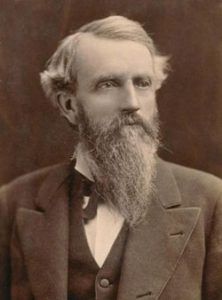

George Hearst

George Hearst was a self-made millionaire with a knack for mining that would lead to success across the American West.

Born near Sullivan, Missouri, on September 3, 1820, to William and Elizabeth Collins Hearst, George was the oldest of three children. Two years later, his sister Martha (nicknamed Patsy) was born, and later a younger brother, Philip, arrived, who was unfortunately crippled from birth. From a young age, George worked on the family farm and received minimal formal schooling.

Though Hearst was said to have had a lifelong interest in books, he had only rudimentary reading abilities. However, even without a formal education, Hearst was no dummy, as the world would soon see.

When George was 26, his father, William Hearst died owing some $10,000 to his creditors. George immediately took on the responsibility of caring for his mother, younger sister, and crippled brother.

Before long, George had improved on the farm’s profitability, opened a small store, and leased a couple of prospective lead mines. The oldest economic endeavor in Missouri, the lead had been mined in the area since 1715. Hearst had been interested in the mines since he was a child, and once he bought the lead mines, he began to study the mining business in earnest. His mines prospered, producing both lead and copper, and within two years, he was able to pay off his father’s debt.

By 1850, he had earned enough money to take care of his family and announced that he was going to California to look into gold mining. By this time, his crippled brother had passed away, and though his mother and sister opposed his decision to go west, Hearst was determined and soon organized a wagon train that included his cousins, Jacob and Joseph Clark, and headed to California in May 1850.

They finally reached Placerville in October and established a winter camp in Jackass Gulch. Placer mining throughout the winter, their results were minimal, and in the spring, they decided to move on to Grass Valley, California, where a rich lode of gold-bearing quartz had been found at Gold Hill.

Hearst soon found a rich gold-bearing quartz ledge between Grass Valley and Nevada City with much better luck. Naming his new mine Merrimac Hill after a river in Missouri, the claim was exceptionally rich, and with his former lead mining experience, Hearst quickly developed new and better ways to extract the gold. When the Merrimack hit water, it temporarily halted the mining, but the lucky Hearst had already found another rich claim he named the Potosi. By the end of the year, Hearst had used his mining proceeds to become a part-owner in the first theater in nearby Nevada City and later established a general store in Sacramento.

However, the store didn’t do so well, and after Sacramento flooded that winter, Hearst sold it in the spring of 1852 and went back to the mountains. He then sold both the Merrimac and Potosi Mines, making a considerable profit. For the next five years, he and the Clarks continued to prospect; however, as soon as they would find an ore-bearing claim, they would quickly turn around and sell it, a venture that worked over and over again. In 1857, Hearst located the extremely rich LeCompton Mine near Nevada City.

Always on the lookout for the rich finds, when word came about the rich silver finds in Nevada, Hearst went to investigate in 1859. Impressed, he sold his share of the LeCompton Mine and bought a one-sixth interest in the Ophir Mine in Washoe County. The mining camp that sprang up around the mine was called Ophir before being changed to Silver City, then Virginia City. Moving to Virginia City, he focused on separating silver and gold from the ore. In March of the following year, when the first silver was smelted from the Ophir, it touched off the “Washoe Rush” as thousands of miners flocked from California to Nevada. Soon, the entire region was referred to as the “Comstock Lode.”

It seemed that everything Hearst touched turned to gold. Though he didn’t fit the mold of a millionaire industrialist very well, there was no doubt that he was well on his way to becoming an even more powerful and successful man. Remembered as “almost illiterate” and having a taste for poker, bourbon, and tobacco, these traits didn’t hold him back. His manner and dress were often described as rough, disheveled, and crude, as he appeared in dirty and wrinkled clothes at board and miners’ meetings alike. In addition to his many mining activities, Hearst had been continuously acquiring land in the west, especially in California, and substantial ranching and livestock interests.

Phoebe Hearst

As his career peaked, Hearst received word that his mother was ill and returned to Missouri in June 1860. Spending most of his time with her until she died in early 1861, he met a young neighbor and schoolteacher named Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson. Enchanted with the 19-year-old girl, her parents were not so happy, believing that he was too old for her. However, the two eloped on June 15, 1862, and the two soon headed to California, where they lived at the Lick House in San Francisco, a famous hotel. A year later, the couple had a son on April 29, 1863 – William Randolph Hearst. As George continued to deal with his various mining interests, Phoebe remained in San Francisco.

Though Hearst had no political experience, he was nominated to the State Assembly and represented San Francisco as a Democrat in 1865. During his two years in office, he acquired the 48,000 acre Piedra Blanca Ranch at San Simeon, California. He later bought several adjoining ranches that would later become the site of the famed Hearst Castle.

Hearst Castle, California

Two years later, the prosperous Ophir Mine began to decline, and some thought that the Comstock Lode had finally been exhausted. Hearst returned to San Francisco to look after his real estate investments and began to apply his mining expertise to assessing the value of prospective mining ventures. Traveling all over the American West, he received high fees for his services and sometimes invested his money if the prospects looked bright enough. Hearst frequently invested with a man named James B. Haggin, and eventually the pair formed a mining partnership.

The first well-off mine that they partnered on was the Ontario in Utah in 1872. Though extremely expensive to develop and operate initially, it would later make them millions of dollars.

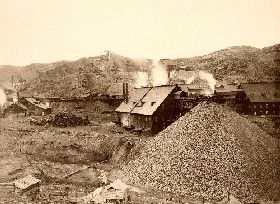

When gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1875, Hearst began to take note, and when the Manuel brothers discovered a large outcrop of gold in what would quickly become the gold camp of Lead, Hearst sent people to investigate. In 1877, Hearst himself arrived in Deadwood and, along with Haggin, bought the mine from the Manuel brothers and named it the Homestake Mine. Buying up additional claims in the Deadwood area, the Homestake Mining Operation soon was the largest in the Black Hills and the leading producer of gold in the United States.

Hearst continued to invest in other mines, including the San Luis Mine in Mexico that proved to be highly profitable.

In 1878 Hearst began developing the Piedra Blanca Ranch in southern California, which he had purchased in 1865. His son, William, would later develop the site into the palatial retreat known as San Simeon.

In 1880, George acquired the small San Francisco Examiner as repayment for a gambling debt. Though he had little interest in the publishing business, he kept it because he felt the Democratic Party needed a friendly newspaper in San Francisco.

Though he tried to make it profitable, he was unsuccessful until his son volunteered to take it over. Though George tried hard to get William interested in mining, his son was more interested in the journalism business, and in 1887 he gave him control. Just three years later, William had built up the newspaper to a value of a million dollars. The Examiner would later become the foundation of the Hearst Publishing Empire.

In the meantime, Hearst was still avidly pursuing his mining interest. In 1881, Marcus Daly contacted Hearst, asking his help in developing a silver mine that he had located on Anaconda Hill near Butte, Montana. Trusting Daly explicitly, Hearst bought a quarter interest in the Anaconda without even seeing it. Though its opportunity appeared to be silver and gold, the Anaconda wound up being developed into one of the world’s largest and most profitable copper mines.

The following year, Hearst’s name was submitted for the Governor of California. Though he lost the election, his political days were not yet over. In 1885, he ran for Senator, but again he lost. However, in early 1886, when Senator John F. Miller died in office, Hearst was appointed to fill the vacancy. The popular vote elected Hearst to the Senate in November 1886, and for the next six years, he and Phoebe lived in Washington D.C.

While still in office, Hearst died in Washington D.C. on February 28, 1891. He is buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California. His wife, Phoebe, and his son, William Randolph Hearst, were also buried there later.

In 1899, a publication produced by the University of California described Hearst like this:

“There are no differing thoughts among his friends, who were numbered by thousands from the humblest to the highest, as to the intrinsic worth of Senator Hearst’s character. In private and in public life, he was a man of scrupulous integrity. He was a faithful friend. He was without pretense or presumption of any kind. His home, whether the rude shanty in the mining camp, on Sutter’s Fork, or the Yuba, or that modern Pactolus, Feather River, or in a mansion on the hills of San Francisco, or an elegant residence in the national capital, that home, however humble or palatial, was the emblem of hospitality, and “welcome” was the password.

Mr. Hearst was a man of strong common sense. He was simple, genial, companionable. He had a lively vein of humor. He was hopeful and courageous. His heart was kindly, forgiving, humane. He was an excellent judge of character, readily detecting the true from the counterfeit. In physique, he was tall and striking in appearance. His energy, thrift and success, his integrity, manliness, and unostentation, mark him out as a representative American.”

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Comstock Lode – Creating Nevada History

Rough & Tumble Deadwood, South Dakota

HBO’s Deadwood -Fact & Fiction

Silver Mining in the United States