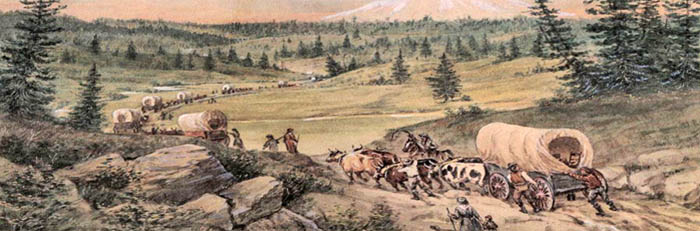

The average overland journey took between four to five months in a covered wagon.

After crossing the Rocky Mountains and entering present-day Idaho, the emigrants in the early 1840’s considered themselves officially in Oregon Territory.

Some families took along livestock to supplement their food along the trail, including goats, cows, and chickens. They also brought along preserved foods.

Wagon trains lumbered over the ground at a speed of between one and two miles per hour, making progress between 10 and 15 miles per day.

Before 1834 there were no trading posts between Missouri and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Walla Walla, Washington.

Most emigrants walked the entire distance of the trail, many of them barefoot at times.

By 1843 the “Oregon fever” had spread among farmers suffering from hard times. They formed societies to plan the trip, and in the spring, a party of 1000 pioneers heads west from Independence, Missouri. It is known as “The Great Migration.”

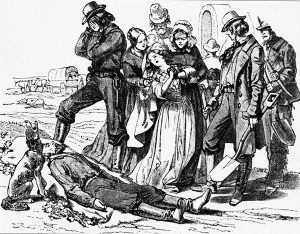

There were more fatalities from the accidental discharge of guns than from confrontations with Indians.

Up till 1849, a hired trail guide was deemed essential to a wagon train’s success. However, after the trails became more defined and trail traffic became heavier, guides were no longer necessary.

Commencement of the overland journey usually occurred during a five-week window from the last week of April through the end of May. If they left too early, there would be no grass for their animals to eat; if they left too late, they would get caught by the winter snow.

From 1841 through 1865, there were 172 murders along the trails as pioneers killed each other. While most of the perpetrators were unidentified and escaped punishment, 21 reported murder trials resulted in executions on the trail.

Mass migration over the Oregon Trail by wagon was only made possible after a wide gap through the Rocky Mountains, called South Pass in present-day Wyoming, was identified in 1824.

Most wagon trains generally consisted of 20 to 40 wagons, making them more manageable than larger wagon trains.

The greatest percentage of overlanders came from Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana.

Sixty percent of the overland travelers were farmers.

The Oregon, California, and Mormon Pioneer Trails followed the general path of the Platte River for 450 miles.

In 1839 the first farmers, a group of 13 men from Illinois, traveled the Oregon Trail led by Thomas Farnham reached Oregon with packhorses.

Astronauts are said to make out two manmade objects from space: the Great Wall of China and the traces of the Oregon Trail.

The covered wagons used on the trail had no suspension, and the trail was uneven, rough, and rocky. They were so uncomfortable that many people preferred to walk unless they had horses to ride.

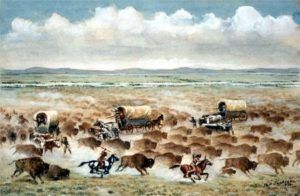

Food supplies were supplemented by hunting and fishing. Buffalo, wild game, elk, deer, and small game such as rabbits and squirrels offered welcome meat supplies. Fish included salmon and trout.

An estimated 34,000 to 45,000 lives were lost along the Oregon Trail. That’s between 17 to 22 lives per mile.

Just 20 percent of the historic ruts created by the steady wear of wagon wheels along the Oregon Trail remain identifiable today.

Outfitting a family of four, including wagon, animals, and provisions cost between $500 and $1,000. In today’s dollars, that would be between $7,986 and $15,972. Emigrants often had to save from one to three years’ wages to afford the trip.

There are some 200 known graves along the Oregon Trail. Most are unmarked. To protect the graves of their loved ones from being disinterred, the dead were often buried directly under the path of the trail. Wagons passing over would help to obliterate any sign so the graves could not be detected.

It is estimated that one out of every 250 emigrants kept diaries or journals while heading west.

The boat-shaped Conestoga wagons were rarely used on the Oregon Trail.

The first third of the Oregon Trail was geographically the easiest, but it was also the most disease-ridden. Finally, the last third of the trail was the most physically challenging due to the terrain.

American Indians were usually among the least of the emigrants’ problems. In fact, emigrants killed more Indians than the natives killed pioneers.

By 1899 all Native American tribes in Oregon were on government-designated reservations.

Migration was spurred by the panic of 1837, which brought hard times to midwestern farmers.

Between 1841 and 1866, an estimated 500,000 emigrants headed west over the trail.

About 10% of the pioneers died on the journey accounting for approximately 50,000 deaths,

The number one killer on the Oregon Trail, by a wide margin, was disease and serious illnesses. Of these, cholera was the disease that killed most travelers.

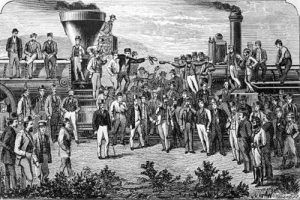

The Transcontinental Railroad follows the same path as the Oregon Trail along much of its distance.

In 1842, the first emigrant to die from a firearm accident on the Oregon Trail was ironically named John Shotwell. Unfortunately, he made the fatal mistake of getting his gun out of his wagon muzzle first.

Once the emigrants left the plains and began their ascent through the mountains, the trail became littered with treasured heirlooms and keepsakes deemed too heavy to transport any further.

Oregon Trail famous pioneer, Ezra Meeker, made the trip dozens of times

A few emigrants en route had quite the surprise when they climbed up trees to view what they thought were eagle nests. It was the custom of some Indian tribes to bury their dead up in scaffolds in the trees to be closer to the spirit world.

The army sent out soldiers on the Oregon Trail as early as 1845 to retrieve individuals attempting to flee from their debts.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 mostly brought an end to the wagon-train era. However, as late as 1895, covered wagons could still be seen heading west.

The first place in which the Oregon Trail split was at the “Parting of the Ways” was in south-central Wyoming. The left fork headed to Utah and California, and the right fork was the Sublette Cutoff, which headed to Oregon. The second place where the Oregon Trail split was just past Soda Springs, Idaho. The left fork took the Hudspeth Cutoff heading to California, and the right fork continued to Oregon.

Meals for travelers commonly consisted of bacon, beans, and coffee, with biscuits or bread. There was little fruit containing Vitamin C that led to the disease of scurvy.

In 1978, Congress designated the 2,000-mile trail as the National Historic Oregon Trail.

Compiled by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated July 2022.

Also See:

Oregon-California Trail Timeline

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Oregon-Mormon-California-Pony Express Trails Photo Gallery

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Sources:

American Historama

Author Talk

Facts For Now

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West