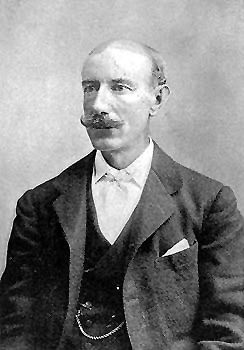

Though one of the most impressive visitors to Estes Park, Colorado in the 19th century, Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quinn, or the Earl of Dunraven, was much hated by many of the area settlers as he made plans to own all of beautiful Estes Park.

The Irish aristocrat was a world traveler and sportsman and he first made his way to the Estes Valley of Colorado in 1872. By 1874, Dunraven had claimed 8,000 acres in Estes Park and the future site of Rocky Mountain National Park. The land was obtained by both legal and questionable means.

Earl Dunraven was born on February 12, 1841, to the 3rd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl and Florence Augusta Goold. He was educated at Christ Church in Oxford, England. Afterward, he served in the military and at the age of 26, became a correspondent for the London newspaper, the Daily Telegraph.

He married Florence Kerr in 1869, and the two honeymooned in New York and Virginia. The couple would have four children.

Earl Dunraven spent much of his leisure time hunting wild game in various parts of the world and after hearing of the fine hunting in the American West, he decided to visit. He made his first hunting trip in the autumn of 1871. With none other than Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro acting as his guides, they hunted elk along the North Platte River in Wyoming. The Earl traveled in style, even bringing a personal physician, Dr. George Henry Kingsley.

In 1872, 31-year-old Earl Dunraven returned to hunt, this time in Nebraska, Wyoming, and in Colorado’s South Park. While relaxing among the nightspots of Denver, the Earl met Theodore Whyte. Mr. Whyte, then 26-years-old, had arrived in Colorado during the late 1860s. Originally from Devonshire, England, he had trapped for the Hudson’s Bay Company for three years and had tried his hand in the Colorado mines.

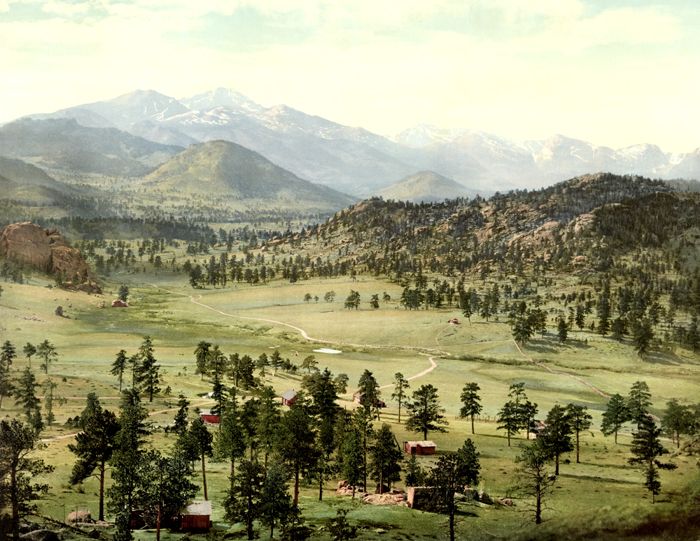

During some of his earlier rambles, Whyte became familiar with Estes Park. Whyte sang the praises of the area, telling the Earl about the abundance of deer, elk, and bear just perfect for “sport.” But very little convincing was necessary. Soon the Earl and a few friends were heading into the foothills, following the crude cattle trail leading toward Estes Park. Though it was bitterly cold, they arrived on December 27th. They stayed with Griff Evans, another of their countrymen, and a man eager to please the nobility of his homeland. In the ensuing days, the Earl hunted elk in Black Canyon, along the Fall River, and in the Bear Lake area.

In 1874, he traveled to the Yellowstone country for hunting and wrote a perceptive book, The Great Divide, covering not only his hunting experiences but also a description of the geology, the Indians, and the gold mining towns of the area. He then made his way to Estes Park for more hunting.

Obviously, the Earl loved the area for both its beauty and its “sporting” opportunities. He returned in 1874, writing:

“The air is scented with the sweet-smelling sap of the pines, whose branches welcome many feathered visitors from southern climes; an occasional humming-bird whirrs among the shrubs, trout leap in the creeks, insects buzz in the air; all nature is active and exuberant with life. The climate is health-giving, unsurpassed (as I believe) anywhere …none can appreciate it except those who have had the good fortune to experience it themselves.”

Reuniting with Texas Jack in 1874, he explored Yellowstone Park and documented it in his book Hunting in the Yellowstone.

Later on the same trip, the young earl decided to make the whole of Estes Park, Colorado into a game preserve for the exclusive use of himself and his British and Irish friends. By stretching the provisions of the Homestead Act and pre-emption rights, which allowed settlers’ to purchase public lands, Dunraven secured 8,000 acres. The land was very strategically chosen along stream courses radiating out from the Estes Park Valley so that, though he owned only 8,000 acres, in effect he controlled nearly 15,000 acres.

Assisted by his new friend Theodore Whyte and several Denver bankers and lawyers, the Earl first arranged to have the park legally surveyed. Once that formality was accomplished, the Earl and his agents used a scheme, common among other speculators, exploiting the Homestead Law to their advantage. They found local men in Front Range towns willing—for a price—to stake 160-acre claims throughout the park. More than 35 men filed claims using this ploy. Then, Dunraven’s “Estes Park Company, Ltd.”(or the English Company as it was called locally) proceeded to buy all those parcels at a nominal price, estimated at five dollars per acre. Between 1874 and 1880, the Earl managed to purchase 8,200 acres of land. In addition, the Company controlled another 7,000 acres because of the lay of the land and the ownership of springs and streams.

His efforts resulted in what has been called “one of the most gigantic land steals in the history of Colorado.” Thirty-one claims were filed for his use of the land and a grand jury was set to investigate his claims. The legal wrangling lasted for years.

Denver newspapers reported in July 1874 that a sawmill would be built, Swiss cattle were to be introduced, ranching would be expanded, and a hunting lodge would be constructed in Dunraven Glade on the North Fork of the Big Thompson River. Theodore Whyte was chosen to serve as the Earl’s agent and manager in Colorado.

Griff Evans, with whom the Earl had stayed within 1872, was one of the first to sell out. Bitterness developed between those settlers who had no intention of selling and the powerful forces of the English Company. Reverend Elkanah Lamb, who had homesite just east of Longs Peak, loudly voiced his disgust at those who sold out. Many years later, the Reverend Lamb would say:

“Griff Evans, being of a good-natured genial turn of mind, liking other drinks than water and tempted by the shining and jingle of English gold, Dunraven very soon influenced him to relinquish his claim and all of his rights in the park for $900.”

Lamb also believed that the Earl’s land-grabbing was fraudulent and also said:

“Dunraven picked up men of the baser sort, irresponsible fellows not regarding oaths as of much importance when contrasted with gold.”

Those who cooperated with the Earl, according to Reverend Lamb,

“prepared to sell their souls for a mess of pottage at the dictation of a foreign lord.”

Bitterness led to outright confrontations and violence became inevitable. One man who loudly opposed the Earl was James Nugent, better known as Rocky Mountain Jim. Like other squatters in the area, Jim trapped for a living and also kept a small herd of cattle. However, he controlled some very important real estate. His cabin sat at the head of Muggins Gulch, dominating the main entrance to Estes Park. Ill feelings began to develop between Griff Evans and Mountain Jim. On June 19, 1874, Griff Evans shot Jim Nugent. There were a number of versions told regarding the shooting.

Reverend Lamb, clearly hostile to the Earl, argued that Jim asked for trouble when he “declined to permit this fraternity of English snobs and aristocrats to pass through his sacred precincts any more, there being at the time no other way in or out of the Park.”

Earl Dunraven said: “Evans and Jim had a feud, as per usual about a woman—Evans’ daughter.”

Jim was critically injured but was not dead. In fact, he lived for another three more months, lingering with a pellet lodged in his brain. He died in September.

Griff Evans was arrested and charged with the shooting but the case was dismissed for lack of witnesses. On Evans release, the Earl interpreted “the result of the verdict to the effect that Evans was quite justified, and that it was a pity he had not done it sooner.”

In the end, it really didn’t matter whether it was land ownership or a personal squabble that led to Mountain Jim’s death; he was conveniently removed from the scene. He was only a minor annoyance as the English Earl had plenty of power to continue with his plans. But the arrival of more settlers to the area continued to dispute the English Company’s claims.

At about the same time, Abner E. Sprague and his partner Clarence Chubbuck built a cabin in Moraine Park. They were also squatters on the public domain. Together they joined a handful of settlers willing to challenge the Earl of Dunraven’s claim to most of Estes Park. Chubbuck was murdered in 1875 during a cattle roundup out on the plains.

In the autumn of 1876, the Earl again returned to Estes Park, this time bringing the noted artist Albert Bierstadt, who he had commissioned to paint a large landscape of Estes Park and Longs Peak. Once completed, the Earl reportedly paid Bierstadt $15,000 and the painting was transported to Europe to adorn the walls of Dunraven Castle.

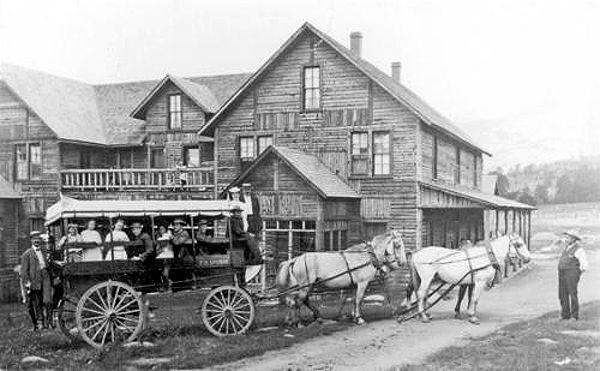

While in the area, Bierstadt was also asked to use his artistic eye to help select a site for the Earl’s hotel. Dunraven made his decision and had the wealth to ensure speedy construction. Bierstadt recommended a site on the eastern side of Estes Park, near Fish Creek. Work quickly began on the Estes Park Hotel, which was called “The English Hotel” by the locals. The three-story, timber-framed hotel opened in the summer of 1877. Situated in a meadow east of the present Estes Park village, it was the first strictly tourist hotel built in the Park.

The hotel was successful but the people of the area continued to dispute Dunraven’s claims and he was in constant litigation. The Earl made his last visit to Estes Park in 1882. He would later say:

“People came in disputing claims, kicking up rows: exorbitant land taxes got into arrears, and we were in constant litigation. The show could not be managed from home, and we were in constant danger of being frozen out. So we sold for what we could get and cleared out, and I have never been there since.”

The Earl sold his land to F.O. Stanley and B. D. Sanborn in 1907. Stanley built the now-historic Stanley Hotel.

Dunraven’s wooden “English Hotel” burned to the ground in 1911.

Interestingly, the Earl had written approvingly about the preservation of Yellowstone as a national park for the enjoyment of the general public but ironically didn’t see the same ideals for the land that he wished to preserve only for himself and a few friends.

The Rocky Mountain National Park was established in 1915.

In the meantime, Earl Dunraven was involved in politics in England and wrote several books. He died n June 1926 at the age of 85.

Today, he is considered a hero and villain depending on who you ask. Mount Dunraven in Rocky Mountain National Park and Dunraven Pass in Yellowstone National Park were named for him.

The Albert Bierstadt painting of Estes Park is now held in the Denver Public Library’s art collection.

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated February 2020.

Also See:

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Rocky Mountain National Park Photo Gallery

Check out this guide to the best Rocky Mountain National Park Hikes from 10 Adventures!

Sources: