Los Angeles History

Though the city of Los Angeles, California, is the second-largest metropolitan area in the United States, with almost four million souls, it is a relatively young city, not founded until the mid-nineteenth century.

Several Indian tribes, including the Tongva, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay, and Chumash, active in fine boatbuilding first inhabited the area. The first explorer known to the area was Juan Cabrillo, who stopped at present-day San Pedro in 1542, greeted by Tongvan men, who rowed out to meet his ship. The explorer died later that year while wintering at Santa Catalina Island, and no white face was seen again locally for 227 years.

The Spanish conquest of Mexico reached the area in 1769, and in 1771 they founded the Mission San Gabriel Archangel, one of eight missions established by the Franciscans in Southern California.

For years, history has told that on September 4, 1781, 44 “pobladores” who were recruited from northern Mexico to help cement Spain’s control over Alta, California (Upper California), established the settlement. Only two of these settlers identified as Spaniards; the rest came primarily of African or Indian descent. However, scholars have uncovered over the past few decades that the pobladores arrived separately, some as early as June. (September 4 remains the traditional celebrated anniversary).

The small town received the name El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles de la Porciuncula, “The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels.” The settlement became a cattle ranching center located on the Los Angeles River. The oldest house in Los Angeles County was built in 1795 on what became the Rancho San Antonio. It is now known as the Henry Gage Mansion in Bell Gardens.

At the time of the arrival of Spanish missionaries, an estimated 5,000 Tongvan Indians were living in 31 known village sites. In common with other California tribes in the mission system, the Tongva allowed the missionaries to convert and civilize them. Native religious and hunter-gatherer practices were redirected into Roman Catholicism and agriculture. Though destructive of their culture, the mission system valued the individual Native Americans and employed them on the mission farms and ranches. When the missions were disbanded, the natives were thrown back on their much-reduced resources. The Tongva tribe still exists, with perhaps a few thousand members but no reservations.

Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821 did not change life in Los Angeles other than to allow the secularization of the missions, where land grants distributed the mission properties to rancheros.

In 1842, a shepherd discovered gold in Placerita Canyon, just outside the current city limits, sparking a minor gold rush. In subsequent decades, mining became an important industry, employing hard rock and placer techniques. The local mountains are still riddled with abandoned mines, and hopeful prospectors in the San Gabriel River still pan for gold.

Manifest Destiny reached California during the Mexican-American War (1846 – 1848). On June 18, 1846, a small group of Yankees raised the California Bear Flag and declared independence from Mexico. United States troops quickly took control of the presidios at Monterey and San Francisco and proclaimed the conquest complete.

In Southern California, the Mexicans, for a time, repelled American troops, but Los Angeles eventually fell to Lieutenant Colonel John C. Fremont. The United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Capitulation at Cahuenga Pass on January 13, 1847.

April 4, 1850, saw the incorporation of Los Angeles as a city. At the same time, the old landowners started to lose their lands. Compelled to secure confirmation of their land grants in U.S. courts, ten percent of the bona fide landowners of Los Angeles County had to move off their land and were reduced to bankruptcy.

Other Mexican residents resisted the new Anglo powers by resorting to social banditry against the gringos. In 1856, Juan Flores threatened Southern California with a full-scale Mexican revolt. He was hanged in Los Angeles in front of 3,000 spectators. Tiburcio Vasquez, a legend in his own time among the Mexican population for his daring feats against the Anglos, was captured in what is believed to be present-day West Hollywood. The bandit was found guilty of two counts of murder by a San Jose jury trial in 1874 and was hanged in that location in 1875.

The thriving Chinatown was the site of terrible violence in 1871. A Tong war between rival gangs resulted in the accidental death of a white man. This enraged the white populace, and a mob of 500 men descended on Chinatown. They killed 19 men and boys, only one of whom had been involved in the original killing, as well as a white man who tried to protect them. Homes and businesses were looted. A grand jury investigation followed, but only one man served prison time.

In the 1870s, Los Angeles was still little more than a village of 5,000. By 1900, there were over 100,000 occupants in the city. Several men actively promoted Los Angeles, working to develop it into a great city and to make themselves rich. Angelenos set out to remake their geography to challenge San Francisco with its port facilities, railway terminal, banks, and factories.

In 1871, Phineas Banning excavated a channel out of the mudflats of San Pedro Bay leading to Wilmington. Banning had already laid track and shipped in locomotives to connect the port to the city. Harrison Gray Otis, founder and owner of the Los Angeles Times, and several business colleagues began reshaping southern California by expanding it into a harbor at San Pedro using federal dollars.

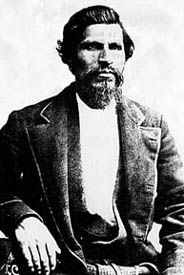

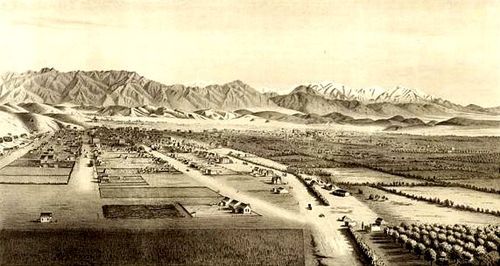

Los Angeles, 1873

This put them at odds with Collis P. Huntington, president of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company and one of California’s “Big Four” robber barons.

The line reached Los Angeles in 1876, and Huntington directed it to a port at Santa Monica, where the Long Wharf was built. The San Pedro forces eventually prevailed, although it required Banning to turn his railroad over to the Southern Pacific Railroad. Work on the San Pedro breakwater began in 1899 and was finished in 1910. Otis Chandler and his allies secured a change in state law in 1909 that allowed Los Angeles to absorb San Pedro and Wilmington, using a long, narrow land corridor to connect them with the rest of the city.

Edward L. Doheny discovered oil in 1892 near the present location of Dodger Stadium. Los Angeles became a center of oil production in the early 20th Century, and by 1923, the region was producing one-quarter of the world’s total supply. Today, it is still a significant producer.

To sustain future growth needed, new sources of water. The only local water in Los Angeles was the intermittent Los Angeles River, and the area’s minimal rain replenished groundwater. Legitimate concerns about water supply were exploited to gain backing for a huge engineering and legal effort to bring more water to the city and allow more development. Two hundred and fifty miles northeast of Los Angeles in Inyo County, near the Nevada line, a long, slender desert region known as the Owens Valley had the Owens River, a permanent stream of fresh water fed by the melted snows of the Sierra Nevada that collected in the shallow, saline Owens Lake, where it evaporated.

Sometime between 1899 and 1903, Harrison Gray Otis and his son-in-law’s successor, Harry Chandler, led successful efforts to buy cheap land on the northern outskirts of Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley. At the same time, they enlisted the help of William Mulholland, Chief of the Los Angeles Water Department, and J.B. Lippincott of the United States Reclamation Service. Lippencott performed water surveys in the Owens Valley for the Service while secretly receiving a salary from the City of Los Angeles. He persuaded Owens Valley farmers and mutual water companies to pool their interests and surrender the water rights to 200,000 acres of land to Fred Eden, Lippincott’s agent and a former mayor of Los Angeles.

Eden then resigned from the Reclamation Service, took a job with the Los Angeles Water Department as an assistant to Mulholland, and turned over the Reclamation Service maps, field surveys, and stream measurements to the city. Those studies served as the basis for designing the longest aqueduct in the world.

By July 1905, Chandler’s L.A. Times began to warn the voters of Los Angeles that the county would soon dry up unless they voted bonds for building the aqueduct. Artificial drought conditions were created when water was run into the sewers to decrease the reservoir supply, and residents were forbidden to water their lawns and gardens. On election day, the people of Los Angeles voted for $22.5 million worth of bonds to build an aqueduct from the Owens River and defray other project expenses. With this money and a special Act of Congress allowing cities to own property outside their boundaries, the City acquired the land that Eden had acquired from the Owens Valley farmers and started to build the aqueduct. On the occasion of the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct on November 5, 1913, Mullholland’s entire speech was five words: “There it is. Take it.”

The City of Los Angeles remained within its original 28 square-mile land grant until the 1890s. The first significant additions to the city were the districts of Highland Park and Garvanza to the north and the South Central area. In 1906, the approval of the Port of Los Angeles and a change in state law allowed the city to annex the Shoestring, a narrow and crooked strip of land leading from Los Angeles south towards the port. The port cities of San Pedro and Wilmington were added in 1909, and the city of Hollywood was added in 1910, bringing the city up to 90 square miles.

The opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct provided the city with four times as much water as it required, and the offer of water service became a powerful lure for neighboring communities. The City was saddled with a large bond and excess water, locked in customers through annexation by refusing to supply other communities. Otis Chandler, a significant San Fernando Valley real estate investor, used his Los Angeles Times to promote development near the aqueduct’s outlet. By referendum of the residents, 170 square miles of the San Fernando Valley and the Palms district were added to the city in 1915, almost tripling its area, mostly towards the northwest. Over the next few decades, dozens of additional annexations were made to the city.

At about the same time, motion picture production companies from New York and New Jersey started moving to sunny California because of the good weather. Although electric lights existed then, none were powerful enough to adequately expose film; natural sunlight was the best illumination source for movie production. Besides the moderate, dry climate, they were also drawn to the state because of its open spaces and natural scenery.

Another reason was the distance between Southern California and New Jersey, which made it more difficult for Thomas Edison to enforce his motion picture patents. Edison owned almost all the patents relevant to motion picture production at the time. In the East, Edison and his agents often sued movie producers acting independently of Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company. Thus, movie makers working on the West Coast could work independently of Edison’s control. If he sent agents to California, word would usually reach Los Angeles before the agents did, and the movie makers could escape to nearby Mexico. Before long, dozens of film studios were established in the Nevada district.

Los Angeles continued to spread out, particularly with the development of the San Fernando Valley and the building of the freeways launched in the 1940s. When the local streetcar system went out of business, Los Angeles became a city built around the automobile, with all the social, health, and political problems produced by this dependence.

Amid all this road building, Route 66 was commissioned in 1926 and would change dozens of times through the next several decades as Los Angeles continued to grow and expand.

During World War II, Los Angeles became a center for producing aircraft, war supplies, and munitions. Thousands of African Americans and white Southerners migrated to the area to fill factory jobs.

Panorama at Broadway Street and Temple Streets in downtown Los Angeles shows the Hall of Justice, the post office, City Hall, and the Hall of Records, 1946.

By 1950, Los Angeles was an industrial and financial giant created by war production and migration. Los Angeles assembled more cars than any city other than Detroit, Michigan, and made more tires than any city. Still, Akron made more furniture than Grand Rapids and stitched more clothes than any city except New York. In addition, it was the national capital for the production of motion pictures, radio programs, and, within a few years, television shows. Construction boomed as tract houses were built in ever-expanding suburban communities financed primarily by the Federal Housing Administration.

Los Angeles’s famed urban sprawl became a notable feature, and growth accelerated in the first decades of the 20th century. The San Fernando Valley, sometimes called “America’s Suburb,” became a favorite site of developers, and the city began growing past its roots downtown toward the ocean and toward the east.

Today, the metropolitan area encompasses 469 square miles and five counties.

Route 66

With the advent of automobile traffic in the early 1900s, Los Angeles grew as people sought its many job opportunities and fair weather. In no time, the fledgling city began a romance with the automobile. By the 1920s, cars had become cheaper and filled southern California’s early roads, putting the streetcars out of business and severely cutting into the railroads’ profits. But, traffic congestion soon threatened to choke off the city’s development, and urban developers began to build roads. Route 66 was commissioned in 1926 into this mix, which fit right with Los Angeles’ plans. Little did they know how fast their city would grow, demanding hundreds of new roads and highways to accommodate the thousands flooding to the Golden State. Over the years, the metropolitan area’s piece of Route 66 would change dozens of times.

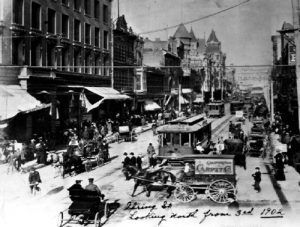

The original 1926 route followed Colorado Boulevard from Pasadena to Fair Oaks Avenue, Huntington Drive, Mission Road, and North Broadway to 7th Street (US 101), where Route 66 officially ended. The heart of the city, at 7th and Broadway Streets, was a bustling place then and even more so today. Still, the area provides much 1920s and ’30s architecture, including movie theatres, cafes, and business buildings that speak of an earlier time.

Called the Historic Core of the city, the area had its heyday from the late 1890s to the early 1930s. Like the rest of the nation, it eventually deteriorated, and many buildings were abandoned as people moved to the suburbs. However, with the help of several preservation groups over the last 25 years, “old downtown Los Angeles” has been rediscovered. Several historic buildings are being restored and converted into loft apartments, business buildings, galleries, restaurants, and boutiques. This colorful district boasts North America’s largest unbroken string of pre-1931 buildings today.

The area is often called the Broadway Theatre and Shopping District because of the many art deco movie palaces and stores that line the busiest street in Los Angeles. Broadway had the world’s largest display of neon signs at one time. Though that is no longer true, several movie theatres and office buildings are undergoing restoration and conversions, and the neon signs are making a big comeback. While you’re here, check out a few of these historic places: The Los Angeles Theater at 615 S. Broadway is the last and most extravagant of the ornate movie palaces built on Broadway in downtown Los Angeles between 1911 and 1931. The Orpheum Theatre also continues to entertain the public at 842 S. Broadway. Look for the vintage neon signs of the Roxie between 5th and 6th Streets, the Rialto at Broadway and 8th, United Artists on 9th Street, the Palace Theatre at 630 South Broadway, and numerous others.

While in this area, you won’t want to miss the Grand Central Market at 317 South Broadway, which has offered Los Angeleans fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, poultry, and fish since 1917. Check out several market restaurants or head down to Cole’s P.E (Pacific Electric) Buffet at 118 East 6th Street, the oldest continuously operated Restaurant and Bar in the City of Los Angeles. Another choice might very well be Clifton’s Brookdale Cafeteria at 648 South. Broadway has been doing brisk business with Route 66 travelers and locals since 1928.

In the meantime, Los Angeles was still building highways, especially as the 1930s dust bowl hit the Midwest. Thousands of Dust Bowl refugees, who had lost their farms or jobs, began to flock to California. By 1934, the drought was the worst in U.S. history, covering 75% of the country and severely affecting 27 states. In 1936 alone, some 70,000 refugees flooded Los Angeles, prompting the City Police Chief to implement the Bum Blockade, which dispatched 136 LAPD officers to control the borders of Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon to keep out “undesirables.”

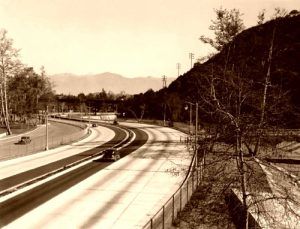

In 1936, Route 66 was re-commissioned to extend to Santa Monica, and Los Angeles was still building roads to keep up with the influx of its new residents. By December 1940, the city dedicated the Arroyo Seco Parkway, which became the new alignment of Route 66 from Pasadena to Los Angeles and the first “freeway” in the United States. Later it became known as the Pasadena Freeway and Highway 110. In 2002, however, it was designated as a National Scenic Byway, and its name officially changed to the Arroyo Seco Historic Parkway.

Today, the parkway has some beautiful scenery and is the quickest route from Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles. Still, travelers beware—it also has more wrecks than any other freeway in the city. It was initially designed for slower speeds with plenty of curves to enjoy the scenery. The curves and short entrance and exit ramps can often cause back-ups and wrecks on the highway. Avoid peak commuter hours in the morning and late afternoon for maximum enjoyment.

The parkway begins off Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena. The Fair Oaks off-ramp leads directly into downtown South Pasadena, providing several quaint shops and restaurants and an opportunity to see the 1915-era Fair Oaks Pharmacy and the 1925 Rialto Theatre. The parkway continues, providing beautiful views of the San Gabriel Mountains before winding through a chain of small parks and craftsman-era bungalows in the Highland Park neighborhood.

You’ll soon pass through a historic stretch with several potential stops to downtown Los Angeles, including the Southwest Museum, the Lummis House, the Audobon Nature Center at Debs Park, Heritage Square, and the Los Angeles River Center and Gardens. As you near downtown, other interesting side trips are to Dodger Stadium, Union Station, Elysian Park, Chinatown, and the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historic Monument.

Continue on to downtown Los Angeles to see the many historic buildings in the city center. To continue your Route 66 journey, return to the parkway and exit at Sunset Boulevard to move on through West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Santa Monica.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2024.

See our Los Angeles Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

The Bum Blockade – Stopping the Invasion of Depression Refugees