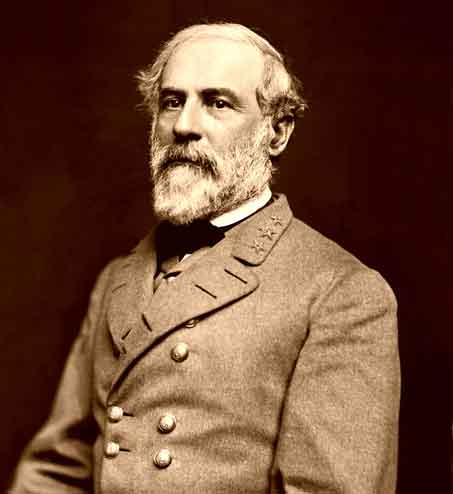

Robert E. Lee

By Charles Morris, 1899

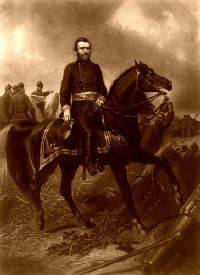

President Abraham Lincoln was delighted with the Savannah, Georgia victory as a Christmas present: In his congratulatory letter to Generals William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant, the Commander in Chief said he would leave the war’s final phases to his two leading professional soldiers. Accordingly, from City Point, on December 27, 1864, Grant directed Sherman to march overland toward Richmond, Virginia. At 3:00 p.m. on December 31, Sherman agreed to execute this last phase of Grant’s continental sweep. In the final 100 days of the war, the two generals would demonstrate the art of making warfare principles come alive and prove that each principle was more than a platitude. The commanders had a common objective: Ulysses S. Grant and George Meade would continue to hammer General Robert E. Lee. Sherman was to execute a devastating invasion northward through the Carolinas toward a juncture with Meade’s Army of the Potomac, then on the line of the James River. Their strategy was simple. It called for the massing of strength and exemplified an economy of force.

It would place Lee in an untenable position, cutting him off from all other Confederate commanders and trapping him between two Union armies. A surprise would be achieved by reuniting Sherman’s original corps when John Schofield, moving from central Tennessee by rail, river, and ocean transport arrived at the Carolina capes. Based on a centralized logistical system with protected Atlantic supply ships at their side, Grant and Sherman were ready to end Lee’s stay in Richmond.

Robert E. Lee, the master tactician, divining his end, wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that the Confederates would have to concentrate their forces for a last-ditch stand. In February 1865, the Confederate Congress conferred all Confederate armies’ supreme command on Lee, an empty honor. Lee could no longer control events. Sherman moved through Columbia, South Carolina, in a destructive campaign much harsher than that visited Georgia. Even the Union troops felt South Carolina had started the war and should be punished. Sherman took Wilmington, North Carolina, the Confederacy’s last available port, in February and then pushed on. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, newly reappointed to command, had the mission of stopping Sherman’s forces but could not. He interposed his small army of about 21,000 effectively in the path of two of Sherman’s corps at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19, 1965. His initial attack gained ground, but by the next day, more of Sherman’s forces were on the scene, and Johnston had to continue his retreat.

Burning of Columbia, South Carolina

There would be no further significant attempts to stop Sherman. At Richmond and Petersburg toward the end of March, Grant renewed his efforts along a 38-mile front to get at Lee’s right (west) flank. By now, Sheridan’s cavalry and the VI Corps had returned from the Shenandoah Valley, and the total force immediately under Grant numbered 101,000 infantry, 14,700 cavalry, and 9,000 artillery. Lee had 46,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 5,000 artillery.

On March 29, Grant began his move to the left. Sheridan and the cavalry pushed out ahead by way of Dinwiddie Court House to strike at Burke’s Station, the intersection of the Southside and Danville Railroads, while Grant’s main body moved to envelop Lee’s right. But Lee, alerted to the threat, moved west. Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill, who never stood on the defense if there was a chance to attack, took his corps out of its trenches and assaulted the Union left in the swampy forests around White Oak Road. He initially pushed Major General Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps back, but Warren counterattacked and, by March 31, had driven Hill back to his trenches. On that day, Sheridan advanced toward Five Forks, a road junction southwest of Petersburg, and there encountered a strong Confederate force — cavalry plus two infantry divisions under Major General George E. Pickett — which Lee had dispatched to forestall Sheridan. Pickett attacked and drove Sheridan back to Dinwiddie Court House, but Sheridan dug in and halted him there.

Pickett then entrenched at Five Forks instead of pulling back to make contact with Hill, whose failure to destroy Warren had left a gap between him and Pickett, with Warren’s corps in between. Sheridan, still formally the commander of the Army of the Shenandoah, had authority from Grant to take control of any nearby infantry corps of the Army of the Potomac. He wanted Warren to fall upon Pickett’s exposed rear and destroy him, but Warren moved too slowly, and Pickett consolidated his position. On April 1, Sheridan attacked again but failed to destroy Pickett because Warren had moved his corps too slowly and put most of it in the wrong place. However, the Union attack struck Pickett’s position in full force on both flanks late afternoon. His position outflanked, Pickett ordered a retreat, but not quickly enough to avoid losing almost half his force of 10,000 as prisoners.

Grant renewed his attack against Lee’s right on April 2. The assault broke the Confederate line and forced it back northward. The Federals took the line of the Southside Railroad, and the Confederates withdrew toward Petersburg. Lee then pulled General James Longstreet’s corps away from the shambles of Richmond to hold the line, and in this day’s action, General Hill was killed. With his forces stretched thin, Lee abandoned Richmond and the Petersburg fortifications. He struck out and raced west toward the Danville Railroad, hoping to get to Lynchburg or Danville, break loose, and eventually join forces with Johnston. But Grant had Lee in the open at last. He pursued relentlessly and speedily, with troops behind (east of) Lee and south of him on his left flank, while Sheridan dashed ahead with the cavalry to head Lee off. A running fight ensued from April 2-6. Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s corps was surrounded and captured at Sayler’s Creek. Lee’s rations ran out; his men began deserting and straggling. Finally, Sheridan galloped his men to Appomattox Court House, squarely athwart Lee’s line of retreat.

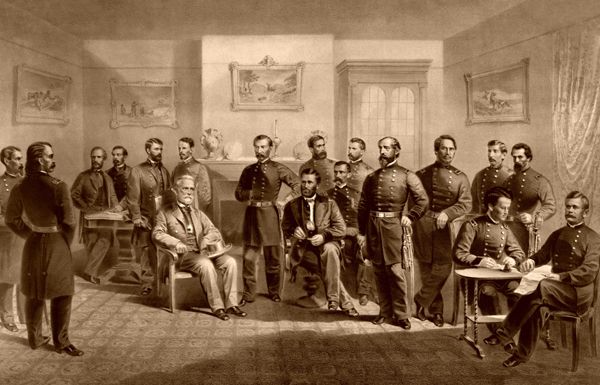

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrenders to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, by Major and Knapp

Lee resolved that he could accomplish nothing more by fighting. He met Grant at the McLean House in Appomattox on April 9, 1865. The handsome, well-tailored Lee, the epitome of Southern chivalry, asked Grant for terms. Reserving all political questions for his own decision, Lincoln had authorized Grant to treat only purely military matters. Though less impressive in his bearing than Lee, Grant was equally chivalrous. He accepted Lee’s surrender, allowed 28,356 paroled Confederates to keep their horses and mules, furnished rations to the Army of Northern Virginia, and forbade the Army of the Potomac soldiers to cheer or fire salutes to celebrate the victory over their old antagonists. Johnston surrendered to Sherman on April 26. The last major Trans-Mississippi force gave up the struggle on May 26, and the grim fighting ended.

Compiled & edited Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023. Source: Morris, Charles; A New history of the United States: The greater Republic; 1899

Also See: