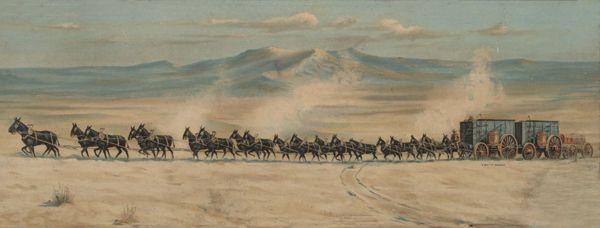

20-Mule Team hauling Borax in Death Valley

Borax was first produced commercially in the United States in California at Clear Lake north of San Francisco, from about 1864 to 1868. At that place, the industry flourished until the early 1870s when borax began to turn up in large and purer quantities in several of the alkaline marshes of eastern California and western Nevada — notably around Columbus and Teel’s Marsh. Large deposits were located in the Saline Valley flats northwest of Death Valley as early as 1874, prompting many borax claims up through the 1890s. However, the discoveries underwent only limited development because of the lack of railroad facilities, the extremely harsh climatic conditions, and the basic fact that they were not rich enough to make their exploitation economically viable. In 1874 minor production began in earnest at Searles Lake in San Bernardino County, California west of the Slate Range, where construction and operation of a refinery ultimately turned the valley into one of the most extensively worked and most productive borax areas of the region. Neighboring deposits were subsequently found in marshes near Resting Spring southeast of Death Valley and on the salt pan north of the mouth of Furnace Creek.

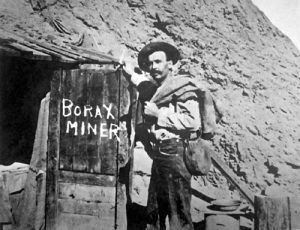

The discovery of borax north of the mouth of Furnace Creek was made in 1881 by Aaron and Rose Winters. William T. Coleman and Company immediately bought their holdings for $20,000. He subsequently formed the Greenland Salt and Borax Mining Company (later the Harmony Borax Mining Company), which in 1882 began operating the Harmony Borax Works, a small settlement of adobe and stone buildings plus a refinery. The homestead, later known as the Furnace Creek Ranch, immediately to the south was intended as the supply point for his men and stock. The Amargosa Borax Works in the vicinity of Resting Spring and a Coleman enterprise was run during the summer months when the extreme heat adversely affected the refining process in the valley. A small-scale borax operation, the Eagle Borax Works, was started by a French man named Isadore Daunet in 1881 and was located further down in the valley near Bennett’s Well. It lasted only until 1884, when the inefficiency of its operation combined with personal setbacks resulted in Daunet’s suicide. It is frankly astonishing that any of these works experienced half the success they did, for their distance from main transportation systems and the daily hardships involved in working under uncomfortable desert conditions were severe obstacles to their economic success.

The type of borate being exploited on the salt flats of Death Valley was ulexite, in the form of “cotton balls” that were scraped off the salt pan and then refined by evaporation and crystallization. It was initially believed that this was the only form of naturally occurring borax that was commercially profitable. Continuing exploration in the area by Coleman Company prospectors and others soon confirmed that the playa borates that were presently being worked were a secondary deposit resulting from the leaching of beds of borate lime. The primary deposit, a richer form of borate later named in honor of William T. Coleman, occurred in beds and veins similar to quartz-mining operations. In 1883 three men by Philander Lee, Harry Spiller, and Billy Yount stumbled upon a large mountain of such ore south of Furnace Creek Wash in the foothills of the Black Mountains.

Selling Monte Blanco to Coleman, reportedly for $4,000, they left, having made their fortune off the borax industry. An even larger deposit east of the Greenwater Range and about seven miles southwest of Death Valley Junction was also found within a year. It was beginning to appear that this was the southernmost lode in a rich colemanite belt stretching northwest to southeast along Furnace Creek Wash to the area of Furnace Creek Ranch. Coleman also bought this property, naming it the Lila C.

These discoveries that were soon to revolutionize the borax industry in the United States seemed destined for the moment to lie untouched, for several reasons: first, these larger and more concentrated deposits required underground mining methods; second, more sophisticated techniques were necessary for their refinement as they were not readily soluble in hot water; third, no transportation lines extended into this undeveloped area; fourth, no nearby supply center existed; fifth, this badlands region was so hot in summer that it precluded mining activity during that season; and last and perhaps most important, Coleman’s desert refineries were doing so well that he seemed justified in continuing their operations for a while yet.

These extensive and pure deposits would probably have remained undeveloped if not for the discovery in 1883 of more colemanite ledges in the Calico Mountains 12 northeast of the railroad at Daggett in San Bernardino County. Because of their proximity to the railroad, these deposits posed a serious threat to Coleman’s Death Valley business. Immediately buying up the most important lodes, he decided to look to the future and initiated research at his Alameda, California refinery to determine a profitable method of refining this material. Meanwhile, his Harmony and Amargosa works continued production.

With the dissolution of Coleman’s financial empire in 1890, Francis Marion “Borax” Smith took possession of his holdings at Borate, in the Death and Amargosa Valleys, and his Alameda refinery, and consolidated these and other miscellaneous properties into the Pacific Coast Borax Company. In addition, he took over the colemanite deposits in the Furnace Creek Wash area. Declining borax prices due to borax imports from Italy and a consequent glut of the product on the market prompted Smith to close down his Death Valley holdings and concentrate on operations at Borate, where less expensive processes could refine richer ore. These became the first major underground borate workings in the United States, and during the years 1890 to 1907 Borate became the chief producer of borax and boracic acid in the country. In time, however, the workings had been carried to such a depth that the cost of their further development was prohibitive, causing Smith’s attention to turn once more to his Death Valley reserves.

Hindering development of the Lila C Mine was its isolation, but, fortunately, profits from the Calico operation were sufficient to subsidize the construction of the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, projected to stretch from Ludlow on the Santa Fe line to Death Valley Junction and on to Goldfield, Nevada. Work at the mine started even before the railroad was finished, the initial ore recovered being transported to market via 20-mule teams, once more pressed into service. The T & T Railroad began in May 1905 and reached Death Valley Junction by 1907. A seven-mile-long spur was immediately laid, reaching the Lila C camp of Ryan Station. Borate was abandoned, and all its equipment was moved to the new area where a calcining plant was also installed. The Pacific Coast Borax Company had not forgotten its holdings further west near Death Valley; however, as evidenced by a newspaper report in 1909, due to the low price of borax, the Lila C might have to be abandoned in favor of the more cheaply-mined deposits of Mount Blanco that existed in inexhaustible quantities. Such a move was possible with the construction of a narrow-gauge railroad from Ryan to the deposits. As the ore at the Lila C began to play out about 1914, plans were already underway to shift operations to reserves further west on the edge of Death Valley. Company engineers had determined that those large deposits would keep the company going for years, while more was always available on the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew claims.

A new railroad was needed to open up these deposits, resulting in the construction of the Death Valley Narrow-gauge Railroad operating from Death Valley Junction to the newly-opened mines. In January 1915, the Lila C was closed, though not wholly abandoned, and the borax activity shifted to the new town of Devair, almost immediately renamed (New) Ryan, on the western edge of the Greenwater Range overlooking Death Valley. A new calcining plant was built at Death Valley Junction to handle the lower-grade ores from the Played Out and Biddy McCarty Mines. According to the original Death Valley Railroad survey (New), Ryan was only the temporary terminus for a line, eventually extending down Furnace Creek Wash to the Corkscrew Canyon and Monte Blanco deposits as needed. However, this projected extension never materialized because the Ryan mines — the Played Out, Upper and Lower Biddy, Grand View, Lizzie V. Oakley, and Widow — proved even more productive as development increased until 1928. At that time, a deposit of easily accessible rasorite, more economical to mine due to its proximity to its new processing plant, was discovered near Kramer (later Boron), California, again precipitating a shift in mining operations. When the Death Valley Junction concentrating plant shut down in 1928, a significant era in borax production and processing in the Death Valley region ended. From then until 1956, borate mining all but ceased, with mines being kept on a standby basis and furnishing only small tonnages to fill special orders. This lull continued until Tenneco, Inc., started open-pit operations at the Boraxo Mine near Ryan in 1971. Borax mining continues in the area today.

Borax has a wide variety of uses. It is a component of many detergents, cosmetics, enamel glazes, insecticides, fire retardants, and more.

The main Death Valley Park Visitor Center and Museum at Furnace Creek provides additional information about borax mining in Death Valley, and park rangers are on hand to answer questions.

Additionally, a privately-owned Borax Museum is located in the Furnace Creek Ranch in the oldest building in Death Valley. Initially, the building served as an office, a bunkhouse, and the ore-checking station for the Borax miners. Initially located in Twenty Mule Team Canyon, the building was moved to Furnace Creek. The museum exhibits a mineral collection and the history of Borax in Death Valley. Behind the museum building is an assembly of mining and transportation equipment.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Characters of Early Death Valley

Desert Steamers in Death Valley

Primary Source: Death Valley National Park