By Emerson Hough

Next to the fight of Wild Bill with the McCanles Gang, the fight of Buckshot Roberts at Blazer’s Mill on the Mescalero Indian Reservation is perhaps the most remarkable combat of one man against odds ever known in the West. The latter affair is little known but deserves its record.

Buckshot Roberts was one of those men who appeared on the frontier and gave little history of their past. He came West from Texas, but it is thought that he was born farther east than the Lone Star State. He had served in the United States Army, where he reached the rank of sergeant before his discharge, after which he lingered on the frontier, as did very many soldiers of that day.

He was, at one time, a member of the famous Texas Rangers and had a reputation as an Indian fighter. The Comanche had badly shot him. Again, he was on the other side, against the Rangers, and once stood off 25 of them, although nearly killed in this encounter. He was so severely crippled in his right arm from these wounds that he could not lift a rifle to his shoulder. He was usually known as “Buckshot” Roberts because of the nature of his wounds.

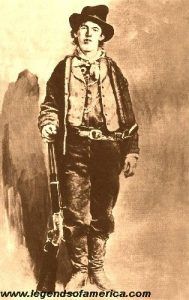

Roberts took up a little ranch in the beautiful Ruidoso Valley of central New Mexico, one of the most charming spots in the world, and all he asked was to be let alone, for he seemed able to get along and not afraid of work. When the Lincoln County War broke out, he was recognized as a friend of Major Lawrence G. Murphy, one of the local faction leaders, but when the fighting men curtly told him it was about time for him to choose his side, he curtly replied that he intended to take neither side; that he had seen fighting enough in his time, and would fight no man’s battle for him. This, for the time and place, was treason and punishable with death. Roberts’ friends told him that Billy the Kid and Dick Brewer intended to kill him and advised him to leave the country.

It is said that Roberts had closed out his affairs and was preparing to leave the country when he heard that the gang was looking for him and that he then allowed them to find him. Others say that he went up to Blazer’s Mill on April 4, 1878, to meet a friend named Kitts, who, he heard, had been shot and badly wounded. There is another rumor that he went up to Blazer’s Mill to have a personal encounter with Major Godfroy, with whom there had been some altercation. There is a further absurd story that he went to kill Billy the Kid and get the reward that was offered for him. These latter things are unlikely. The probable truth is that he, being a brave man, though entirely determined to leave the country, found it written in his creed to go up to Blazer’s Mill to see his supposedly wounded friend and also to see what was in the threats he had heard.

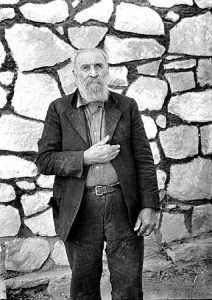

There were three eye-witnesses of what happened at that time: Frank and George Coe, ranchers on the Ruidoso today, and Johnnie Patten, a cook on the Carrizo Ranch. Patten was an ex-soldier of H Troop, Third Cavalry, mustered out at Fort Stanton in 1869. At the time of the Roberts fight, he was running the sawmill for Dr. Blazer.

Frank Coe said that he was attempting to act as a peacemaker and that he tried to get Roberts to give up his arms and not make any fight. At the peril of his life, Patten said that he had warned Roberts that Dick Brewer, Billy the Kid, and his gang intended to kill him. It is sure that when Roberts came riding upon a mule, still wet from the fording of the Tularosa River, he met there Dick Brewer, Billy the Kid, George Coe, Frank Coe, Charlie Bowdre, John Middleton, one Scroggins, and “Dirty Steve” Stevens, with others, to the number of thirteen in all. These men claimed to be a posse and were under Dick Brewer, “special constable.”

The Brewer party withdrew to the rear of the house. Frank Coe parleyed with Roberts at one side. Kate Godfroy, daughter of Major Godfroy, protested at what she knew was the purpose of Brewer and his gang. Dick Brewer told his men, “Don’t do anything to him now. Coax him up the road away.”

Roberts declined to give up his weapons to Frank Coe. He stood near the door, outside the house. Then, as it is told by Johnnie Patten, who saw it all, there suddenly came around upon him from behind the house, the gang of Billy the Kid, all gunfighters, each opening fire as he came. The gritty little man gave back not a step toward the open door. Crippled by his old wounds to not raise his rifle to his shoulder, he worked the lever from his hip.

A dozen men, the best fighting men of all that wild country, were shooting at him at a distance of not a dozen feet, yet he shot Jack Middleton through the lungs, though failing to kill him. He shot a finger off the hand of George Coe, who then left the fight. Roberts then half-stepped forward and pushed his gun against the stomach of Billy the Kid. For some reason, the piece failed to fire, and the Kid was saved by the narrowest escape he ever had.

Charlie Bowdre appeared around the corner of the house, and Roberts fired at him next. His bullet struck Bowdre in the belt and cut the belt off from him. Almost at the same time, Bowdre fired at him and shot him through the body. He did not drop but staggered back against the wall, and so he stood there, crippled of old and now wounded to death, but so fierce a human tiger that his very looks struck dismay into this gang of professional fighters. They withdrew around the house and left him there! Each claimed the credit for having shot the victim. “No,” said Charlie Bowdre, “I shot him myself. I dusted him on both sides. I saw the dust fly out on both sides of his coat, where my bullet went clean through him.” They argued, but they did not go around the house again. Roberts now staggered back into the house. He threw down his own Winchester and picked up a heavy Sharps rifle, which belonged to Dr. Appel and which he found there in Dr. Blazer’s room. Brewer told Dr. Blazer to bring Roberts out, but, like a man, Blazer refused. Roberts pulled a mattress off the bed to the floor and threw himself down upon it near an open window in the front of the house.

The gang had scattered, surrounding the house. Dick Brewer had taken refuge behind a thirty-inch sawlog near the mill, just 140 steps from the window near which this fierce little fighting man was lying, wounded to death. Brewer raised his head just above the top of the sawlog so that he could see what Roberts was doing. His eyes were barely visible above the top of the log, yet at that distance, the heavy bullet from Roberts’ buffalo gun struck him in the eye and blew off the top of his head.

Billy the Kid was now the leader of the posse. His first act was to call his men together and ride away from the spot, his whole outfit whipped by a single man! There was a corpse behind them and wounded men with them.

Thirty-six hours later, there was another corpse at Blazer’s Mill. The doctor, brought over from Fort Stanton, could do nothing for Roberts, and he died in agony. Johnnie Patten, sawyer and rough carpenter, made one big coffin, and in this, the two, Brewer and Roberts, were buried side by side. “I couldn’t make a very good coffin,” says Patten, “so I built it in the shape of a big V, with no end piece at the foot. We just put them both in together.” And, there they lie today, grim grave company. Emil Blazer, a son of Dr. Blazer, continued to live on the site of this fierce little battle, and he said that the two dead men were buried separately but side by side, Brewer to the right of Roberts. The little graveyard holds a few other graves, none with headboards or records, and the grass grows above them all.

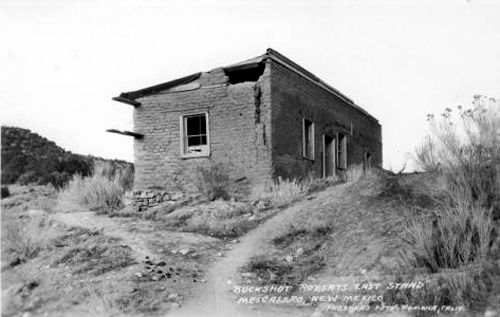

The building where Roberts stood at bay is now gone, and another adobe is erected a little farther back from the raceway that once fed the old mountain sawmill but is no longer used. The old flume still exists where the water ran over onto the wheel, and the site of the old mill, which is now also torn down, is easily traceable. When the author visited the spot in the fall of 1905, all these points were verified, and the distances were measured. It was a long shot that Roberts made and downhill. The vitality of the man who made it, his courage, and his tenacity of life and purpose against such odds make Roberts a man remembered with admiration even today in that once bloody region.

By Emerson Hough, 1907. Compiled and heavily edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Go To the Next Chapter – The Man Hunt

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw; A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Also see:

Adventures of the American West

Other Works by Emerson Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text