but resorted at night to a canebrake or some other hiding place, where he lay concealed, not even kindling a fire lest its light might betray him. During these months of solitary waiting for his brother, Boone endured many privations. He had neither salt, sugar, nor flour, his sole food being game brought down by his rifle. But his brother returned in July, bringing provisions.

After two years of this experience in the wilderness, Daniel Boone returned to his home on the Yadkin River to prepare to move. By September 1773, he had sold his farm and was ready to go with his family to settle in Kentucky.

His enthusiastic reports of the fertile country found eager listeners. When his party was ready to go, it not only included his own family but also five more families and 40 men, with a sufficient number of horses and cattle. Unfortunately, they were attacked on their way by Indians, and six men, one of Boone’s eldest sons, James, were killed. Discouraged by this setback, the party returned to the nearest settlement, and the migration westward was postponed.

But Boone’s unflinching purpose was to settle in the beautiful Kentucky region. It had already become historic, for the Indians called it a “dark ground,” a “bloody ground,” and an old Indian Chief had related to Boone how many tribes had hunted and fought on its disputed territory. None of the Indians held an undisputed claim to the land.

Nevertheless, a friend of Boone’s, Richard Henderson, and other white men made treaties with the powerful Cherokee, who allowed them to settle there. As soon as it became certain that the Cherokee would not interfere, Henderson sent Boone, in charge of 30 men, to open a pathway from the Holston River over Cumberland Gap to the Kentucky River. This is still known as the Wilderness Road, along which thousands of settlers made their way afterward.

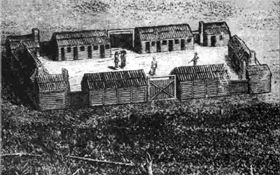

Fort Boonesborough

On reaching the Kentucky River, Boone and his men built a fort on the left bank of the stream, which they called Boonesborough. Its four stout walls comprised the outer sides of log cabins and a 12-foot-high stockade. There were loopholes in all the cabins and a loopholed blockhouse at each corner of the fort.

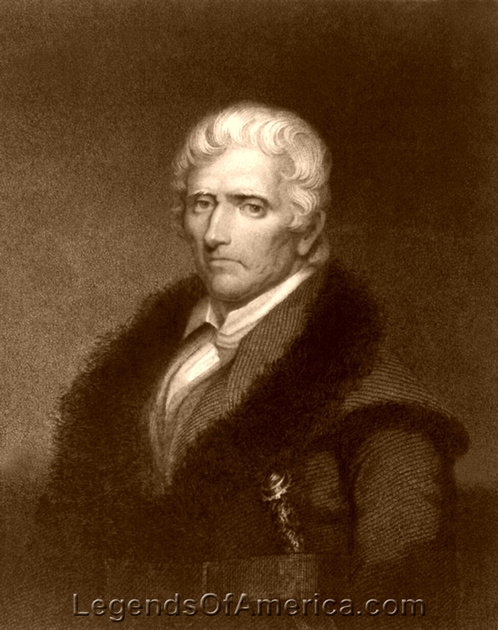

Daniel Boone, the leader of this settlement, had an engaging personality. He was a tall, slender backwoodsman with muscles of iron and a rugged nature that enabled him to endure great hardship. Quiet and serious, he possessed a courage that never shrank in the face of danger. Men had confidence in him because he had confidence in himself. Moreover, his kind heart and tender sympathies won lasting friendships. He usually, though not always, dressed as an Indian. A fur cap, a fringed hunting shirt, leggings, and moccasins, all made of wild animals’ skins, made up his ordinary costume.

His log cabin, out in the clearing not far from the fort, was a simple home with rude furnishings. A ladder against the wall was the stairway by which the children reached the loft. Pegs driven into the wall held the scanty family wardrobe, and the family meal was spread upon a rough board, supported by four wooden legs.

Daniel Boone at his cabin.

Plain and simple food was abundant. Bear’s meat was a substitute for pork, and venison for beef. As salt was scarce, the beef was not salted down or pickled but was jerked by drying in the sun or smoking over the fire. Corn was also an essential article of diet. When away from home to hunt game or follow the war trail, sometimes the only food the settler had was the parched corn he carried in his pocket or wallet. Every cabin had its hand-mill for grinding the corn into meal and a mortar for beating it into hominy. The mortar was made by burning a hole into the top of a block of wood.

A pioneer boy found his life a busy and interesting one. While still young, he received careful training in imitating the notes and calls of birds and wild animals. He learned how to set traps and shoot a rifle with an unerring aim. At 12 years of age, he became a fort soldier, with a porthole assigned to him for use in case of an Indian attack. He also received careful training in following an Indian trail and concealing his own when on the warpath. For expert knowledge of this kind was necessary amid dangers from unseen foes that were likely to creep stealthily upon the settlers at all times, whether they were working in the clearings or hunting in the forest.

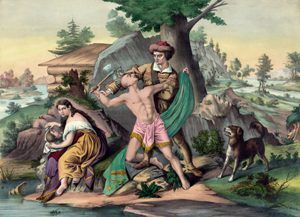

After building the fort, Boone returned to his home in North Carolina for his family. Some months after the family reached Boonesborough, Boone’s daughter, with two girlfriends, was floating in a boat one day near the riverbank. Suddenly, five Indians darted out of the woods and, seizing the three girls, hurried away with them. When in their flight, the Indians observed the eldest of the girls breaking twigs and dropping them in their trail, they threatened to tomahawk her unless she stopped it. But watching her chance, she, from time to time, tore off strips of her dress and dropped them as guides to the pursuing whites.

As soon as possible after hearing of the capture, Boone, with seven other men from the fort, started upon the trail of the Indians and kept up the pursuit until, early on the second morning, they discovered the Indians sitting around a fire cooking breakfast. Suddenly, the whites, firing a volley, killed two Indians and frightened the others so severely that they beat a hasty retreat, leaving the girls uninjured.

Early in 1778, Boone and 29 other men were captured and carried off by a party of Indian warriors. At that time, the Indians in that part of the country were fighting on the English side in the Revolution, and as they received a ransom for any Americans they might hand over to the English, they took Boone and the other men of his party to Detroit.

Although the English offered $500 for Boone’s ransom, the Indians refused to let him go. They admired him so much that they took him to their home and adopted him into their tribe with due ceremony. Having plucked out all his hair except a tuft on the top of his head, they dressed this in feathers and ribbons as a scalp lock. Next, they threw him into the river and gave his body a thorough scrubbing to wash out all the white blood. Then, daubing his face with paint in true Indian fashion, they looked upon him with immense satisfaction as one of themselves.

Boone remained with them for several months, during which he made the best of the life he had to lead. But when he heard that the Indians were planning an attack upon Boonesborough, he determined to escape if possible and give his friends a warning. His own words tell the story: “On June 16, before sunrise, I departed most secretly, and arrived at Boonesborough on the 20th after a journey of 160 miles, during which I had but one meal.” He could not get any food because he dared not use his gun, nor would he build a fire for fear of discovery by his foes. He reached the fort safely, where he was of great service in beating off the attacking party.

But this is only one of the many hairbreadth escapes of the fearless backwoodsman. Once, while in a shed looking after some tobacco, four Indians with loaded guns appeared at the door. They said, “Now, Boone, we got you. You no longer get away. You no cheat us anymore.” In the meantime, Boone had gathered up in his arms several dry tobacco leaves, and the dust of these suddenly filled the Indians’ eyes and nostrils. Then, while they were coughing, sneezing, and rubbing their eyes, he made good his escape.

But from all his dangerous adventures, Boone came out safely and, for years, remained the leader of the settlement at Boonesborough. He was undoubtedly a masterful leader in that early pioneer life in Kentucky. The solitude of the wilderness never lost its charm for him, even to the last of his long life. He died in 1820 at the age of 85. It has been said that, but for him, the settlement in Kentucky could not have been made for many years.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2025.

Source – Gordy, Wilbur F.; American Leaders and Heroes; Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1907.

Also See:

The Wilderness Road Opens Kentucky