By Maggie Van Ostrand

On a sunny afternoon in October 1901 at the bustling Fourth National Bank of Nashville, Tennessee, Spencer McHenry looked up from his work and saw a beautiful woman in fashionable and expensive-looking clothes standing at his teller’s window. Smiling fetchingly, she slid a $500 stack of Bank of Montana notes across the marble counter toward him, and she politely asked if he’d be kind enough to exchange the small bills for large ones. The woman’s name was Annie Rogers.

Little did Annie suspect that bank employees were on the lookout for notes stolen in the Great Northern Train Robbery the previous July. The alert McHenry, who found loyalty to his employer to be more in his character than succumbing to the charms of a beautiful woman, reported his findings to J.T. Howell, the head cashier. Mr. Howell called the police and bank president Samuel J. Keith. Howell and Keith invited Annie Rogers to accompany them into an office, whereupon they told her the bills were stolen.

Faster than a 911 response, detectives Jack Dwyer and Austin Dickens arrived at the bank to question Annie, who denied signing the bills. She insisted that if the bills had been stolen, she surely didn’t know a thing about it.

Pressured by the detectives, Annie finally said a “little blonde man named Charley had given [the bills] to her” in Louisiana. The pair had traveled together for about two weeks from Omaha, Nebraska, to Louisiana, where Charley continued on to New Orleans and Annie to Shreveport. Annie insisted that the $500 was hers, that she had earned it. Dwyer and Dickens would have none of that and took her off to police headquarters to be further questioned by their Lieutenant Marshall.

Annie didn’t even give her name, rank, and serial number. She gave only one of her names, neglecting to tell the dicks that she was also known as Delia Moore or Maude Williams. Other than that, she uttered only the same words about the fictional Charley and repeated that she didn’t know the bills were stolen. This “non-denial denial” caught the attention of Justice Hiram Vaughn, who issued a warrant charging Annie with attempting to pass forged National Banknotes.

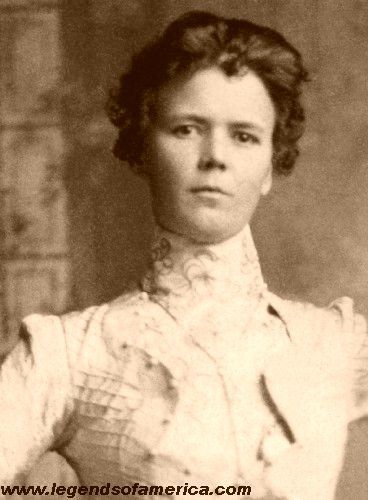

Annie’s arrest was called “one of the most important captures in recent years…” by the Nashville American, which described her as “somewhat good looking, not beautiful but not ugly.” If they printed something like that today, Annie would probably hire a celebrity lawyer and sue their pants off for calling her “not beautiful.” The American went on to say, “She was slender, with a heavy head of dark brown hair, a dark complexion, and high cheekbones. Her most noticeable features were two gold teeth on the left side, and her piercing black eyes … [which] fairly danced as she spoke.”

The same day the American story came out, the Nashville Banner sent a reporter to interview Annie, who cheerfully greeted him as he entered her cell, led by Detective Dwyer. Annie called Dwyer “Happy Jack” and told the reporter he was one of her favorites. It was reported that Annie laughed, smiled, and flirted with her visitor throughout the interview. She regretted, she said, that she hadn’t brushed her hair properly.

The next day, Annie appeared before Justice Vaughn for a preliminary hearing, wearing a black suit and a black hat adorned with ostrich feathers. The Banner reported that “a deep frown gathered her brow and her piercing black eyes danced defiantly in answer to the stares of the onlookers.”

According to Wayne Kindred’s article in a 1995 issue of Old West, the following conversation occurred:

Justice Vaughn asked her if she had heard the warrant read.

“I heard one read yesterday. I don’t know whether it is the same one or not,” she answered.

He told her that it was the same warrant and asked if she wished to plead guilty or not guilty.

“Guilty of what?” she angrily replied. “Of taking those bills to the bank” I took them bills to the bank. Yes, I did that.”

After Justice Vaughn explained the charges again, Annie entered a plea of not guilty. Vaughn then set her bail at $10,000 and asked her if she wanted to make a statement.

“Nothing, but that I came by those bills honestly, and I don’t see why I should be treated this way. I had used some of the bills before, and I thought they were all right.”

The hearing must have seriously scared Annie because, by the next day, she was closer to telling the truth, or so it seemed: her real name was Della Moore, she was 26, and she was born in Tarrant County, Texas.

She left home in 1893 and worked as a prostitute in Mena, Arkansas, Fort Worth, and San Antonio (at the bawdy house of Fannie Porter). Between Ft. Worth and San Antonio, she had married a farmer named Lewis Walker but left him because “he was just a poor farmer,” and their life on the farm was altogether “too tame” for her.

She left Fannie Porter’s house for Colorado, Idaho, and Montana in late 1900 with Bob Nevils, Will Casey, and Lillie Davis (another graduate of Fannie Porter’s “college of soft knocks”). Annie claimed not to have asked either Nevils or Casey what they did for a living. “They were just good fellows,” she said. Nevils gave her five $20 gold pieces on their return to Ft. Worth, where they separated.

Annie split her time between her mother’s Ft. Worth home and Fannie Porter’s house of ill repute in San Antonio. She then left for Mena, Arkansas, where she remained until September 1901. Fannie Porter got word to her that Nevils had come back to San Antonio and wanted Annie to take another trip. Annie responded to the message with a telegram: “Will wait till parties come.” Nevils shortly thereafter came to Arkansas to get her.

According to the Kindred article, their first stop was Shreveport, Louisiana, where they remained for nearly a week, playing cards and patronizing saloons. Nevils had plenty of money and gave Annie a bunch of $10 bills before they left Shreveport for Jackson, Mississippi, where they did “nothing but having a good time.”

They took the day coach to Memphis, Tennessee, and let the good times continue to roll. Annie guessed they spent around $400 having fun, and she especially enjoyed Nevils buying expensive dresses and hats for her. By the time they left Memphis for Nashville on October 10, headed straight for Linck’s Hotel, Annie had Bank of Montana notes for about $400. She must have been a very good companion because Nevils gave her at least another hundred. Perhaps Annie was Mae West’s inspiration when she said: “When I’m good, I’m very, very good, but when I’m bad, I’m better.”

As Annie’s story unfolded, she admitted spending most of her time at the Lincke Hotel in their room, while Nevils preferred hanging around saloons until the wee hours. Then, Annie said, she began to have misgivings. The more money Nevils gave her, the more suspicious she got. She was also afraid he might take the money back and dump her. A shrewd move by Annie was that she changed the money he had given her into larger bills so they could be more easily hidden from him, and repaired to the Fourth National Bank to accomplish this, where she was arrested.

At the completion of this second statement, cops ran to the Linck and found that Nevils, registered under the name R.J. Whalen, had escaped due to the length of time it took Annie to tell her (false) story. She had given him enough time to make his escape. He had checked out the day before taking the train to Birmingham, Alabama, thence on to Mobile, where the cops lost his trail.

An incarcerated Annie Rogers might have been daydreaming of her boring days back on Lewis Walker’s farm. Even that dull life would be better than a dreary jail. On April 21, 1902, she appeared before Judge W.M. Hart asking for a bail reduction. Her former employer, Madame Fannie Porter, who well deserved her kind-though-soiled reputation, offered to put up the money.

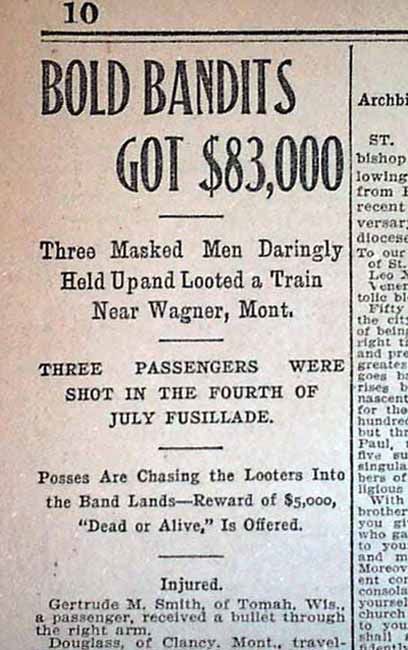

As reported in Kindred’s article, Annie was dressed in a black suit and hat. “Wearing a black glove on one hand and carrying a white handkerchief in the other, she took a seat beside her attorney, Richard West.” Attorney General Robert Vaughn prosecuted his first witness express messenger C.H. Smith who had been brought from Montana to describe the train robbery and link Annie to one of the robbers. He described the robbery ($40,000 in unsigned banknotes on July 3, 1901) near Wagner, Montana, and identified a man in a torn photograph shown him by General Vaughn as one of the train robbers. So ended the first day of Annie’s bail hearing.

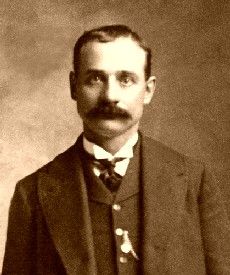

The next morning, a smiling and laughing Annie with the dancing eyes sat in court carrying on a “lively conversation” with a deputy sheriff. She quit laughing as soon as she saw Pinkerton dick Lowell Spence take the stand. General Vaughn showed him the same photograph identified the day before by messenger Smith, and Spence also identified the man as the train robber, one Harvey Logan, member of the Wild Bunch, also called “Kid Curry,” and said he was in the Knoxville, Tennessee, jail. (Note: After he got into a saloon brawl in Pueblo, Harvey and his brothers headed for Hole in the Wall, Wyoming, where they met up with George Curry. Having been known as the “Kid” in Texas, Harvey took George’s last name and began to go by “Kid Curry.”) Logan had been arrested in December 1901 on a charge of felonious assault against policemen. He had over $9,000 of the stolen Bank of Montana bills on him at the time.

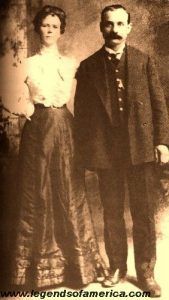

Interestingly, in this damning photograph of Logan, having been identified twice by witnesses, a hand could be seen resting on his left shoulder. In a dramatic moment worthy of Perry Mason himself, General Vaughn whipped out the other half of the picture. The hand was attached to the arm of the defendant, Annie Rogers. Uh Oh. The courtroom sizzled with excitement as observers whispered behind their hands. Then Annie took the stand.

She admitted the man in the photograph was Bob Nevils, but denied ever knowing he was also Harvey Logan or Kid Curry, denied knowing where he got the money, and never heard of the train robbery until her arrest. Judge Hart must not have believed any of these corkers because he proceeded to set bail at $2,500, considerably higher than the $1,000 Annie had requested. Even the indomitable Fannie Porter was unable, or unwilling, to pay such a high bail despite Annie’s tearful entreaties. Sobbing uncontrollably, Annie was led back to her jail cell, where she languished for almost two months until her next day in court.

June 14th saw the same cast of characters in court: defense attorney West, prosecutor Vaughn, and Judge Hart. A plethora of prosecution witnesses were called, including bank employees, hotel employees, and detectives, each telling his tale.

Of these witnesses, the most damning was Corrine Lewis, the pretty owner of a Memphis resort, who also identified the photograph of Logan as one of her hotel guests in September 1901.

He had, said Miss Lewis, “plenty of money,” flashing a large roll of bills. When she asked him if he were not afraid to carry so much money, he said he “wasn’t when he had his guns,” whereupon he tore open his coat, exposing two large revolvers.” Miss Lewis also identified Annie Rogers as Logan’s companion, stating that, although Annie was dressed “plainly” when they arrived, the day after that she had been wearing expensive new clothes. She reported that both Logan and Lewis drank a great deal but never got drunk.

Next up was Annie herself, nervous and pale. She repeated her denials of knowing who Nevils really was, not knowing the money was stolen, and denying that she ever forged the bills. She did, however, admit that she had “bled Nevils and got all the money I could.” She took from him frequently, she said, and had worked him for about $500 by the time they reached Nashville. Annie then stepped down from the witness stand.

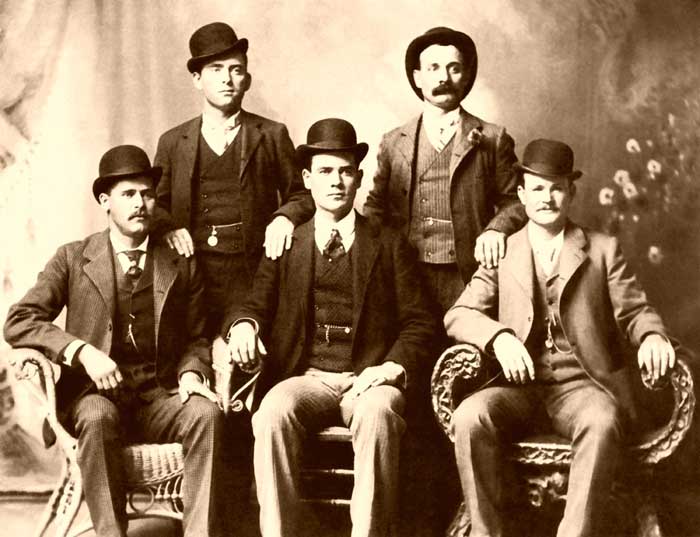

Wild Bunch, aka: Hole in the Wall Gang (1896-1901) – Led by Butch Cassidy, the Wild Bunch terrorized the states of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada for five years.

Backing her up was a deposition from Harvey Logan, read by defense attorney West. In it, Logan, at the Knoxville jail, said he had been with Annie at Linck’s Hotel the day she was arrested and that she had left him in mid-afternoon. When she didn’t return, Logan “thought that she had quit me.” He said that he had given her the money and that it was signed before she got it.

In their closing arguments, prosecutor Vaughn called her a greedy opportunist, a liar, and accused her of aiding and abetting Logan’s escape. Defense attorney West said she was just an unsophisticated country girl who had been duped by a clever criminal.

The jury came back to a packed courtroom with a verdict in fewer than two hours. “Not guilty!!” A relieved and thrilled Annie Rogers shook hands with each jury member, her lawyer, and the judge. Spectators crowded around her, voicing their approval of the verdict, while Annie expressed pleasure at being given a “fair deal.”

Annie then asked for her $500 back, claiming it was her money after all, but the court eventually ruled that she was not entitled to it.

Annie left Tennessee and returned to Texas, where she followed Logan’s exploits in the papers and wrote to him. Logan was captured in Jefferson City following a fight in a Knoxville saloon where he broke a man’s nose in a quarrel and shot two Knoxville Police Officers who opened fire on him.

Pinkerton Agents aggressively pursued the members of the Wild Bunch.

Logan was subsequently tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in Tennessee Prison. Using wire from a jailhouse broom, Logan engineered his escape from the Knox County jail. He killed himself a few months later after a failed bank robbery.

The members of the Wild Bunch were aggressively pursued by Pinkerton Agents.

During his lifetime, Logan/Kid Curry was wanted on warrants for fifteen murders, but it was generally known that he had killed more than twice that number. William Pinkerton, head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, called Kid Curry the most vicious outlaw in America. “He has not one single redeeming feature,” Pinkerton wrote. “He is the only criminal I know of who does not have one single good point.”

There exists no evidence that Annie ever saw Logan again, and it is surmised she changed her name once more and went back to work at Fannie Porter’s.

© Maggie Van Ostrand, updated November 2022.

About the Author: Maggie Van Ostrand’s articles have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Boston Globe, various magazines; monthly in the Mexican publication, El Ojo Del Lago and mexconnect.com, and numerous contributions to Texas Escapes Online Magazine, from which this article was provided.

Also See:

Butch Cassidy & the Wild Bunch

Hole in the Wall – Outlaw Hideout

Harvey Logan, aka “Kid Curry” – The Wildest of the Wild Bunch