The Presidential election of 1800, also known as the Revolution of 1800, was a significant signal to the world that the newly formed United States was a country where the people determined their leaders and, thus, their fate. That’s because the vote was a contentious, nonviolent battle that led to the young country’s first and only tie for President of the United States and resulted in a transfer of power without bloodshed or violence, breaking away from the long history of violent takeovers in Europe.

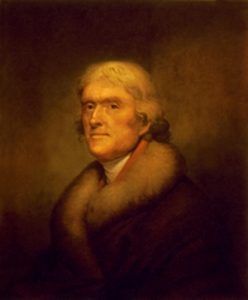

The campaign leading up to the election was bitter, full of slander and personal attacks from both sides. It pitted the Federalist Party, led by incumbent John Adams, against the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Adams’ Vice President Thomas Jefferson. It was a rematch of the election four years prior. The fact that the election of 1796 resulted in a Federalist President and a Republican Vice President was due to the way the Constitution allowed the Electoral College to vote.

But the actual tie for President in 1800 wouldn’t be between Jefferson and Adams. It would be between Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr due to that same flaw in the U.S. Constitution.

Lead up to the Election:

Federalists spread the word that the Republicans would ruin the country with their radical support of the French Revolution. At the same time, the Republicans accused the Federalists of favoring Britain, promoting aristocratic views that were destroying their values through the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Acts were four bills passed by the Federalists in 1798 in the aftermath of the French Revolution:

- The Naturalization Act amendment extended the duration of residence required for immigrants to become citizens from 5 to 14 years.

- The Alien Act, which authorized the President to deport immigrants (aliens) considered “dangerous to the peace and safety of the U.S.” (activated with a two-year expiration)

- The Alien Enemies Act, which authorized the President to apprehend and deport resident aliens if their home countries were at war with the United States (remains in-tact today)

- The Sedition Act made it a crime to publish “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” against the government or certain officials. This Act also had an expatriation the day before President Adams’ term ended on March 3, 1801.

These acts would be important in the 1800 election, as the Republicans saw Adams’ foreign policy too favorable to Britain and opposed new taxes to pay for the Quasi-War, which was an undeclared war fought mostly at sea between the U.S. and the French Republic starting in 1798, and feared that the new army called up for the conflict would oppress the people. They attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts as violations of states’ rights and the Constitution.

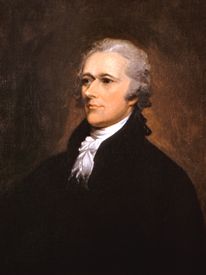

Meanwhile, Adams was also being attacked by “High Federalists” aligned with Alexander Hamilton, who thought Adams to be too moderate for the party. Hamilton even hatched a plan that would have elected Adams’ running mate Charles Pinckney as President. Still, after the Democratic-Republicans obtained and published a 54-page scathing letter against Adams by Hamilton, his efforts were damaged, as well as his and Adams’ political future. Ultimately it also hurt the Federalist Party as a whole.

The campaign saw both sides seeking any advantage, including changing the selection process of electors in several states. Republican state legislators in Georgia, for instance, replaced the popular vote with selection by the state legislature. Federalists did the same in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Meanwhile, Virginia switched from electoral districts to winner take all.

At the time, each state chose its election day between April and October. After the long-fought campaign that some thought would rip apart the country, South Carolina gathered the voting. She chose eight Republicans for the Electoral College, breaking a 65-65 national split and giving Jefferson and Burr the winning votes.

Flaw in the Constitution Exposed:

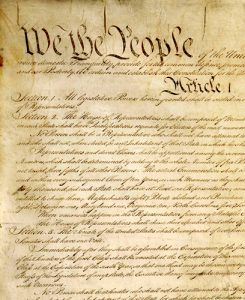

The original United States Constitution said that members of the Electoral College could only vote for President. Each elector would vote for two candidates, with the person receiving the most votes becoming President and the second most votes Vice President.

To avoid a tie in votes on the Federalist side, the party arranged for one of their electors to vote for John Jay instead of Vice President Pinckney. The Democratic-Republican’s plan was to have one of the electors abstain from casting their second ballot for Burr, but that didn’t happen. Instead, each Republican elector voted for both, resulting in Jefferson and Burr each getting 73 votes.

This put the election in the hands of the House of Representatives. Law stipulated that the outgoing House, still controlled by Federalists, would be the deciders, with each state casting one vote. New terms for both the House and President began in early March.

In February of 1801, members of the House balloted as states to determine the winner. An absolute majority vote of the 16 states was required for victory. With many outgoing Federalists unwilling to back Jefferson, most instead voted for Burr, giving Burr six of the states. The seven states controlled by Republicans gave their votes to Jefferson, with Georgia’s sole Federalist voting for him as well, giving Jefferson eight votes. But nine votes were needed, and there were two states left.

Vermont was a wash. Evenly split, the state representatives cast a blank ballot. This left things to Maryland, which had five Federalist and three Republican representatives. However, they too were split in their vote between Burr and Jefferson, resulting in another blank ballot being cast.

This went on for seven days that February, with the House casting 35 ballots and Jefferson receiving only eight of the nine states needed each time. Finally, on February 17, Federalist James Bayard of Delaware, along with his party allies in Maryland and Vermont, all cast blank ballots, resulting in both states selecting Jefferson, giving him ten states and the office of President of the United States. The final vote was Jefferson ten, Burr four, and two with no result.

Correcting the Flaw

The way the Constitution laid out the Electoral College originally stipulated each elector could cast two votes, but not for two people in the same state as the elector. The candidate with the most electoral votes became President, the second most Vice President. If there was a tie, it would go to the House of Representatives to choose the President. In the case of the Vice President, whoever received the second-highest amount of votes in the House would take office. The election of 1796 exposed the first problem with this when Federalists scattered their second votes, resulting in the Democratic-Republican presidential candidate Thomas Jefferson becoming Vice President. Many were concerned that there could be a situation where a Vice President could impede the President and even try to kill him to become President.

After the debacles in 1796, and 1800, in December of 1803, Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment (XII) to the U.S. Constitution, in which each elector must cast distinct votes for President and Vice President instead of two votes for President. This put in place measures that lessened the chance of an opposing party in the Vice Presidents’ position. It kept the clause forbidding an elector from voting for both candidates of a presidential ticket if both candidates are from the elector’s state. It also ensured that anyone ineligible to be President could not be Vice President either. The states ratified the Amendment in 1804.

The amendment did not change the composition of the Electoral College, but it did adjust the procedures for ties that go to the House. If a majority of Electoral College votes is not reached for President, the House of Representatives chooses the President. The amendment requires the House to choose from the three highest receivers of electoral votes. It also stipulates that the Senate, in the case of a tie, chooses the Vice President. That choice is limited to candidates with the two highest electoral votes. If multiple individuals are tied for second place, the Senate may consider all of them, in addition to the candidate with the highest votes. The amendment also introduced a requirement of two-thirds of the Senate to conduct the tie-breaking vote and that a majority of the Senate be required to make a choice.

The amendment further prevents deadlocks, requiring that if the House could not choose a President by March 4 (or the first day of a Presidential term in office), the candidate elected as Vice President would act as President. In 1933, the Twentieth Amendment changed the date of the beginning of the Presidential term to January 20, clarified that the Vice President-elect would only act as President if the House had not chosen a President by then, and permitted Congress to direct through legislation that would be acting President if there is neither a President-elect nor Vice President-elect by January 20.

This system of election is still in place today in the United States. Therefore it is still possible to have a Presidential candidate not reach the number of Electoral College votes needed, sending the decision for President to the House of Representatives and vice president to the Senate.

There has been one other election since the Twelfth Amendment, where the House of Representatives was the deciding body for the President of the United States. Although it wasn’t a tie, in the election of 1824 between John Quincy Adams, President John Adams son, and Andrew Jackson, neither candidate reached the majority of the electoral vote. It was also the only election where the candidate with the most electoral votes did not become President.

While not reaching a majority of the Electoral College votes, Andrew Jackson did have more votes than Adams. However, the House of Representatives chose Adams in February of 1825. Both candidates had run under the Democratic-Republican party ticket since the Federalists had dissolved in previous years, heavily damaged by the election of 1800. However, the Republican party had separated into four groups, each with its own candidate. In later years, the group led by Andrew Jackson would become the Democratic Party. In contrast, groups led by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay would become the National Republican Party, followed by the Whig Party.

Compiled and edited by Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Presidents of the United States of America

Presidential Trivia, Fun Facts and Firsts

The United States Constitution

Sources: