In the 1800s, Texas was a wild and lawless place attracting all manner of thieves, murderers, and other ruthless outlaws. To combat these many desperados and fight the Indians, who were prone to attacking the white settlers, rode the Texas Rangers, who set about taming the wild Texas frontier.

In the 1800s, Texas was a wild and lawless place attracting all manner of thieves, murderers, and other ruthless outlaws. To combat these many desperados and fight the Indians, who were prone to attacking the white settlers, rode the Texas Rangers, who set about taming the wild Texas frontier.

The Rio Grande to the south had been declared the border between the United States and Mexico; however, the Mexican government refused to recognize the boundary, insisting instead that the Nueces River was the border. This left a giant chunk of land between the two rivers, which became known as “No Man’s Land” and a prime target for outlaws.

The dispute between the two countries ultimately led the United States to go to war with Mexico in 1846 to establish the Rio Grande as the official border. However, it would take another thirty years before the Texas Rangers could rid the territory of the Mexican cattle rustlers and thieves.

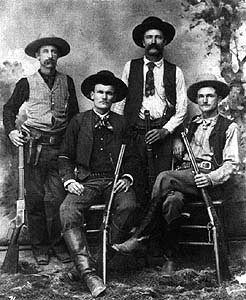

Texas Rangers, 1890.

The Texas Rangers, a roving posse of expert gunmen, were not men to be messed with. Following their adversaries everywhere, they lived out of the saddle and often dispensed justice brutally. Two of these men were Creed Taylor and William Alexander Anderson “Big Foot” Wallace, who was himself a folk hero. It was Big Foot, with Creed’s blessing, who unwittingly created El Muerto.

In 1850, a man known simply as Vidal was busy rustling cattle all over South Texas, and soon he had a high price on his head – “dead or alive.” During that summer, Vidal took advantage of a Comanche raid, which pulled most of the men northward to fight off the attack. In the meantime, the sparse settlements were temporarily left unguarded. Vidal, along with three of his henchmen, wasted no time taking advantage of the situation and gathered up many horses on the San Antonio River, heading southwest toward Mexico.

Vidal didn’t know that among the stolen herd were several prized mustangs belonging to Texas Ranger Creed Taylor, usually one of the first to defend the settlements against Indian attacks, who had not, on this occasion, gone after the Comanche. Creed’s ranch lay west of San Antonio, in the thickest of bandit territory, not far from the headwaters of the Nueces River. Due to the ranch’s location, Taylor’s livestock and horses were frequently targeted by the numerous bandits.

Taylor had had enough and quickly gathered fellow ranger Big Foot Wallace and a nearby rancher named Flores. Wallace and Taylor were as skilled as any Comanche when tracking, and the three men found Vidal’s and his henchmen’s trail.

When the three men found the outlaw camp, they waited to attack until night, when the bandits were sleeping. Catching them unaware, the thieves were killed. But just killing them was not enough. Taylor and Wallace wanted to set an example that would deter future bandits. In those days, stealing cattle and horses was a crime more serious than murder. The Rangers had tried all types of brutal justice, including stringing them up in trees and leaving them hanging, shooting them, chopping them to pieces, and leaving their bodies for animal bait. But nothing had worked to stop the outlaws.

In a dramatic example of frontier justice, Wallace beheaded Vidal and then lashed him firmly into a saddle on the back of a wild Mustang. Tying the outlaw’s hands to the pommel and securing the torso to hold him upright, Big Foot then attached Vidal’s head and sombrero to the saddle with a long strip of rawhide. He then turned the bucking horse loose to wander the Texas hills with its terrible burden on its back.

Soon, stories began to abound about the headless rider usually seen in a remote country, with its sombreroed head swinging back and forth to the rhythm of the horse’s gallop.

As time went on, more and more cowboys spotted the dark horse with its fearsome cargo, and not knowing what it was, they riddled it with bullets. But the horse and its rider rode on, and the legend of El Muerto, the headless one, began. Soon, the South Texas brush country became a place to avoid as El Muerto was credited with all kinds of evil and misfortune.

Finally, a posse of local ranchers captured the wild pony at a watering hole near the tiny community of Ben Bolt just south of Alice, Texas. Still strapped firmly on its back was the dried-up corpse of Vidal, now riddled by scores of bullet holes and Indian arrows. The body was buried in an unmarked grave near Ben Bolt, and the horse was free of its burden at last.

That should have been the end of El Muerto, but the legend would live on to this day. Soon after Vidal’s body was laid to rest, soldiers at Fort Inge (present-day Uvalde) began to see the headless rider. Travelers and ranchers in “No Man’s Land” also reported continuing to see the apparition.

In 1917, a couple traveling by covered wagon to San Diego, Texas, camped for the night outside of town. They would report the next day that as they sat by the campfire, a large gray stallion sped by with a headless man shouting, “It is mine. It is all mine.”

Another sighting of the headless wonder was reported near Freer, Texas, in 1969.

Personalized Wanted Poster at Legends’ General Store.

The legend lives on, and many still report seeing the headless rider galloping through the mesquite on clear, moonlit nights in South Texas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2025.

Also See:

Ghost Stories from the Old West

Legends, Ghosts, Myths & Mysteries

Texas Rangers – Order Out of Chaos

“Big Foot” Wallace – A Texas Folk Hero

See Sources.