“A gambler is one who teaches and illustrates the folly of avarice; he is a non-ordained preacher on the vagaries of fortune and how to make doubt a certainty. He is one who, in his amusements, eliminates the element of chance; chance is merely the minister in his workshop of luck; money has no value except to back a good hand.” — Jefferson R. Smith

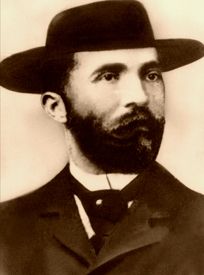

One of the most well-known con men of the 1800s, Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith, II, operated several “rackets” in the American West for decades. From Texas to Colorado, to Alaska, Smith organized groups of bunko men into gangs that operated shell games, crooked gambling, and other scams with the likes of such men as Texas Jack Vermillion, “Big Ed” Burns, and numerous others.

Born November 2, 1860, in Newnan, Georgia, Smith belonged to a well-educated, wealthy family. His great-grandfather owned one of the finest plantations in the area, and his father was a lawyer. But, like many southern families, their prosperity came to an end after the Civil War.

In 1876, the family moved to Round Rock, Texas, where an 18-year-old Soapy would witness the killing of outlaw Sam Bass two years later. Sometime later, Smith moved on to Fort Worth, where he began his career as a bunko artist. He soon formed a small, close-knit group of rogues and thieves to perpetuate his scams, becoming the “King of the Frontier Con Men” as the gang moved from town to town. Unsuspecting citizens practiced their games of choice, which included the shell game, three-card monte, and other “short cons” that could be completed quickly.

By the late 1870’s Smith came up with his ingenious “Prize Package Soap Sell” swindle, whereby he could make money from a large crowd. It was from this scam that he earned the nickname “Soapy.” The con began with Smith setting up a Keiser (a suitcase on a tripod stand) on a busy street corner. In the suitcase would be piles of ordinary soap wrapped in plain paper. As curious passers-by stopped to look, he would begin to wrap some of the soap bars with paper money, ranging from one dollar up to a hundred. Rewrapping in the plain paper, he would mix them with the others and sell the soap for $1-5 per bar. In the “crowd,” Soapy would always have a “shill,” quick to buy a bar of soap, happily opening it to find a $100 bill. The crowd was then anxious to buy their own, which, of course, held nothing but a 5¢ cake of soap. For the next two decades, Smith continued the swindle with great success.

By 1879, Soapy and his gang had moved to Denver, Colorado, where he expanded his operations from not only “short-cons” but also into large scams, including fake stock exchanges and lottery offices. But, he and his men continued their smaller games, as Denver had a wide-open policy towards gambling, making for the perfect setting for their deceitful games. As the money continued to roll in for Soapy, he began to organize many of the men operating in Denver into such a stronghold that he proclaimed himself the boss of Denver’s underworld crime empire.

To continue to operate his many scams successfully, Smith provided kickbacks to saloon owners, had city officials on his payroll, and generally didn’t make the locals his target dupes instead of focusing on travelers just passing through. He also built loyalty in his gang members by being quick to help anyone in need and securing their quick release should they be jailed. Continuing this “philanthropist” attitude, he also made charitable contributions to the churches and the poor of the city. He made his saloons available to ministers for Sunday services, further “endearing” him to the locals.

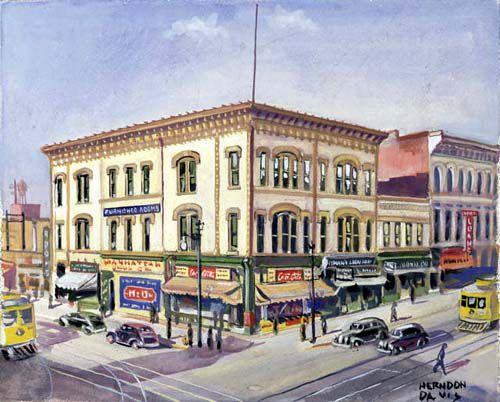

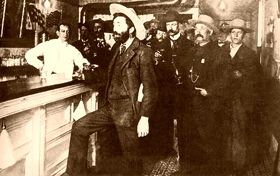

Much of Soapy’s Denver “action” took place in his popular Tivoli Saloon and Gambling Hall, where over the door a sign read: “Caveat Emptor,” which means “Let the Buyer Beware” in Latin. But for those that came through the doors for a much-needed drink of whiskey or in hopes of making their fortune at the gaming tables, they couldn’t read Latin. Interestingly, the famed Bat Masterson worked as a dealer at the Tivoli for a time.

During this time, Soapy was joined by his younger brother, Bascomb, who operated a cigar store, which was a front for crooked card games and other swindles. The gang was also running a fake stock exchange, lottery shops, and bogus diamond auctions.

For several years, Smith settled down, making Denver his home. Though Denver newspapers published that he was in complete control of the criminal and gambling underworld in their city and rightly accused him of being in cahoots with city politicians, including the police chief, his operations continued to prosper.

Though his primary operations were in Denver, Soapy also expanded, and in 1885, he was working with another con artist in Leadville, Colorado. Partnering with a con who went only by the name of Old Man Taylor, the two operated a successful shell game upon the many unsuspecting miners.

In 1891, Soapy talked his otherwise law-abiding brother-in-law from Texas into joining his criminal empire in Denver. William “Cap” Light, who served as a deputy marshal in Belton, Texas, changed his colors when he joined Smith. Light was with Soapy when the gang “attacked” the Glasson Detective Agency. Allegedly the agency had attempted to force a confession from a pretty young girl, and upon hearing about it, Smith and his men raided their offices with pistols in hand. This further led to Soapy’s reputation as a hero with many of the locals.

However, by 1892, polite society in Denver had begun to demand anti-gambling and saloon reforms. Smith had also begun to lose his “crown” as the Denver boss, partly because of rival gangs such as the Blonger Brothers, but also due to his bad temper and drinking problems. He had also become so well-known that it was becoming difficult for his “paid” politicians to continue to turn a blind eye as they had done for so many years.

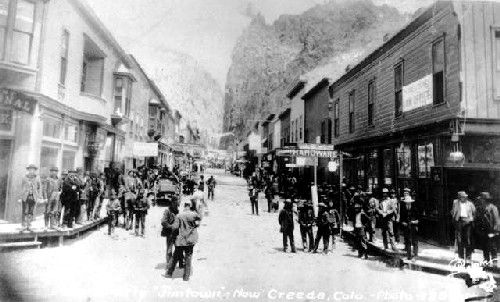

Creede, Colorado 1892

Finding many of his operations restricted and seeing opportunity in the booming mining camp of Creede, Colorado, Soapy and his gang moved their empire. He soon opened the Orleans Club gambling hall and saloon, which operated much like his Tivoli Club in Denver, but without the restrictions imposed in the larger city.

At his new club, Soapy briefly displayed a petrified man for a price of 10¢. The “petrified man,” affectionately called “McGinty,” was also a hoax, as it was nothing more than cement over skeletal remains. However, the oddity brought customers into the saloon and made a small profit. But the objective was that once they were inside, the “dupes” would take advantage of the crooked card games. In the meantime, he had convinced his brother-in-law, William “Cap” Light, to accept a position as a deputy marshal in the camp. Once he had wielded his influence, he claimed himself as the “camp boss.” As such, he protected his friends and associates and expelled violent troublemakers. Again, he also endeared himself to the camp by using his money to build churches and help the poor.

But, Creede’s boomtown days would not last, and Smith soon returned to Denver. The gambling reforms had relaxed once again in the city, and Soapy took up operations at the Tivoli, which had never closed.

Denver City Hall War

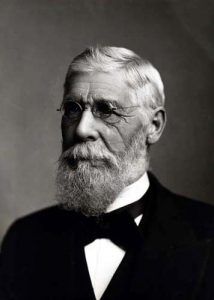

Though organized crime continued rampant in Denver, a new state governor had been elected. Running on a platform of social reform, Davis H. “Bloody Bridles” Waite took office in January 1893 and immediately began to look into corruption in Colorado.

By the following year, in March, he was ready to take on Denver’s politically corrupt machine. He began by firing three members of the fire and police board who he felt were the main instigators of corruption within city hall. He further demanded that the city immediately clean itself up, or he would do it for them.

Replacing the corrupt men with his appointees, the current commissioners refused to leave when the new men arrived. Interestingly, the state charter allowed the governor to make appointments but did not grant him the power to force a municipal government to accept the appointments.

The other corrupt city officials, fearing their positions, backed their bosses and collectively refused to abandon their power. The city also took the matter to the district court, which issued a temporary injunction forbidding the governor from interfering with the city’s appointees. However, Governor Waite and his attorneys insisted that the State’s chief executive was not subject to review by a district court. Continuing to demand that the commissioners step down, Waite threatened to call out the state militia to force them out if need be.

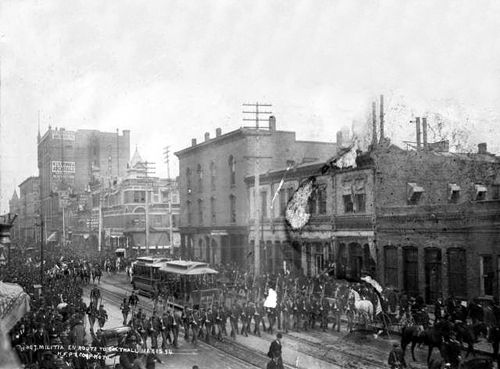

Denver’s mayor then began to recruit a “special police force” to defend city hall against any militia that the governor might send in. The political force, backed by the money and support of organized crime, including Soapy Smith and Lou Blonger, was soon stacked with some 200 unsavory “deputies,” led by none other than Soapy Smith, who was now dubbed “Colonel Smith.”

As armed characters guarded city hall, Governor Waite ordered Colorado State Militia to remove the commissioners forcibly. By mid-March, the governor had declared martial law, and Denver was an armed camp. Waite’s military force of about 200 men marched downtown, along with two Gatling guns and two twelve-pound canons. Pointing their large weapons directly at city hall, they faced the “special police force,” assembled with rifles and shotguns. With “Colonel Smith” at the helm, the “police force” dared the militia to fire on them, threatening to use dynamite if they attacked.

The two sides faced off at a standstill as thousands of civilians looked on. In the meantime, the Chamber of Commerce and other citizens’ committees were working feverishly at a compromise that would prevent the opening of hostilities. Finally, it was agreed that the issue would be left up to the State Supreme Court. Waite withdrew his military forces to await the decision as the city of Denver breathed a sigh of relief.

On April 16, 1894, the Supreme Court decided a conclusive victory for Governor Davis Waite, and the board of commissioners was replaced the next day. The political machine was smashed, and new policies began to be developed almost immediately to clean up the town. Soon, gambling was made illegal in Denver, and the new authorities cracked down hard on other illicit activities, such as prostitution, bootlegging, and many varied bunko activities. One of their priorities was to run Soapy Smith out of town. But Smith took his operations “underground. However, he and his brother, Bascomb, were soon charged with the attempted murder of a saloon manager. Bascomb was arrested and jailed, but Soapy managed to escape, and, a wanted man in Colorado, he soon wandered westward. The Blonger Brothers then took control of the Denver underworld.

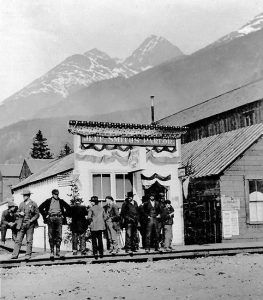

When the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1897, Soapy saw all sorts of new opportunities and soon made his new home in Skagway, Alaska. Like other mining camps, it didn’t take him long to claim himself as “boss” of the town, which he ran with an iron hand. Working from his saloon named Jeff Smith’s Parlor, Soapy’s cons began once again in earnest. His saloon soon became known as the “real city hall,” even though Skagway had an official one. But, some of the Skagway citizens were not so impressed with Soapy, whose heavy drinking and black temper had begun to get entirely out of hand.

Soon, several Skagway citizens had had enough of the man, and a vigilante group, who called themselves the “Committee of 101,” threatened to drive Smith and his gang out of town. However, Soapy retaliated by forming his own group that he said had more than 300 members. Hoping to force the vigilantes into submission, it worked.

When the Spanish American War began in 1898, Smith formed his voluntary militia with the approval of the U.S. War Department. Called the Skagway Military Company, Soapy became its captain, strengthening his control of the town.

In the meantime, the vigilante group did not like what they were seeing, and when Soapy’s gang took some $2,600 in gold from a Klondike miner in an illegal Three-card Monte game, the vigilantes re-emerged and demanded that Soapy give him back his gold. Soapy, of course, refused, claiming that the miner had lost the gold “fairly” in a sporting game. The next night, on July 8, 1898, the vigilantes organized a meeting in Skagway, Alaska. Hearing of the meeting, Soapy decided to attend, arriving with a Winchester rifle draped over his shoulder. When he was barred from entering the meeting, he argued with one of four guards, a man named Frank Reid, who was blocking his way.

Before long, a gunfight erupted, and when the smoke cleared, both men lay dead. Soapy’s last words were reportedly: “My God, don’t shoot!” Later, it was found that another one of the guards had shot Smith. Three other members of Soapy’s gang who were involved in “robbing” the miner received jail sentences. The rest of the gang soon drifted apart.

Soapy Smith was buried just outside the city cemetery. His grave and his saloon, which have since been moved from their original location, can still be seen in Skagway.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

“I consider bunco steering more honorable than the life led by the average politician.” — Soapy Smith