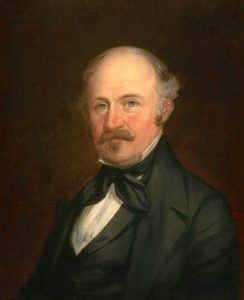

The undisputed founder of California, pioneer Johann Augustus Sutter, owned the land where gold was first discovered, beginning the famous California Gold Rush.

Sutter was born in Kandern, Germany, a few miles from the Swiss border, on February 15, 1803. He went to school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and later joined the Swiss army, eventually becoming captain of the artillery.

After military service, he worked as an apprentice in a print shop before clerking in a draper’s shop, where he met his wife, Annette D’beld. The two were married in Burgdorf on October 24, 1826, and the couple would eventually have four children. Dabbling in several businesses, Sutter was unsuccessful and decided to seek his fortune in the United States. In May 1834, he left his family, destined for New York, promising to bring them later once he was settled.

In July, he arrived in the United States and soon made his way to St. Louis, Missouri. While there, he made two trading trips to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1835 and 1836. In 1838, he traveled with a group of missionaries on the Oregon Trail to Fort Vancouver in Oregon Territory and the following year made his way to San Francisco.

California was Mexican territory at the time, and Sutter became a Mexican citizen in 1840 to obtain a land grant. In June 1841, Mexican governor Juan Bautista Alvarado granted him nearly 50,000 acres at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento Rivers. Sutter began to build a settlement on his land, which he called New Helvetia, or “New Switzerland,” with dreams of creating an agricultural utopia.

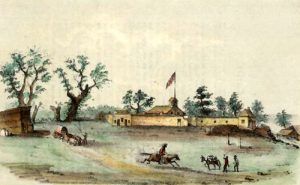

Employing members of the Miwok, Maidu, and Kanakas tribes, he began to build the settlement and, to protect it, also established Sutter’s Fort, which included 18-foot walls surrounding shops, houses, mills, and craftsmen. Completed about 1843 and strategically situated on the Oregon-California Trail and near the inland waterways from San Francisco, it soon became the primary destination for most California-bound immigrants, including the ill-fated Donner Party, whom Sutter attempted to rescue.

Sutter’s settlement rapidly grew and prospered as immigrants, trappers, and traders traveled through or settled in the area. Within just a few years, Sutter was the wealthiest and most influential man in the region, and he would later admit: “I was everything: patriarch, priest, father, and judge.” Somewhere along the line, Sutter’s family also joined him in California.

In 1847, California became part of the United States. Though Sutter first supported the establishment of an independent California Republic, when U.S. troops briefly seized control of his fort, Sutter did not resist.

Sutter’s life would change dramatically in January 1848 when one of his employees, James Marshall, discovered gold at his sawmill in what would later become the town of Coloma. Marshall immediately advised Sutter of his find, who swore all his employees to secrecy. But the “news” was just too big, and in no time, it leaked out.

As word quickly spread, some 80,000 miners flooded the area, extending up and down the length of the Sacramento Valley and overrunning Sutter’s domain. Sutter’s employees also joined the Gold Rush, and he could not protect his property. His sheep and cattle were stolen in no time, and squatters occupied his land.

As almost everything Sutter had worked for was destroyed, John deeded everything left to his son, John Augustus Sutter Jr., to avoid losing it. The younger Sutter saw the land’s commercial possibilities and promptly made plans for building a new city he named Sacramento, after the Sacramento River.

The elder Sutter deeply resented this because he had wanted the city to be named Sutterville and be built near his New Helvetia domain.

Ironically, neither John Sutter nor James Marshall ever profited from the discovery that should have made them independently wealthy. Though Marshall tried to secure his claims in the goldfields, he was unsuccessful. The sawmill where the gold was found also failed, as every able-bodied man took off searching for gold.

By 1852, John Sutter was bankrupt, and his land was filled with squatters. In 1857, the squatters took Sutter to court over the legality of his titles, and the U.S. Land Commission decided in Sutter’s favor.

However, the Supreme Court declared portions of his title invalid a year later. Sutter then sought reimbursement for his losses associated with the California Gold Rush, but received only $250 per month from the State of California in 1864. The final blow came on June 7, 1865, when a small band of men set fire to his house, destroying the structure.

Sutter and his wife, Nanette, then moved to Lititz, Pennsylvania, and John continued to fight the U.S. Government for compensation for his losses. For the next 15 years, the undisputed founder of California petitioned Congress for restitution, but little was done. On June 16, 1880, Congress again adjourned without action on a bill that would have paid Sutter $50,000. Two days later, John Augustus Sutter died in a Washington, D.C. hotel. He was returned to Lititz and is buried in the Moravian Cemetery. Mrs. Sutter died the following January and is buried with him.

In the meantime, his elder son, John Augustus Sutter Jr., who had stayed behind in California, prospered.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

James Marshall – Discovering Gold in California

Old Sacramento – Walking on History

See Sources.