Avilla, Missouri, seems to be the “Capitol” of this ghost town section of Route 66 and is still called home to about 125 souls.

Situated in an affluent farming district, the area was settled in the 1830s and 1840s, especially along the many winding streams in the area. The first schoolhouse was built in the 1840s, about 1.5 miles southeast of present-day Avilla. The dirt-floor log cabin was called the White Oak School as it was located near White Oak Creek.

The town of Avilla was founded in 1856 and platted, and six blocks were laid out around a public square in July 1858 by Andrew L. Love and David S. Holman. Mr. Love was the first Justice of the Peace, and Mr. Holman was the first merchant and postmaster establishing the post office in 1860. The settlement was named for Avilla, Indiana.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Avilla was called home to about 100 people. Like many other Missouri settlements, its residents were initially split over Missouri secession, and some were slave owners. However, the town leaders and most residents were loyal to the Union cause and newly elected President Abraham Lincoln.

Dr. Jaquillian M. Stemmons, an early settler, town leader, and staunch Union man, organized a company of local men and neighbors in Avilla to protect their own homes from roaming bands bushwhackers. Though Stemmons owned slaves, he had inherited them and kept them for their safety during the Civil War. The town militia, known as the “Avilla Home Guard,” was one of the first and consisted predominantly of older men citizens. Most of the younger men were leaving to join regular military forces.

Avilla’s political alignment was in sharp contrast to neighboring Sarcoxie to the south, where the first regional Confederate flag was raised. The rebel “Stars & Bars” also flew over nearby Carthage, just ten miles to the west, following an early Confederate victory at the Battle of Carthage on July 5, 1861. In early 1862, Stemmons and the Home Guard were tipped off that area secessionists planned an attack on Avilla, and General James G. Blunt at Fort Scott, Kansas pledged reinforcements. However, before the Kansas soldiers arrived, a group of over 100 pro-Confederate guerrillas, thought to have been led by “Bloody Bill” Anderson, attacked northeast of Avilla on the evening of March 8, 1862. Their main target was Dr. Stemmons’ home. At that time, a number of the militiamen were having a meeting in Stemmons’ house when the guerillas surrounded the two-story log building. The Confederate assault was met with heavy gunfire. However, the rebels continued the attack and managed to light the log building on fire. Before it was over, Dr. J.M. Stemmons and another militiaman, Lathan Duncan, were killed. Several others were shot and burned, and two were taken as prisoners. The rest of the heavily out-numbered militia withdrew and re-formed near the north edge of Avilla and braced for another onslaught, but it did not occur.

Though the rebel attack on the Stemmons home was intended to terrorize and intimidate the loyal Unionists in Avilla, it had the opposite effect. Those who died or were injured fighting off the guerilla attack were seen as heroes, and the town’s militia began to not only boldly resist but also go on the offense. Everyone in the town took up arms as the Union flag continued to fly in the town center park, guarded by the townsmen. Schoolhouses were closed, and many families evacuated their women and small children to safer areas in other states.

Though the Union Army gained possession of Missouri in 1862, the area around Avilla remained plagued with bushwhackers and occasional small bands of Confederate regulars or guerrilla raiders. The Avilla Home Guard, augmented by a few Union soldiers of the US Cavalry, extended its patrols within eastern Jasper and western Lawrence Counties to protect the town and countryside in several local skirmishes. During this time, many bushwhackers were tracked down and shot, and within a short time, the rest of them grew to fear the deadly Avilla “pioneer marksmen.” After a rebel skeleton with a bullet hole in the skull was found just south of town, it was hung from the “Death Tree” in Avilla, where it remained for over a year as a warning to other bushwhackers.

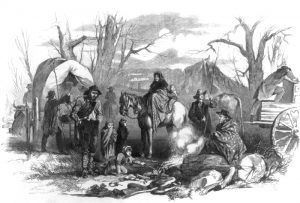

By 1863, a Union Army garrison was encamped in Avilla under the command of Major Morgan. Tents were erected, and storehouses, barns, and homes were converted to temporary Army barracks and headquarters, which housed hundreds of soldiers at various times and several refugees. The town became known to the Missouri Militiamen informally as “Camp Avilla.” The garrison maintained a formidable and effective defense throughout the rest of the war and became a sanctuary for refugees of nearby burned-out towns such as Carthage.

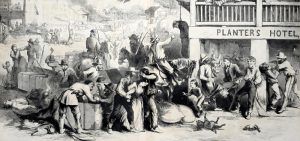

When the war was finally over in 1865, Avilla became an overnight boomtown during the Reconstruction Era. As much of Jasper County lay in ruins, merchandise and construction materials were hauled by wagon train from Sedalia, Missouri, the closest railroad shipping point to Avilla. From here, supplies were made available to area communities, and even farmers from Kansas traveled to Avilla for seed, building supplies, and provisions.

Captain Thomas Jefferson Stemmons, a Union commander, and son of the late Dr. J.M. Stemmons returned home to Avilla. They started a mercantile with partner D. B. Rives, the first new business established after the Civil War. A hotel called The Avilla House was erected in 1868, and by the next decade, the town boasted two general stores, two grocery stores, a doctor’s office, a “notion” (sewing) store, two boot & shoe stores, livery & feed stable, three churches, and a drug store.

A new school was also built in the 1880s that served grades 1-12. At that time, the population had increased to about 500 people. However, when the railroad came through the area, it was not built through Avilla, so its growth was stunted.

Over the years, Avilla’s population declined. Decades later, the Old Carthage Road through Avilla was paved and became Route 66 in 1926. The town sported about 165 people by this time, a hardware store and lumber yard, a barbershop, beauty salon, a bank, a cafe, and several gasoline stations and garages.

In May 1932, the town made the news when the Bank of Avilla was robbed. by members of the notorious “Irish O’Malley Gang,” which also resulted in the kidnapping of the cashier, Ivy E. Russell. The group comprised typical Depression-era outlaws who had merged with another group of thugs known as the “Ozark Mountain Boys.” After the successful robbery at gunpoint, the men made off with Ivy and drove to nearby Carthage, where they pushed him out of the car and left him by the roadside. After several other bank and store robberies and murders throughout the Midwest, all of the members of the O’Malley Gang were either captured or killed. One of the criminals was sentenced to a 75-year prison term for the Avilla bank robbery.

In the meantime, Ivy E. Russell continued to operate the Bank of Avilla until it closed its doors in 1944. Today, the old bank building continues to stand and is utilized as the post office.

After World War II, Avilla continued to lose population as people moved to larger cities for employment opportunities. However, a larger school building was established, and many of the previous smaller schools were consolidated to form the elementary/middle school Avilla R-13 School District, which still operates today. Afterward, the high school students were bussed to other nearby towns.

In the 1960s, US Route 66 was bypassed with I-44, and many of the remaining businesses failed or were relocated by the 1970s. In 1971 a large fire broke out at the Avilla lumberyard, which destroyed several buildings, including most lumber companies, the Boy Scout Meeting Hall, and some private residences. The lumberyard was later rebuilt, but by the late 1970s, deteriorating town shops had been sold, resold, and finally deserted.

Today, Avilla has settled down to a quiet way of life and is supported mainly by area farmers.

Route 66 continues westward to Carthage for 12 miles, allegedly passing through two old townsites – Forrest Mills and Maxville, but there appear to be no remains of these places.

Just before Carthage is an opportunity to visit Red Oak II, a “ghost town” built from numerous area buildings, some of which once stood on Route 66. To get to Red Oak II, follow Missouri Highway 96/Route 66 west for 7.9 miles to County Road 120, one mile north to Kafir Road, and turn left (west) for .3 miles to the site.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Ghost Town Stretch Beyond Springfield, Missouri

Missouri Route 66 Photo Gallery

Sources:

Missouri Department of Natural Resources

Missouri Historical Society

Wikipedia