The oldest permanent seacoast fortification in the continental United States, Castillo de San Marcos, in St. Augustine, Florida, was built between 1672 and 1756.

After nine wooden forts failed to adequately protect Saint Augustine and the Florida coast, the Spanish Crown authorized the construction of a stone star-shaped fort, surrounding moat, and earthworks. The northernmost outpost of the Spanish Caribbean, its focus was to protect the shipping routes along the Florida coast and defend the Spanish territories from British aggressors, with whom they were fighting for regional supremacy during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Though the Spanish founded St. Augustine in 1565, it would be another hundred years before they began building the Castillo de San Marcos. The earlier wooden forts did not last long. Some of them burned down, storms washed some away, and some just rotted from neglect.

However, two events took place around the mid-1600s that made the Spanish realize that it was time to build a stronger fort to defend their town and colony of La Florida.

The first event was in 1668 when the pirate Robert Searles attacked St. Augustine. Unlike Sir Francis Drake, who had attacked and burned St. Augustine to the ground a hundred years earlier, Searles did not burn the town or destroy the wooden fort. However, the Spanish feared he might return with more men and turn the town into a pirate camp to attack Spanish treasure ships. They needed more protection.

The second event was the founding of South Carolina by the English in 1670. The English had settled in Jamestown, Virginia, 42 years after the Spanish founded St. Augustine, followed by the Pilgrims’ settlement at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620. But, these colonies were too far away to be a threat. Even the establishment of Maryland and New York over the following decades did not have much effect on the Spanish. However, that changed in 1670 with the establishment of South Carolina. The English were too close for comfort, and the Spanish Crown sent money to St. Augustine to build a stone fortress.

The star-shaped design of the fort originated in Italy in the 15th century. The “bastion system,” named for the projecting diamond or angle-shaped formations added onto the fort walls, was the most commonly and effectively used of the significant architectural variations. Skilled workmen and masons were recruited in Cuba. These men gathered a force of workers from Cuban convicts and nearby Timucua, Guale, and Apalachee Indians to build the fort. On October 2, 1672, the ground was broken for the building of the fortress, and the work began. Instead of wood, this new fort was built of coquina, a stone found near the coast on Anastasia Island. This limestone formed over thousands of years from the shells of the tiny coquina clam cemented together through time and nature into a solid but soft stone.

Some workers used pickaxes and crowbars to hack the shell rock out of the ground. Others gathered oyster shells from the many Indian shell middens in the area. These shells were burned into lime, which, when mixed with sand and water, became the mortar to cement separate coquina blocks.

Slowly, the walls rose. Since no one had ever built a fort out of coquina before, they had no idea how strong it would be. At least they knew it would not burn or get eaten by termites, but how long would a fort made of seashells hold up under cannon fire? No one knew, so they built the walls 12 feet thick, with the walls facing the harbor 19 feet thick!

Given its light and porous nature, coquina would seem to be a poor building material for a fort. However, the Spanish had few other options; it was the only stone available on the northeast coast of La Florida. However, coquina’s porosity turned out to have an unexpected benefit. Because of its conglomerate mixture, coquina contains millions of microscopic air pockets, making it compressible.

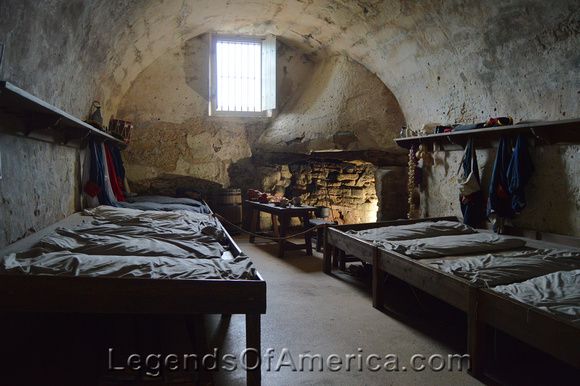

In August 1695, the Castillo de San Marcos, including curtain walls, bastions, living quarters, a moat, ravelin, and seawall, were completed.

Only seven years after the new fort was finished, James Moore and his British forces from South Carolina attacked St. Augustine in 1702. Moore captured the town and set his cannon up among the houses to fire at the fortress. For 50 days, the British besieged the fort, but a strange thing happened. Instead of shattering, the coquina stone absorbed the shock of the hit! The cannonball just bounced off or stuck in a few inches. The shell rock worked! A cannonball fired at more solid material, such as granite or brick, would shatter the wall into flying shards, but cannonballs fired at the walls of the Castillo burrowed their way into the rock and stuck there, much like a bee would if fired into Styrofoam. So, the thick coquina walls absorbed or deflected projectiles rather than yielding to them, providing a surprisingly long-lived fortress.

The English burned the town before they left, but the Castillo emerged unscathed, making it a symbolic link between the old Augustine of 1565 and the new city that rose from the ashes. To strengthen the defenses, The Spanish erected new earthwork lines on the north and west sides of St. Augustine, thus making it a walled city.

In 1738, the Spanish Governor Manual de Montiano at St. Augustine granted freedom to runaway British slaves and encouraged slaves to escape for sanctuary in Florida. If the fugitives converted to Catholicism and swore allegiance to the king of Spain, they were given freedom, arms, and supplies. As more and more slaves took advantage of the offer, the first legally recognized free community of ex-slaves was established. Known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or Fort Mose, it was located north of St. Augustine to serve as another defense.

In 1740, the Matanzas Inlet was still unfortified when General James Oglethorpe’s British troops from Fort Frederica in Georgia attacked St Augustine. Again the Castillo was besieged and Matanzas Inlet blockaded. But, the Spanish did not waver during the 27-day British bombardment. The attack also taught the Spanish the strategic value of the Matanzas Inlet and the need for a strong outpost there. Consequently, in 1742, they completed the Fort Matanzas Coquina Tower to block any Southern approach to St. Augustine.

From 1756-52, Fort Mose was rebuilt in masonry, and earthworks were extended to complete a northernmost defense.

In 1763, as an outcome of the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War), Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain in return for La Habana, Cuba. The British garrisoned Matanzas and strengthened the Castillo, holding the two forts through the American Revolution. The Treaty of Paris of 1763, which ended the war, returned Florida to Spain.

Spain held Florida again until 1821, when serious Spanish-American tensions led to its cession to the United States. The Americans renamed the Castillo Fort Marion in 1825, and during the Seminole War of 1835-42, it was used to house Indian prisoners. Confederate troops occupied it briefly during the Civil War, and Indians captured in Western military campaigns were held there later on. It was last used as a military prison during the Spanish-American War.

In 1924, Fort Marion and Fort Matanzas were proclaimed national monuments. In 1942, the original name, Castillo de San Marcos, was restored. Today, the National Park Service administers them. They are located at 1 Castillo Drive in downtown St. Augustine.

See our St. Augustine Photo Gallery HERE

More Information:

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

1 South Castillo Drive

St. Augustine, Florida 32084

904-829-6506

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Fort Matanzas – Protecting St. Augustine

St. Augustine – Oldest U.S. City

Source: National Park Service