In 1842 the real march on Oregon began. This year, the imperialists, led by Senator Thomas H. Benton of Missouri, had succeeded in having an official trail-exploration expedition sent as far west as the Wind River Valley in present-day Wyoming, led by Benton’s new son-in-law, John C. Fremont. Fremont’s report, issued early in 1843, roused broad enthusiasm. In 1843 he again went out and spent most of the two following years exploring foreign land in Oregon and the Mexican possessions in what is now the United States. His reports of these expeditions became the chief guidebook of later emigrants.

At the time Fremont was making his first trip, a party of about a hundred started for Oregon under Dr. Elijah White, a member of the Willamette Valley Mission. Previously White had quarreled with Jason Lee and left the area, but when he returned, he boasted the title of “Indian subagent for Oregon.” Dr. McLoughlin s agent at Fort Hall sent a guide to lead them to the Willamette Valley. This party did not pass Fort Vancouver, but McLoughlin later helped many of its members by extending credit at the company commissary to them. In the following year, nearly half the members of the White party moved on to California; however, their arrival had stimulated the Americans in the Willamette Valley to form a loose civil government for themselves. The British subjects in the valley first joined the movement but withdrew when they discovered the nationalistic character of the activities.

In 1842, Dr. Elijah White brought orders to Dr. Marcus Whitman that part of his missions was to be closed because the board was tired of the dissension among the workers and disappointed in the number of conversions. Whitman and his colleagues were determined to disregard the instructions. In the fall of this year, Whitman suddenly decided to rush east, regardless of the weather. After a quick trip across the mountains, he went straight to Washington to urge his ideas on Government officials, asking for forts to protect emigrants along the Oregon Trail. He then visited New York, where he met Horace Greeley and filled him with enthusiasm for the disputed territory. Finally, he went to Boston to consult with his board. Almost immediately, he started west again, lecturing as he went, to join the travelers at Independence and turn them toward Oregon.

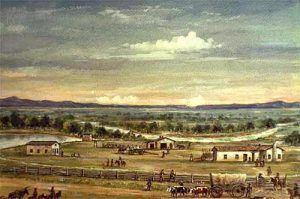

In the meantime, nearly a thousand people were assembling at Independence, Missouri, and preparing to start west. In November and December of 1843, about 875 persons straggled into Oregon. Like those who preceded them, they were assisted in various ways by the Hudson’s Bay Chief Factor of the Columbia, Dr. John McLoughlin.

The following year, the settlers reorganized and strengthened their provisional government and welcomed 1,400 more arrivals. Still, Dr. McLoughlin extended credit to the straitened newcomers, who promised repayment in wheat and other commodities to be produced on the new lands. He may have hoped to redeem himself in the eyes of his superiors by making Fort Vancouver the export center for the territory.

In 1845, which saw the arrival of more than 3,000 immigrants, the provisional government was fully established. In the same year, the Hudson’s Bay Company forced the resignation of Dr. John McLoughlin. After winding up his affairs, he moved south to regain the land he had laid claim to 15 years before and expected some repayment from the many newcomers he had helped. Many settlers had not paid their debts to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and McLoughlin’s later years were embittered because he had to use his life savings to reimburse the company. Though he soon became a citizen of the United States, his land claim was not recognized until five years after his death.

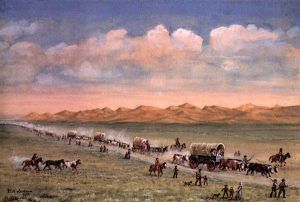

The acquisition of vast western lands swelled the migration to all parts of the West. By 1848 the Oregon Trail was deeply rutted. The discovery of gold in California in that year drove it deeper into the prairies, for it carried the great bulk of the gold seekers at least to a point west of South Pass, Wyoming.

Though much sympathy was given to the western-bound emigrants, few asked for it. They were taking part in one of the great mass movements of history, and they knew it, as is shown by the diaries they kept under difficult conditions, by the letters they wrote to the hometown newspapers and friends, and by the efforts they made to leave their names on various rocks along the way. To many, the journey was an exhilarating picnic, with gossip, chatter, love-making, sightseeing, and adventure providing them with something to boast about for the rest of their lives. If the hardships were greater than they anticipated, the majority was undismayed. Cholera epidemics along the trail in 1849, 1850, and 1852 took a heavy toll, as epidemics did in cities.

On the whole, the emigrants had such good health on the trail that hordes of sick and anemic persons journeyed to the Missouri River to travel at least for a time with the parties. Had the emigrants stayed at home, the average annual death rate would have been 500 in every 20,000; probably, the death rate on the trail from natural causes was lower than at home. Most deaths not resulting from epidemics were the result of rashness or carelessness. Loaded guns in the hands of amateur frontiersmen were a leading cause of accidents.

Every party had some members who were sure they could find shorter and better routes than experienced guides; the tragic experience of the Donner party took place because the members acted on advice in a letter written by a man whom they had never heard.

As Army posts were opened along the way, the officers became increasingly annoyed by the foolhardiness of the travelers. Finally, to save themselves the labor of rushing about rescuing the foolish, they forcibly organized the trains under military rules and passed them along under escort.

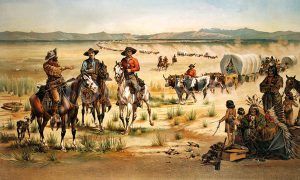

While many emigrants feared the Indians and were always alert, others could not be made to take reasonable precautions against surprise. The Indians stole when they could and caused occasional deaths during raids. Still, they were not serious menaces until the 1860s when they realized that the invaders were driving away and killing off the buffalo and other animals on which the natives depended for food and clothing. By this time, the Indians had become thoroughly disillusioned with any hopes that the whites would keep the land treaties. The whites took the best lands through these agreements and gave the Indians the worst. In addition, comparatively little of the promised compensations in money and goods ever reached the natives. Even the Army officers sent to quell uprisings when the Indians became desperate reported, with a stern sense of justice, that the Indians had just cause for their frantic last stands. For many years the forces sent against the Indians were inadequate, but when at length, the Government undertook to finish the job of expropriation, the results were swift and final.

Great hardship was caused by the settlers’ determination to carry their prized possessions. Many a cherished chest and spinet on the West Coast was carried overland at the price of semistarvation.

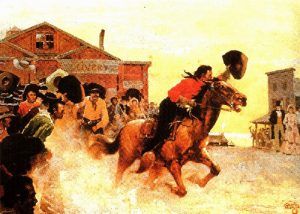

By 1850 the immigrants were beginning to clamor for quick mail service and better transportation, but it was 1859 before an overland stage went as far west as Colorado. The Pony Express, which gave California the first fast mail service, was inaugurated in 1860. Though it lasted only 16 months and ruined its promoters, it provided the country with one of the most exciting series of relay races in history. In 1861 a telegraph line connected the Pacific Coast with the East.

After much talk about building a railroad to the far west, the Federal government accepted the responsibility. A Congressional act permitted the Central Pacific to build eastward from Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific to build westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa, until their lines should meet, with a bait of princely land grants to stimulate rivalry between the two companies for distance covered. The most formidable engineering difficulties were encountered at the western end. Still, the building of the Union Pacific was a far more dramatic enterprise as it was carried through at a time when many of the Indian tribes of the plains were actively and fiercely hostile. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory, Utah, a golden spike was driven into a cross-tie of California laurel, celebrating the junction of the rails pushed from the East and the West and the completion of an iron span across the continent.

Wagons continued to follow the Oregon Trail until late in the 1880s, but the days of pioneer travel were over, and the physical frontier was almost gone. Many who went west remained only a short time, then turned back to settle in the Middle West or to resettle in their native states east of the Mississippi River. Few immigrants found the quick wealth and happiness they had sought. Through the years, the migrations grew steadily smaller.

Excerpted from The Oregon Trail, the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean; compiled and written by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, 1939.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See:

Danger and Hardship on the Oregon Trail

Disease and Death on the Overland Trails