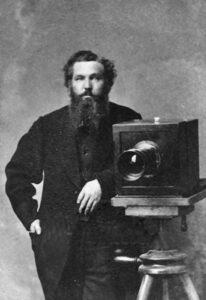

Alexander Gardner was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the Civil War, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and the conspirators and execution of the participants in the Lincoln assassination plot.

Alexander Gardner was born in Paisley, Scotland, to James and Jane Glen Gardner on October 17, 1821. He and his family later moved to Glasco. Raised in poverty, he became an apprentice jeweler at 14 and worked for seven years. He also took evening classes at the Glasgow Athenaeum to further his education, studying astronomy, optics, physics, and chemistry. At 21, he joined the Glasgow Sentinel as a reporter.

Raised in the Church of Scotland, he was influenced by the work of Robert Owen, a Welsh socialist and father of the cooperative movement. In 1850, he and his brother James traveled to the United States to establish a cooperative community near Monona, Iowa. However, Gardner never lived there, choosing to return to Scotland to raise more money. At that time, his photography flourished in Paisley, and his expertise in the wet-plate process soon gained him recognition. He also published pamphlets promoting emigration to the United States colony called Clydesdale in the wilderness of Iowa. He persuaded many friends and relatives to settle in this semi-socialist “Utopia.”

He became the owner and editor of the Glasgow Sentinel in 1851 and quickly turned it into the second-largest newspaper in the city. Visiting The Great Exhibition in 1851 in Hyde Park, London, he saw the photography of American Mathew Brady, which sparked his interest in the field. Shortly afterward, he began reviewing exhibitions of photographs in the Glasgow Sentinel and experimenting with photography independently. At some point, he married Margaret Sinclair, and the couple had two children.

In the spring of 1856, Gardner and his family immigrated to the United States. He took his mother, wife, Margaret Gardner, and their two children with him. When he arrived at the Clydesdale colony in Iowa, he discovered that several members were suffering from tuberculosis. His sister, Jessie Sinclair, had died from the disease, and her husband was soon to follow. He then returned with his family to the east, settling in New York.

Gardner contacted Mathew Brady and became his assistant and a portrait photographer that year. Gardner specialized in making large photographic prints called Imperial photographs. These life-size, hand-tinted portraits were eagerly sought by the rich and famous. As Brady’s eyesight began to fail, Gardner assumed increasing responsibilities in Brady’s studio in Washington, D.C. In 1858, Brady put Gardner in charge of his Washington, D.C. gallery and was joined by his brother James.

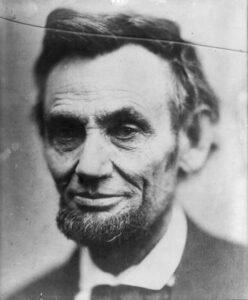

Abraham Lincoln became the President of the United States in the November 1860 election, and along with his election came the threat of the Civil War. Gardner was well-positioned in Washington, D.C., to document the pre-war events. With the start of the war in 1861, the demand for portrait photography increased as soldiers on their way to the front posed for images to leave behind for their loved ones. Gardner became one of the top photographers in this field.

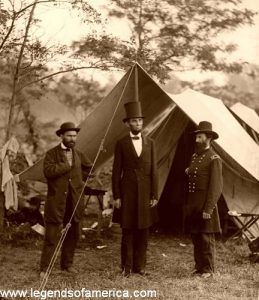

Allan Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand, 1862. Photo by Alexander Gardner.

In July 1861, Matthew Brady and Alfred Waud, an artist working for Harper’s Weekly, traveled to the front line and witnessed the Battle of Manassas, Virginia, the war’s first major battle. The battle was a disaster for the Union Army, and Brady came close to being captured by Confederates. Afterward, Brady decided to make a record of the war using photographs. Mathew Brady shared his idea about photographing the Civil War with Gardner and soon dispatched over 20 photographers, including Gardner, to record the images of the conflict. Each man was equipped with a traveling darkroom to process the photographs on-site. As well as making battlefield images, Gardner also took photographs of troops and notables in the field. Frequently, Brady sold his images and those of his other photographers to illustrate newsweeklies.

Gardner’s relationship with Allan Pinkerton, chief of the intelligence operation that would become the Secret Service was central to promoting Brady’s idea to President Lincoln. Pinkerton recommended Gardner for the position of chief photographer under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Topographical Engineers. Following that short appointment, Gardner became a staff photographer under General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. At this point, Gardner’s management of Brady’s gallery ended. The honorary rank of captain was bestowed upon Gardner in November 1861.

This put him in an excellent position to photograph the aftermath of America’s bloodiest day, the Battle of Antietam. On September 19, 1862, two days after the battle, Gardner became the first of Brady’s photographers to take images of the dead on the field. Over 70 of his photographs were displayed at Brady’s New York gallery. In reviewing the exhibit, the New York Times stated that Brady could “bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it…” Unfortunately, Gardner’s name was not mentioned in the review.

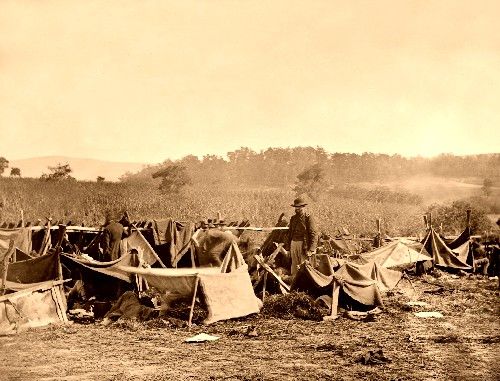

Caring for the wounded at Antietam, 1862, photo by Alexander Gardner.

Gardner’s work has often been misattributed to Brady, and despite his considerable output, historians have tended to give Gardner less than full recognition for his documentation of the Civil War. When Lincoln relieved McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, Gardner’s role as chief army photographer was reduced. That winter, Gardner followed General Ambrose Burnside, photographing the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862. Next, he followed General Joseph Hooker.

In early 1863, when Brady refused to give Gardner public credit for his work, Gardner ended his working relationship with Matthew Brady. He and his brother James opened their studio at 7th and D Streets in Washington, D.C., hiring many of Brady’s former staff. He also continued to photograph the hostilities on his own. Organizing his corps of photographers, he led them to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to photograph the aftermath of that battle. He was briefly detained by Confederate forces on July 5, 1863, when he crossed their path at Emmitsburg, Maryland. He also led his group to the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia, from June 1864 to April 1865. All of his photographers received full credit for their work. Talented and vigorous cameraman Timothy O’Sullivan became head of his photographic corps while he remained in Washington through most of the last months of the war.

He also took what is considered to be the last photograph of President Abraham Lincoln just five days before his assassination on April 15, 1865. He documented Lincoln’s funeral and photographed the conspirators involved with John Wilkes Booth in Lincoln’s assassination. Gardner was the only photographer allowed at their execution by hanging, photographs of which would later be translated into woodcuts for publication in Harper’s Weekly magazine.

After the war, Brady established a gallery for Gardner in Washington, D.C., and Gardner was commissioned to photograph Native Americans who came to Washington. D.C. to discuss treaties.

When Matthew Brady petitioned Congress to buy his war photographs, Gardner presented a rival petition, claiming that he, not Brady, had originated the idea of providing the nation with a photographic history of the conflict. Congress eventually bought both collections.

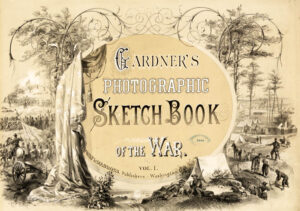

In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume work, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. Each volume contained 50 hand-mounted original prints. Not all photographs were Gardner’s; he credited the negative producer and the positive print printer. As the employer, Gardner owned the work produced. The sketchbook contained work by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, James F. Gibson, John Reekie, William Pywell, his brother James Gardner, John Wood, George N. Barnard, David Knox, and David Woodbury, among others. Unfortunately, his venture was a commercial failure as Americans were more concerned with forgetting the Civil War than looking at his views of ruined buildings, shattered bridges, and corpse-strewn battlefields. Today, this extremely rare work is hailed as a photographic masterpiece.

He was the first to compile a “rogues gallery” for the Washington D.C. police.

In 1867, Gardner was appointed the official photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad, documenting the building of the railroad in Kansas as well as the numerous Native American tribes he encountered. He closed his studio then and went West, photographing the developing frontier. Visiting Arizona and working out of Abilene and Hays, Kansas, he produced 150 construction images on the Union Pacific Railroad for the line’s use in engineering and promotion work.

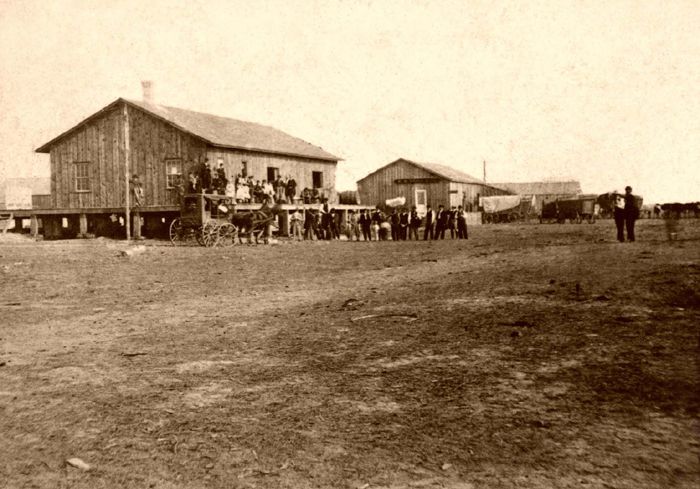

Ellsworth, Kansas Depot by Alexander Gardner, 1867.

After 1871, Gardner gave up photography and helped to found an insurance company.

In the late fall of 1882, with failing health, he died on December 10, 1882, at his home in Washington, D.C. His wife and two children survived him. He was buried in the local Glenwood Cemetery.

In 1893, photographer J. Watson Porter, who had worked for Gardner years before, tracked down hundreds of glass negatives made by Gardner that had been left in an old house in Washington where Gardner had lived. The result was a story in the Washington Post and renewed interest in Gardner’s photographs.

In the 1960s, photographic analysis suggested that Gardner had manipulated the setting of at least one of his Civil War photos by moving a soldier’s corpse and weapon into more dramatic positions. Some experts acknowledged the manipulation of photographic settings. However, in the early years of photography, the practice was not frowned upon.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, January 2024.

Also See:

Artists, Photographers, & Publishing Companies Photo Gallery

Federal Writers’ Project – Real-Life Stores

Historic Photographers of America’s History

Sources:

Ancestry.com

Battlefields

Encyclopedia Britannica

Find-a-Grave

Wikipedia