Klondike Gold Rush (see below)

Dyea, Alaska – Ghost Town of the Klondike Gold Rush

Seattle & the Klondike Gold Rush

Skagway, Alaska – Jumping Off to the Klondike

Women of the Klondike Gold Rush

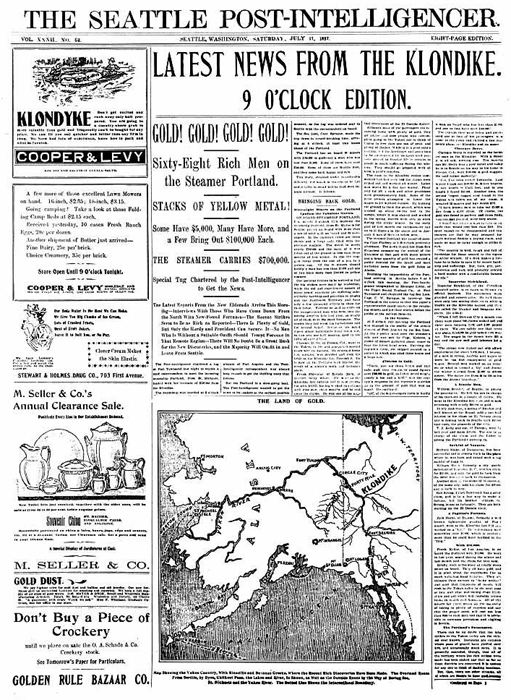

“GOLD! GOLD! The steamer Portland headed for Seattle out of St. Michael, Alaska, steamed down to Seattle this morning with a ton of gold aboard.”

When this magic sentence appeared in the July 17, 1897, issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, it triggered one of the last — and one of the greatest — gold rushes in the history of North America. Before noon that day, every berth aboard the Portland had been sold for the return trip north, and telegraph wires were humming with details of the 68 miners who wrestled their suitcases, gunny sacks, pokes, and jars of gold down the gangplank. When it was weighed, the gold weighed more than two tons. But it didn’t matter by then; the stampede to Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada was on.

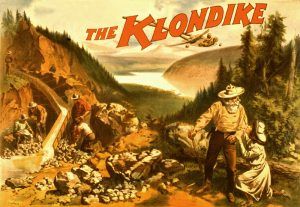

In August 1896, when Skookum Jim Mason, Dawson Charlie, and George and Kate Carmack found gold in a tributary of the Klondike River in Canada’s Yukon Territory, they had no idea they would set off one of the greatest gold rushes in history.

Prospectors had worked in the vast wilderness along the Yukon River for two decades, finding enough “colors” on the feeder streams to buy supplies and tools. But none had made a big strike until these four prospectors stopped to rest beside a tiny stream called Rabbit Creek (now Bonanza Creek), which emptied into the Klondike River. When Skookum Jim Mason, a Tlingit Indian, bent over to get a drink, he saw flecks of gold glistening on the bottom. Prospecting with him were his nephews Dawson Charlie and George Carmack and his wife, Kate, who was also Skookum Jim’s sister. The prospectors gathered the gold dust and soon hurried back to Forty Mile, Yukon, Canada, to file claims. Because Indians were not permitted to stake claims then, George Carmack made the discovery claim for all of them on August 16, 1896. The four then returned to the claim and began to work it. Their find would become known as Discovery Claim and collectively earned nearly one million dollars.

When other prospectors saw Carmack’s gold, they threw their belongings into boats and headed upstream to make claims near the discovery. Immediately the town of Dawson City was established at the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers in Canada. By the winter of 1896, all the good river-bottom claims had been staked by prospectors in the area, and they spent the remainder of the winter and spring digging out their riches from the renamed Bonanza Creek. Another prospector made his way up Eldorado Creek, which fed into the Bonanza, and found more gold, which would prove even richer.

Just before Christmas, word of the gold finds reached Circle City, Alaska. Despite the winter, many prospectors immediately left for the Klondike by dog-sled, eager to reach the region before the best claims were taken. The outside world was still largely unaware of the news, and winter prevented river traffic, so it wasn’t until June 1897 that the first boats carrying the freshly mined gold left the area.

The Klondike Gold Rush was eleven months old when the Portland steamer arrived in Seattle, Washington. The stampede began when that magic message about the “ton of gold” from the Klondike went over the telegraph wires. The mayor of Seattle resigned to organize one of the many ill-fated Klondike mining expeditions. Farmers, bank clerks, teachers, dentists, con men, missionaries, and prostitutes all packed and headed north.

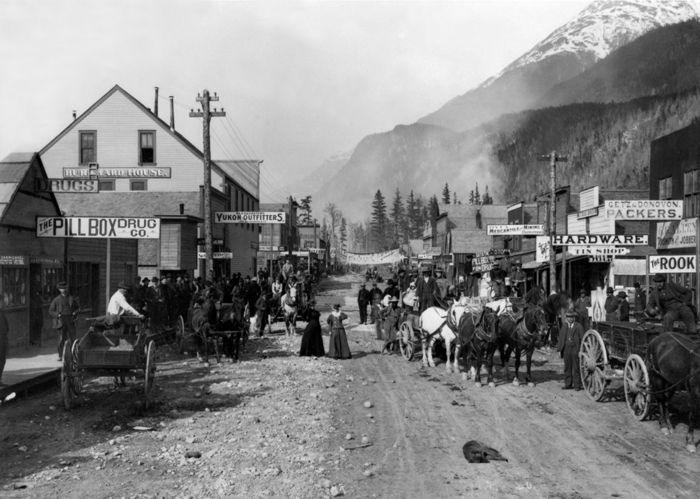

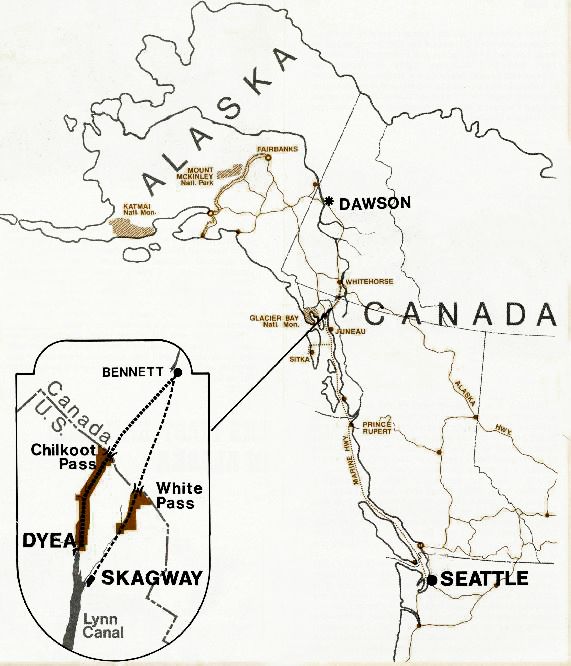

All through the summer and into the winter of 1897-98, hundreds of hopeful gold seekers boarded ships in Seattle and other Pacific port cities and headed northward with the vision of riches and adventure. The stampeders then poured into the newly created Alaskan tent and shack towns of Skagway and Dyea – the jumping-off points for the 600-mile trek to the goldfields. Unfortunately, these prospectors were unaware that most of the good Klondike claims were already staked.

Strangely, another ship with Klondike miners had landed two days ahead of the Portland’s arrival in Seattle. This ship, the Excelsior, went to San Francisco, California, and a crowd watched as the miners disembarked, none carrying less than $5,000 and some with more than $100,000 in gold. Perhaps their arrival wasn’t as well-publicized, or the account of two arrivals within days prompted the stampede to the Klondike.

These many men and women faced their greatest hardships on the Chilkoot Trail out of Dyea and the White Pass Trail out of Skagway. There were murders and suicides, disease and malnutrition, and deaths from hypothermia and avalanches. The Chilkoot Trail was the toughest because pack animals could not be used easily on the steep slopes leading to the pass. Until tramways were built late in 1897 and early 1898, the prospectors had to carry everything on their backs. The White Pass Trail was an animal-killer, as anxious prospectors overloaded and beat their pack animals and forced them over the rocky terrain until they dropped. More than 3,000 animals died on this trail, and to this day, many of their bones still lie at the bottom of Dead Horse Gulch.

“…not one in ten, or a hundred, knew what the journey meant nor heeded the voice of warning.”‘

— Tappan Adney wrote in The Klondike Stampede

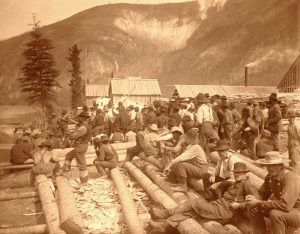

During the first year of the gold rush, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 prospectors spent an average of three months packing their outfits up the trails and over the passes to the lakes. The distance from tidewater to the lakes was about 35 miles, but each individual trudged hundreds of miles back and forth along the trails, moving their gear. Once they had hauled their full array of supplies to the lakes, they built or bought boats to float the remaining 560 or so miles downriver to Dawson City and the Klondike Mining District, where an almost limitless supply of gold nuggets was said to lie.

By the summer of 1898, there were 18,000 people at Dawson City, with more than 5,000 working the diggings. By that time, the best creeks had all been claimed, either by the long-term miners in the region or by the first arrivals of the year before. The Bonanza, Eldorado, Hunker, and Dominion Creeks were all taken, with almost 10,000 claims recorded by July 1898.

By August, many of the stampeders had started for home; most of them broke and disillusioned. The following year saw a larger exodus of miners when gold was discovered at Nome, Alaska. For those who stayed, their wages fell, and the newspapers began to turn against the Klondike Gold Rush.

The great Klondike Gold Rush ended as suddenly as it had begun. Towns such as Dawson City and Skagway began to decline. Others, including Dyea, disappeared altogether, leaving only memories of what many consider to be the last grand adventure of the 19th century.

Over the few short years of the Klondike Gold Rush, an estimated 100,000 prospectors made their way to the Klondike region between 1896 and 1899. Of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people who reached Dawson City, only around 15,000 to 20,000 became prospectors. Of these, no more than 4,000 struck gold, and only a few hundred became rich.

In the end, the four discoverers had mixed fates. George Carmack left his wife Kate, who had found it difficult to adapt to their new lifestyle, remarried, and lived in relative prosperity. Skookum Jim had a huge income from his mining royalties but refused to settle and continued to prospect until he died in 1916. Dawson Charlie spent lavishly and died in an alcohol-related accident.

Today, the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park commemorates the Klondike Gold Rush. Established in 1976, it encompasses 13,191 acres and is the only National Park area established solely to commemorate an American gold rush. The park preserves the historic structures, trails, artifacts, landscapes, and stories associated with the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898.

The National Park is comprised of four units — three in Skagway, Alaska, and the fourth is in Seattle, Washington. Visitors can explore the Skagway Historic District, which includes a visitor center and several museums; the old townsite of Dyea, the gateway to the Chilkoot Trail; and the White Pass Trail.

More Information:

Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park

P.O. Box 517

Skagway, Alaska 99840

907-983-9200

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Dyea, Alaska – Ghost Town of the Klondike Gold Rush

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps Across America

Seattle & the Klondike Gold Rush

Skagway, Alaska – Jumping Off to the Klondike

Sources:

Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park

National Park Service

Wikipedia