The Zuni people, like other Pueblo Indians, are believed to be the descendants of the Ancient Puebloans who lived in the desert Southwest of New Mexico, Arizona, Southern Colorado, and Utah for a thousand years. Today the Zuni Pueblo, some 35 miles south of Gallup, New Mexico has a population of about 6,000. Archeological evidence shows they have lived in this location for about 1,300 years.

Their tribal name is A’shiwi (Shi’wi), meaning “the flesh.” The name “Zuni” was a Spanish adaptation of a word of unknown meaning. The Zuni speak their own unique language which is unrelated to the languages of the other Pueblo peoples and continue to practice their traditional shamanistic religion with its regular ceremonies, dances, and mythology.

In 1540, the first Spanish explorers led by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado encountered the Zuni Indians living in six or seven large pueblos along the banks of the Zuni River, of which, all are in ruins today. These villages, called Hawikuh were located next to fertile ground where the Zuni could take advantage of abundant water resources. The Zuni had a successful and well-established agricultural economy.

The Spaniards, who were searching for the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, were disappointed to find only the dusty, crowded Zuni village. On the verge of starvation, Coronado asked the Pueblo leaders for food for his army. They refused. Rather than perish, Coronado ordered an attack on Hawikuh in order to save his troops. After a brief skirmish resulting in several Zuni deaths, Coronado and his men took possession of the pueblo, which then became his headquarters for several months.

The arrival of the Spaniards explorers disrupted the Zuni’s trading patterns, land use, and settlement system, as well as introducing new diseases which took a devastating toll among their population. However, the Spaniards also introduced domestic livestock and new crops, including wheat and peaches.

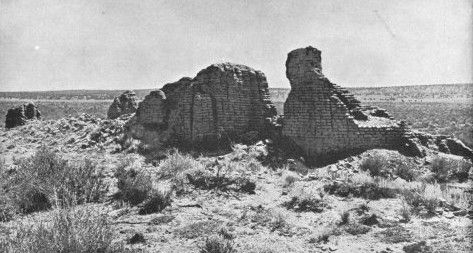

Spanish missionary efforts began at Hawikuh in 1629 when Fray Estevan de Perea traveled to the major Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi pueblos to begin Catholic teachings. That same year the Spanish established and constructed Mission La Purísima Concepción at Hawikuh. Religious and cultural tensions grew within the pueblo and peaked a few years later when the Zuni killed the resident priest, Fray Francisco Letrado. The Zuni, fearing retaliation from the Spanish, hid in the mountains and did not return to Hawikuh until three years later.

Reestablished by the late 1650s, the mission at Hawikuh suffered frequent Apache raids from the south. One, in 1672, resulted in the death of another priest and the burning of the mission. During this time, there was a decline in the Zuni population and subsequently, in the number of occupied villages. The attrition was the result of political pressure from the Spaniards and raiding from the Navajo and Apache. Violence soon became a regular part of the otherwise peaceful Zuni as they defended their land and resources from encroachment from other groups and resisted Spanish attempts to suppress their culture and religion. The Zuni joined with other pueblos in August of 1680 in the historic Pueblo Revolt which succeeded in driving the Spaniards out of New Mexico. During the rebellion, the Zuni destroyed Mission La Purísima Concepción. The former Zuni community at Hawikuh and Spanish mission are now in ruins, but continue to be visited and protected as a Zuni ancestral site.

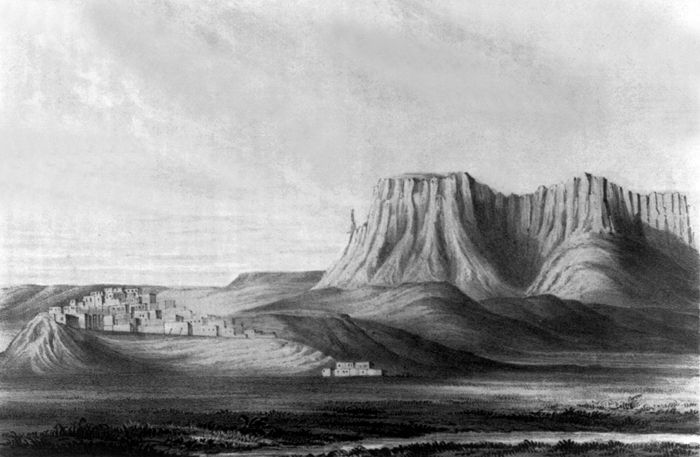

Afterward, the Zuni fled to the top of the Dowa Yalanne mesa and prepared for defense. Between 1680 and 1692 the Zuni built and maintained a large settlement that incorporated many pueblo rooms on the mesa top, an area of less than 617 acres. Since it did not contain enough land to support the entire Zuni population, the Zuni continued to farm and graze livestock in the valleys below.

Dowa Yalanne was pivotal in the development of Zuni settlement patterns as it was the first village in which the whole Zuni population gathered into a single settlement. Although it is unlikely that the other villages were totally abandoned, apparently every Zuni family maintained a residence atop the Dowa Yalanne that could be used for refuge when the Spaniards returned. The mesa top was also a position defensible against the hostile attacks of the Apache.

In 1692, Diego de Varga, the Spanish general in charge of the “reconquest,” entered the village peacefully, made amends, and convinced the Zuni to relinquish the occupation of Dowa Yalanne. Rather than return to their former scattered pueblos, the entire tribe settled at Halonawa on the north bank of the Zuni River. Following this event, Halonawa became known as the Zuni Pueblo.

The Franciscans returned, and the church was rebuilt and Mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe was built in 1705. Continued Navajo and Apache raiding led to the establishment of sheep camps which were utilized as refuge sites. Situated along ridges and on the benches throughout the Zuni River Valley, these safe areas were difficult to access, having many hidden corrals and small rooms. Other refuge sites were established at the base of mesas for agricultural purposes.

In 1848 the Americans asserted their authority over the Mexican Southwest, and in 1877 federal officials created the Zuni Reservation. The Southern Pacific Railroad reached nearby Gallup, New Mexico in 1881, signaling a new era of non-Indian expansion and settlement. Missionaries accompanied the newcomers including Mormons who settled east of the village in the Zuni mountains in 1876 and Presbyterians a year later. Traders also arrived, encouraging the Zuni to raise sheep and cattle for shipment east and a new cash-based economy began.

Mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe began to be revived when priests were reassigned to the pueblo. It was re-roofed in 1905, but more significant alterations took place in the 1960s. In a three-way partnership between the Zuni Tribe, the National Park Service, and the Catholic Diocese of Gallup, the mission and convento were excavated from 1966-1967, and reconstruction of the church began in 1969.

Today, Zuni are distinct in that they have managed to remain quite unaffected by outer influences. They still claim the same land they always lived on, an area about the size of Rhode Island. They also mainly reside in one city — Zuni, New Mexico.

Although there are Zuni Indians who live outside of the city and the general area, they are few and far between. The tribe has managed to remain intact due to the fact that they did not get involved in problems, conflicts, or wars that didn’t concern their own people. Remaining autonomous, they were relatively unaffected by the changes around them.

Zuni life, much like it was in the past, is still deeply religious and very different from that of other tribes. The Zuni gods are believed to reside in the lakes of Arizona and New Mexico. The chiefs and the shamans carry out ceremonies during religious festivals. Song and dance accompany masked performances by the chiefs while the shamans pray to the gods for favors ranging from fertile soil to abundant amounts of rain. The shamans play an important role in the community as they are looked upon for guidance as well as knowledge and healing.

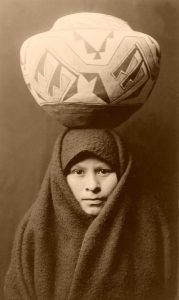

The Zuni Reservation is isolated from the outside world which allows the people to go about their existence relatively unencumbered by modern western civilization. They still live a peaceful, deeply religious existence and speak their own language. The reliance on corn as a mainstay of their economy has been replaced, however, by the tourist trade in pottery and jewelry.

The Zuni Pueblo is the largest of the 19 New Mexico pueblos, with more than 700 square miles and a population of over 10,000. It also features the Hawikuh ruins, abandoned during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, as well as craftsmen shops, and multiple events throughout the year. Zuñi Pueblo is on the Zuni Indian Reservation, two miles north of Zuni, New Mexico, on NM 53.

Visitors are welcome daily from dawn to dusk and tours are offered for a fee. Photography is allowed by permission only.

More Information:

Pueblo of Zuni

1203B NM Highway 53

PO Box 339

Zuni, New Mexico 87327

505-782-7000.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated February 2021.

Also See:

Ancient & Modern Pueblos – Oldest Cities in the U.S.