“Down there by the river is a man… and he bears the look of an animal and sees things no animal should ever see. He has been driven beyond all towns and all systems… Though it is long past too far, he keeps going.”

— Ricki Lee Jones

By Jesse Wolf Hardin

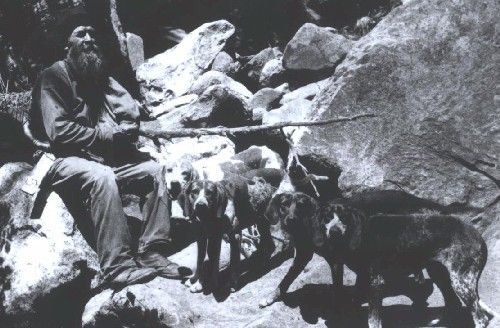

The cascading notes of Ol’ Lilly’s hunting horn were some of the signature sounds by which he was known, as peculiar to the man as the recognizable songs of his mixed-breed dogs. It could be said that throughout his life, he was a man more relaxed and intimate with wild places and his faithful, panting canines than with any friend or wife.

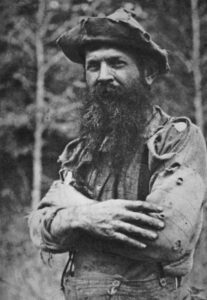

Benjamin Lilly was one of the greatest hunters and most fascinating characters of the quickly civilizing West. He dressed like a mountain man, preferred sleeping outdoors to a proffered room and bed, and would sometimes walk hundreds of miles in pursuit of a single elusive bear. From childhood hunts in the 1870s until he died in the latter part of the 1930s, Mr. Lilly was what we’d now call an “anachronism:” a man still inhabiting an earlier time– and in many ways, the last of his kind. Ben was an unrepentant atavist, a proud throwback, and a devout adherent to archaic ways of being that he believed to be more meaningful and heroic. Or at least more tolerable… and more vitally experienced!

Ben was known far and wide for his incredible stamina when walking or running. He carried only the barest essentials in his surplus pack, with no more bedding than a wool blanket and a tattered canvas tarp. When he philosophized that “Property is a handicap to man,” he wasn’t proposing some socialist manifesto, but rather, a recipe for camping light! Long before beatniks, hippies, and punks, Ben Lilly preached the importance of owning little so that our things don’t own us. He preferred liberty and free time over possessions he couldn’t carry on his back, and eschewed anything that required constant maintenance and thus a sedentary life.

Lilly was a latter-day Daniel Boone in his canvas pants, brogans, and a coonskin cap, packing a Winchester 1886 or 1894 rifle and a huge handmade knife. Like Boone before him, he endlessly sought out new vistas and challenges, in an attempt to escape the population density and social propriety that his relentless hunting of lions and bears had actually helped make possible. He lives on as a larger-than-life legend among the rural folk of Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona… and particularly among the individualistic residents of the Gila National Forest, where he hunted throughout the latter half of his life. Only recently have the last folks who could remember meeting Lilly died, and their children and grandchildren continue to be the keepers and tellers of his timeless tale.

As he himself tells it in Frank Dobie’s The Legend of Ben Lilly, “My reputation is bigger than I am. It is like a shadow when I stand in front of the sun in late evening.”

He was not merely blowing his horn but hearing and heeding a call.

It’s said that some people are born “marching to a different drummer,” leading them in a different direction than the vast majority of their civilized kind. They may be legendary heroines or salty folk heroes, long-forgotten heretics, or anonymous hermits ensconced in their howling caves. And even Jesus needed forty days and forty nights in the wilderness– away from the prattle and preconception of village life– in order to fully experience the truth of self and the reality of God.

A few such fringe-dwellers have managed to earn the accolades or acknowledgment of their society through some combination of ability, fortune, and circumstance: Intemperate military officers, whose disobedience of official orders somehow results in their army’s victory, in what turns out to be a pivotal fight. Women with besmirched reputations and incorrigible attitudes who prove their mettle during a siege by “Red Leg” guerrillas or a frontier cholera outbreak. Individuals who are just warming up when others are already running from the heat. Courageous leaders and founders of significant social, religious, and artistic movements, who started as the kinds of kids that not even the strictest schoolmarm could make sit still. They are often the last to give up the olden ways, and also the first to try something strange and new. They may laugh or cry a little more freely than others do– or else stubbornly cling to silence, and tightly cleave to solitude.

Their fevered allegiance to a calling or a way of being has always come at a cost, be it a misunderstanding, oppression, or neglect. Among Native American tribes, such personalities were highly valued as soothsayers, healers, teachers, and agents of Spirit during moments of crisis… but the remainder of the time their wild-eyed intensity could be just a little too much for their brethren, resulting in medicine men and shamans usually setting up their lodges at the extreme outer edges of any village or camp.

It is known that Crazy Horse did not like having his picture taken; however, this sketch, made in 1934 by a Mormon Missionary while interviewing one of Crazy Horse’s family members, is said to be accurate. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Buddha would have died unknown and been viewed as crazy while he lived if no one had taken the time to really listen to him. Joan of Arc may have been an “emissary of the Lord” and bore his ring, but she avoided the fire only so long as she served the interests of the church, state, and king. Sioux warrior Crazy Horse was honored for his brilliance and excess during that tribe’s frequent battles, but few people wanted to sit and have tea with him in the peaceful weeks or months between. The pundits, partygoers, and power brokers of Washington, D.C., found famed Indian fighter Davy Crockett entertaining– but also crude, odoriferous, and overbearing. And oddly enough, the issue that put an end to the famed Indian fighter’s career as a U.S. Congressman was daring to object to President Andrew Jackson’s policy of forcibly removing Indian tribes from the land of the ancestors who lived, loved, and died before them.

Ben Lilly was just such a man, neither noble nor licentious but authentic to a fault. He was in some ways closer kin to the lions and bears that he hunted than the settled country folk who adored him or the government men who eventually paid his wage. Like those other furry beasts of the forests and deserts, it could be said that the always-bearded Ben Lilly was cut from a wilder cloth.

Ol’ Ben’s fervent and archaic form of Christianity did not exclude drawing spiritually from the natural world: “I always sleep better [on the earth],” he tells us. “Something agreeable to my system seeps into it from the ground.”

The early Greeks would have called this “something agreeable,” the “anima mundi:” the palpable energies of the planet itself, and the native spirit of place. For Lilly, it was simply an unfathomable incarnation or creation of an obviously outdoor-loving God.

Truly, the land was as a bodily extension of Ben’s being… even if he seemed sometimes to treat his other affiliated parts– his fellow creatures– coldly or harshly. At the same time that he was making his living by killing, the hyperawareness of the hunt brought him deeper into awareness and celebration of all life. He understood how blue jays and tree squirrels functioned as aids and agents of his own physical senses, alerting him to the movements of both people and game. He learned to hear through the ears each region’s animal sentinels and to see through the eyes of its watchful birds. The fields, hills, and hollers were more than pretty scenery or an opportunity for outdoor recreation– more than a stage for the acting out of an individual’s personal dramas. Lilly viewed nature as an unfolding lesson, as a book that any man could read and understand if he only took the time to pay attention. And as a sermon and solution. As the challenge and the reward.

“Every man and woman ought to get out and be with the elements a while every day…” Ben advised. The outdoors would alert, instruct, and inspire us. Reawaken our intuition and instinct, and stir our emotions. Reconnect us to the basic elements of life like hunger and food, weather, and fire. Strengthen our intent. Temper our steel.

If anything, Lilly followed his own advice to the extreme: seldom stepping indoors except to buy a few supplies or share a grateful rancher’s meal. Mabel Hudson of the old Hudson Ranch near here told about her parents spotting him, nestling among his dogs in a roadside ditch one day, and how they offered him a place to stay. “Thank you, but I prefer to spend the night right here if that’s okay.”

Perhaps as a result of so much time outside, Ben was physically impressive and a man of extreme determination. By the time he was a young man, he was already amazing the locals with his unexcelled stamina, and he’d often perform feats of strength for their entertainment. One such demonstration was to pick up a giant anvil by the throat with a single hand. Dobie reports one occasion when he was abnormally tired and unable to make the lift, but he kept straining and trying until blood literally “burst out of his fingertips.”

Old-time Catron County cowboy Lee Sturgeon passed down a story from his childhood when one day he and some other boys spotted Ben carrying a hunter client on his back across a swollen river. “Get off that old man!” they shouted. The client yelled back that he sincerely wanted to, but simply couldn’t. Lilly had him in an iron grip, and he wasn’t about to let go!

And apparently, he could be bluntly honest. One story making its way around various Catron hunting camps tells of a young boy asking Lilly if it was true that his dogs “never run deer.” Bear and lion dogs are trained to chase nothing else and not to get distracted by the scent or sight of other game. Needless to say, most proud hunters and dog handlers would see the little fellow’s question as an opportunity to brag, exaggerate, obfuscate or lie. But not Benjamin Lilly. “I’ll tell you, son,” the by-then old man replied… “sometimes they run them ragged!”

Big Thicket in Texas.

Ben may have been a perpetual wanderer, but he was never truly lost. If anything, it was in the thickets and brambles that he was fairly found and claimed. He always traveled with a sense of destination– if only the direction of his baying dogs or the way the last bear went. While his trail twisted and turned like a meandering river, he was, in many ways, making a beeline away from the settlements, the crowds, the niceties, and the responsibilities of domestic life. And likewise, he was always aiming for a place. A place of refuge… and hopefully, of redemption.

Whether out of love or lust, personal loneliness, or accepted convention, Benjamin Lilly tried marriage twice. But what person’s feast is another’s poison. What fits some men like a glove is, to others, a straitjacket of habit, chore, and constraint.

It seems that for Lilly, “tying the knot” meant being tightly secured with a rope, trussed up like a hog. It meant having a fellow’s movements restricted, his natural tendencies and urges subdued, and his options limited.

Ben wed his first wife, Lelia, in Louisiana in the 1880s, a woman he came to call a “daughter of Gomorrah.” She complained, among other things, that the chores never got done… and that she needed his attention. But married or not, he continued to take his cues from the scent on the wind and any tracks found nearby, from the noisy admonitions of migrating waterfowl and the unsated hunger of his soul. He would take off at the drop of a hat, accompanied by a pack of 20 or more dogs. The “call of the wild” beckoned him away, the forest sirens’ irresistible songs.

According to Dobie, one day, his wife asked him to go out and shoot a troublesome chicken hawk. A year later, he showed up, and his wife naturally wanted to know what could have happened to him. “That hawk kept a-flyin’,” was all he supposedly said. Long afterward, Mrs. Acklin, proprietor of the general store in San Lorenzo, remembers Lilly doing his best to remain unaffected after receiving a letter from one of his grown kids. “Mother died last week,” it said in part. “She set a place at the table for you every meal” for what had been some 16 years.

As we point out again and again in this book, what made the close of the 19th Century and the start of the 20th so interesting were the heightened contrasts, the dramatic twists, the confrontations between the extremes of aesthetics and tastes, values, and beliefs. Between urban and rural interests, the incredibly rich and the fundamentally poor. And like the age he matured in, Benjamin Lilly was a man of contradictions. He loved the attention of children, playing with any little boys he met and calling them “podnah,” and yet he left his sons to raise themselves essentially. Father was usually gone, either somewhere down an unused trail or else passing through nearby towns, amassing a cadre of young fans. While they were adjusting to having no one except their mother to talk to or ask questions of, Ben would be out somewhere telling exciting stories of the great hunt to their neighbors’ wide-eyed children.

Like everything else about him, Lilly’s contradictions were substantial and profound. He was righteous enough never to work or hunt on Sundays, yet he was capable of neglecting his family… and abandoning his wife when she needed him most. “Why can’t we just live in harmony?” she reportedly asked one morning as they sat at the deathbed of their young son, Dick. Ben responded that there was nothing left between them, then walked out the door for the last time. It was said that Lelia was a little crazy already when he met her, but his years away– and his leaving her at such a traumatic time– were no doubt a significant factor in her later spending some thirty years under wraps in an institution for the mentally insane.

Lilly remarried in 1890 to a woman named Mary. As in his first relationship, when it came to allocating attention and time, family came in a distant second. It seemed he preferred the attention and flattery of strangers to the comforts of loved ones and home, and that he preferred the solitude of the chase above all. Eleven years later, he had moved off again, taking his dogs with him, but never going back for his wife and three kids. It wasn’t that he was incapable of loyalty, but his loyalty was to the freedom of an unfettered life, with neither rules nor rent. His ultimate fealty was to the rugged canyon and wide-open spaces, to the baying of hounds and a trail perfumed with mountain lion scent.

Similarly, he was a profligate slayer of birds and beasts, and yet in some ways respected nature and its denizens as much as anyone. It is said that “man always kills that which he loves.” While John Muir was helping protect wild landscapes like Yellowstone and Yosemite, Benjamin Lilly was making his life in the wilds: a life chasing bears. For thousands of years, our species has filled both the roles of predator and prey. This was an ancient imperative… maintaining intimacy with the natural world by risking life and drawing blood.

Lilly usually wore a giant knife on his belt, where it was easiest to grab– the favored harpoon of a graying landlocked Ahab. A product of the passion-soaked South, he joined James Bowie in often preferring a blade over a gun. A favorite way of dispatching a bear on the ground was to get in close and strike deep with the big knife. That way, he didn’t have to worry about hitting his dogs with an errant bullet, as they run circles around the raging bruin… and it gave him the opportunity to make things personal.

He fashioned large numbers of “Lilly knives” over the years using any old tool steel he could find, and he was known for giving the smaller ones away as gifts to the many hospitable folks he met on his trips. He forged a special dirk for bear —a massive “Arkansas Toothpick” tempered in panther oil, featuring a blade with an exaggerated S-curve similar to an Asiatic Kris. He believed its wavy shape contributed to bleeding, and, being fully sharpened on both sides, he could not only stick it deep into his quarry but also cut in either direction.

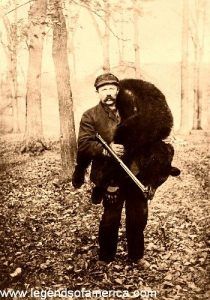

Bear hunter in the wilds of the American West.

Lilly was, nonetheless, a rifleman tried and true. Near as I’ve been able to determine, he had no use for either pistols or shotguns. He even used a rifle for taking ducks, carefully shooting their heads off so as not to destroy any meat. He likely carried percussion arms into the woods when he was growing up, and any cartridge gun he could afford as an adult. Sometime around the turn of the century, he began carrying a 30-30 for light game, variously reported as a Winchester or Marlin lever action, and he’s been photographed holding a Savage 1899… but for a long time, his preferred caliber for bear was .33 WCF, chambered in the notable Model 1886. There are stories around these parts about a rifle Ben supposedly left behind in a cave, and then was never able to find again. What a treasure that would be to find, even hopelessly rusted shut– not only an artifact of a man’s life but a piece of a legend.

Lilly may or may not have been the pretty incredible marksman that he and others claimed he was, but it’s reasonable to accept his simple assertion: “I never saw a lion that I did not kill or wound.” As a child, little Ben perfected his shooting skills not on paper bulls-eyes but on moving targets like buzzards and bats, darting bees and sweet-singing cedar waxwings. On the creatures he and dogs would eat, and on the predator species he felt a holy duty to eliminate. To the contemporary reader, Lilly’s enthusiasm for the kill will no doubt appear insensitive and unnecessary at times… and admittedly, he once confessed to killing eleven deer in a short stretch and leaving them lie. While he feasted on a wide variety of game, apparently, the alligators he shot, he never bothered to dress or cook.

Perhaps he thought he was already more emotionally armored and detached than he liked, without ingesting the energy of these scaly denizens of the Louisiana bayous. Like both the American Indians who preceded him and his own ancient Celtic ancestors, Lilly believed that “you are what you eat:” that consuming the flesh of a particular animal imparts to the eater not only essential nutrients but also some of its qualities and traits. He thus believed that dining on domestic cattle would dim his senses and slow his pace, whereas suppleness and energy could be expected from any wild meat. Of these, there was none he loved more than grilled lion steak, which he felt contributed to both his intrinsic hunter’s instincts and catlike strengths. More than once, Ben Lilly affectionately cared for lion cubs he’d orphaned, raising them as pets, and then killing and eating them when they grew up. If he was conflicted, it didn’t show.

There is a time for us to wander,

when time is young and so are we.

The woods are greener over yonder,

the path is new, the world is free.

So do your roamin’ in the Springtime,

and find your love in the Summer sun,

the frost will come and bring the harvest,

and you can sleep when the day is done.

Time is like a river flowin’,

with no regrets as it moves on,

around each bend a shinin mornin’,

and all the friends we thought were gone.

— From I Know What It Means To Be Lonesome, by The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

Lilly was feral, meaning he’d reverted to his “original wild state.” A dog is considered feral when it abandons the security of human ownership to respond to its nagging inner instincts —the impulse to run free under a full moon —and to secure its own food, adventure, and rewards. Ben wasn’t “transformed” into this cage-shunning man of the woods, but rather, his days and nights on the hunt reinforced and affirmed his native wildness. From a young age, Lilly liked to make animal sounds to announce his presence or play tricks on reticent ladies or distracted little kids. Tales abound of Ben’s childlike enthusiasm– swinging through the trees like a monkey, chattering like a squirrel. It’s said that on one occasion, he challenged a prideful runner to a race, then beat him to the finish line by running like an animal on all fours. He even walked flat-footed rather than heel-first… “like a bear,” he said.

There comes a time when such a man finally looks back, only to be confronted by his wilder tracks.

A heavy presence pads through the forest primeval, heavy like nightfall, heavy like the weighty body of the universe. We feel its approach, even as we swim the glare of the midday sun—its corporeal mass, slowly moving towards us, intent on enveloping us. It is the spirit of a giant that survived the Ice Ages, now tearing apart the fallen trunks of ancient trees, knocking flailing salmon and furry golden marmots high into the air, continuing to stalk the darkly hidden caves of our dreams: the grizzly bear!

The sound of their name is enough to pass a charge, like electricity, through our bones— enough to cast a long and deep shadow across our rapidly shrinking arrogance, illusory sense of omnipotence, and fragile certainty. One glance at a grizzly’s unmistakable claw marks eight feet up the side of his scratching tree, and every nerve comes instantly to attention. Every sense is alerted, every light turned on at once in the mortal housing of the soul. Enlivened! Every cell is open-eyed and open-mouthed, every molecule on tiptoes, straining to perceive.

Awakeness. Intensified perception. These are the first gifts of the great bear. With their slow lumbering thunder comes the excitement and clarity of lightning bolts: sudden, penetrating, en-lightening! Truly, one perceives more in grizzly country. Our senses honed to a fine, irreconcilable edge.

Without ever actually seeing a bear, the mere thought of it is like a claw stripping the opaque film from our perceptual lens. The civilized traits of inattention and indifference are swiftly gutted like fish and left to curl and dry on hot river rocks. Sloth joins nonchalance, pawed into a carrion pile beneath a layer of sticks and dirt.

“Anyone can kill a deer,” the great bear killer Lilly tells us. But “it takes a man to kill a varmint.” By that, he didn’t mean shooting coyotes or so-called pest species the way people do now when they write articles about “varmint hunting.” Ben was talking about nothing less than personally facing at very intimate ranges a critter that’s bigger, meaner, and potentially better than we are! Ben himself served as proof that our species was a good deal stouter, more resilient, and aware when they had to match wits and lungs with an animal capable of making us his lunch. Humans evolved specialized brain cells and improved response times thanks to being hunted for thousands of years by predators far larger than us. Eyes trained by bone-crunching necessity to discern the slightest movement along an aspen-lined trail evolved the capacity to recognize patterns and create art. Ears alert to the sound of approaching bruin footsteps were well suited to the development of language and to notice every nuance of a deftly picked bluegrass song. Similarly, noses, no longer needed for basic survival, eventually lose their capacity to smell—to discern the nature and proximity of threats and to enjoy this world of subtle and not-so-subtle scents thoroughly. And with the decrease in both adventure and danger, civilized humanity may be becoming increasingly oblivious, less and less vitally aware.

“He showed far more feeling for several of the individual lions he’d killed than for any human being he mentioned,” writer Frank Hibben wrote of Ben after several days trying to keep up with the aging hunter. Most of the people he knew “never took their place.” He knew this and more. He could see inside of both animals and men, he said…. could “see beneath their skin.”

Lilly belonged to a wilder tribe, the clan of the furry, the scaled, and the feathered. “A man has to be accepted into the family,” as Lilly often said. “You can’t live with them and you can’t hunt them if you aren’t a member.” Even as he slew the beasts, he sensed that he was one of them… and that it was them that he belonged.

Since the very beginnings of humankind, we have honored Ursus, and the earliest evidence of religious or ritual activity is the bear skulls stacked like an altar in the caves of Southern Europe. In addition, hundreds of primitive terra-cotta “bear nurses” have been excavated from various Neolithic sites. Most are enthroned female bears or women wearing bear masks, and most are nursing a cub. They likely represent the Mother of All Animals, and mythologically, the cub becomes Zeus on the bear’s nipple, Zalmoxis and Dionysus, Artemis and Diana, the huntress.

Our ancestors in both the “Old” and “New World” watched the bear go into its den every winter and emerge every Spring — an obvious herald of rebirth, the return of life to a hungry land and hungry people. The people of urbanizing Europe harnessed the bear and its mythology to the purposes of the field and plow. In England, they had the “strawbear,” while in Germany he was called the Fastnachtshar: a man dressed in a bear costume made of straw who would be led in early Spring to each house in the village. There, the man-bear would dance with all the women. It was believed that the more enthusiastically they danced, the richer the coming crop would be. Pieces of the straw costume would be playfully snatched by the young women and placed either beneath their pillows to ensure fertility, or else in the nests of their chickens to encourage the laying of needed eggs. The bear has long reminded humankind of a crucial lesson: how out of suffering and separation comes a chance for unity and bliss… and out of the icy sleep of winter comes the regeneration of life.

Benjamin Lilly was briefly the Chief Huntsman for a party that included another admirer of outdoor life, Theodore Roosevelt, who was entertained by stories of the hunt and demonstrations of his physical prowess. In President Roosevelt’s journal of the trip, he described Ben as “equaling Cooper’s Deerslayer in woodcraft, in hardihood, in simplicity– and also in loquacity.” Lilly must have been out of sorts among all the attending dignitaries and reporters, for he wasn’t able to get Roosevelt a bear, and his subsequent firing no doubt hurt his well-earned pride. But if so, he likely never showed it. As Roosevelt writes, he “never met any other man so indifferent to fatigue and hardship”… and no doubt, to the needs, whims, and judgments of others.

Lilly began shooting and preparing specimens for the Washington-based Biological Survey in 1904. Over the coming years, the National Museum received numerous mounted specimens for its collection. These include the bear, deer, otter, and, interestingly enough, the now-extinct Mexican Gray Wolf, and the endangered ivory-billed woodpecker.

It was in New Mexico, at age fifty-five, that Lilly began getting paid for what had heretofore been his pleasure. And his obsession. His hunting prowess convinced area ranchers to pool their money into a bounty fund especially for him, representing ranches from the Animas in the southern Bootheel of the state, north to Quemado, and West to Show-Low, Arizona. The Federal government began paying bounties in 1914 on bears that were “proven cattle killers,” but Lilly found that private funders were much less particular. They reasoned that so long as there was a single grizzly left, the calves they depended on for their livelihood would remain in danger, and not a single porch dog would be safe. The scarcity of forage in the Southwest made raising cattle a tricky enough business as it was, and depredations by wolves, lions, and bears seemed to force the area’s ranchers into a war of extermination in self-defense.

The river where Lilly had some of his greatest hunting success — the very river I live on — is paradoxically called the San Francisco… and is named after St. Francis, protector and patron Saint of wildlife.

Needless to say, neither the hungry bears nor the cows they coveted were the only ones in danger, and sometimes the hunter could end up the hunted. It was in 1913 on the Blue River in Arizona, just thirty miles West of my land, that Lilly had what he considered the closest call he ever had. Thrice wounded at long range, a vengeful grizzly waited in ambush in a patch of dense undergrowth. Ben was waist-deep in snow and only a short fifteen feet away when the frothy bruin charged. Swinging his rifle quickly to his shoulder, he managed to slow the animal’s advance with a shot to the breast, then put another round into its gigantic head. Anger and momentum propelled the beast forward, the last few feet, and into Lilly’s heaving chest. The old man then brought the matter to a conclusion by thrusting his big knife into the bruin’s still-beating heart.

Over the years, Lilly occasionally trapped for the Biological Survey as well as the U. S. Forest Service… but a company job with requirements, schedules, and restrictions fit him about as well as a size ten collar on a size fourteen neck! His supervisors and handlers never fully understood his motivations. After all, he wasn’t just another bankrupted cowboy looking to make a buck, or a wayward husband avoiding entanglement or litigation back home. “You are condemned, you black devil,” Lilly once shouted, before piercing a bear with his knife tied to a pole. “I kill you in the name of the law!” Ben was passionately committed to what he believed to be a God-sent mission, a holy war of sorts against bears and lions: the equivalent of the barbarian hordes of the Bible, threatening the security and industry of the human race.

On the wall of the 3-Trees Guns Shop in Reserve, visitors can see the mounted head of what is considered to be the last grizzly killed in this state, in the Summer of 1915. She was taken a short way from here by Bailey Hulsey using a Winchester 1886 .40-65, in what we usually call Bishop Canyon. While not the biggest of specimens, she still looms large in the imagination. She was– like Lilly himself– the last of her kind. Glass eyes blazing, mouth open in a permanent snarl, she represents for New Mexicans an end to competition from a breed of creature we’ve been violently contending with since the earliest prehistoric battles for a habitable cave.

Bergen Riddle is one of my backwoods neighbors, living as he does a mere ten miles over the hill (as the crow flies). To this day if he hunts his hounds at all he does so on foot, the old way. He’s quick to point out how many bears and lions an outfitter with a pack can take out of the woods annually, driving his dogs down dirt logging roads on the platform of his truck until they cut scent where one of the key predators had crossed the road.

Then all they have to do is release the pack, pay attention to the signals from the dogs’ radio collars, and then drive as close as possible to where their quarry ends up treed. In comparison, Lilly’s record of 98 bears killed in a single year is notable, if not exactly restrained. One has to take into account that the aging huntsman walked his hounds on their hunt for scent, and then walked or ran to catch up with them once they were off and baying on a hot track.

Like the gunfighter John Wesley Hardin, Ben Lilly was a man of distinction and contradiction in a time of compliance and change. When he took refuge in solitude and wildness, it was not only from society’s hypocrisy and oppression but from his own deep personal ambivalence and unresolved issues.

Some hundred and fifty years earlier, Daniel Boone suffered a constant itch to move on. As quickly as he’d help settle a new region, subdue the native Indians, and make it safe for settlers, he’d start complaining of having no “elbow room” and soon head West again. The “mountain men” trappers of the 1830s through the 1850s were often hired by government surveyors and engineers for the railroads, inadvertently inviting in the very crowds and domestic lifestyles that they’d left Albany or St. Louis to avoid. Another, less free way of living hounded Lilly’s tracks even as he was hot on the trail of bears and visions.

Had Lilly been asked to define himself in a single word, it would no doubt have been “hunter.” He hunted for lion and bear, for food and for fun. He hunted for personal resolution and reconciliation, for untamed places and a sense of purpose as well as peace.

It was still relatively early in the 20th Century when a sensitive young man with an artist’s soul, Everett Ruess, disappeared forever on one of his many burro treks out West. His body was never found, leaving us unclear if his death was accidental or a homicide… or if he simply took off with no intention of coming back. Unlike with Ruess, few tears were shed when old Ben Lilly passed away in bed. I’m sure he would have rather perished on a hunt, exhausted beyond measure in a Herculean effort to keep up with the pack. Or he might have preferred to have the tables suddenly turned, and find himself the feast, filling the belly and the heart of some great warrior of a beast.

Towards the end of his life, he spent considerable time at the G.O.S. Ranch, but by 1931, he was largely incapable of focus, let alone of hunting. He whiled away his final days on Mary Hines’s “county farm” on Big Dry Creek, forty miles south of here, near the still small town of Pleasanton. Benjamin Lilly passed away on December 17, 1936, telling Ms. Hines, “I believe I’ll stay in bed today.” There is undoubtedly something ironic about the man who hated sleeping indoors spending his last hours between the sheets… that one who courted and encountered so many mortal threats should die with his “boots off” instead. We’re reminded of volatile gunslinger Doc Holiday’s final words as he lay in the Glenwood Springs Sanitarium bed, staring at his stockinged feet: “Well, ain’t that funny!”

And even less funny than that was what they did to old Ben’s body.

Frank Dobie quotes Lilly: “I never saw a man with his face shaved clean until I was a big boy. When I saw him, I thought he was a dead man… walking about, and I was mighty scared.” He, therefore, grew up determined “never to scare anybody into thinking I was a corpse.” No one ever saw him without his trademark facial hair, as long and unkempt as any creature’s fur. “Ever since I could grow a beard, I have had one.”

Elk grazing before the mountains by Kathy Alexander.

That is, until a witless Silver City undertaker shaved it off.

In some ways, we can see the great huntsman was fortunate to die when he did — before witnessing a Southwest stripped of much of its wildness… its people weakened by a paucity of challenge, restricted by thousands of laws and regulations, stunted by their reliance on public services, and disempowered by dependence on food purchased from stores.

Lilly was destined to speak the language of the “Cains of the animal world” and to join them in a shared way of being as well as a fateful contest. Ultimately, it is not someone’s accidents and illnesses that kill them, but surely as his heart rips and tears. In the end, the man who may have killed more lions, blacks, and grizzlies than anyone else in his time didn’t want to live in a world without bears.

Sometimes when I stop writing long enough to step outside, I can hear not only the songs of wind and river but the screams of wildly mating lions, and the bugling of amorous elk. From the compost of Fall come the anxious births of Spring, followed by the sounds of tiny paws and feet on well-worn trails. And creating an aural bridge between the dark and the light– death and life– are the beckoning notes of old man Lilly’s hunting horn.

©Jesse L. “Wolf” Hardin, 2006, updated November 2025.

About the Author: Jesse L. “Wolf” Hardin is the author of the popular book Old Guns & Whispering Ghosts, which includes several fascinating stories of the colorful characters and firearms of the wild West, as well as dozens of previously unpublished historical photos. Hardin is a lifelong student of Western history and antique firearms, a prolific artist, an entertaining Old West presenter, and a storyteller. In addition to Old Guns & Whispering Ghosts, he has published four other books and numerous articles in more than 100 magazines. Hardin, who lives in an isolated canyon in the Gila Mountains of southwest New Mexico, also tends to a wildlife sanctuary.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West