From Cheely-Raban Syndicate, 1922

Sudden riches often lead to madness, say old prospectors. The mere idea that he has acquired a vast fortune often unsettles a man’s mind. Also, tragedy in some dreadful form often stalks at the elbow of those searchers for wealth in the hills whose picks have tapped deposits of extraordinary richness. One of the most striking instances of this kind — but only one of hundreds — was the story of Horace Tabor of Denver, Colorado, who became immensely wealthy overnight from a gold strike in the Leadville district. He bought a seat in the United States Senate and spent money like water. He built a magnificent theater in Denver, which he called the Tabor-Grand, under whose name it was until recently operated. On the night of the opening, it is related, Tabor was entering the theater to the private box that had been prepared for him. He had with him a gay company of men and women.

Suddenly his arm was seized by a witch-like old woman, who clung to him while she cursed him shrilly for leaving his wife — the woman who had helped him bear the burdens of poverty — when he became wealthy. “Look there,” shrieked the hag, pointing to the splendid curtain before the stage, on which was painted the ruin of an ancient temple, with the motto beneath:

“So pass the works of men; Back to the Earth again. Ancient and Holy Things Fade like a dream.”

“Back to the earth again,” she shrilled. “A year from today, you will be dead — in a pauper’s grave.”

Her prophecy was a true one. Tabor lost his wealth nearly as fast as he made it and died in poverty and misery within a year.

Later, the American Zinc Company took over the great Silver Dyke property at Neihart, Montana, a deposit of silver ore 200 feet in width. From it, they expected to make significant profits. But, the two men who prospected the mine and bonded it were inmates of the state insane asylum at Warm Springs. They were Dick Heidenreich and Peter Erickson, old-timers in the Neihart district.

A well-grounded superstition among miners is that ill-luck or violent death is the legacy of all discoverers of hidden treasures. The original locators of some 35 or 40 of the richest mines in the west were known to have come to tragic ends.

On Jul. 1, 1864, “Uncle Johnny” Cowan, Reginald Stanley, D. J. Miller, and D. J. Crab were returning to Virginia City, Montana, after a discouraging prospecting trip in the Big Belt mountains when they came upon a gulch that gave promise of containing placer gold. They decided to make their last cast of fortune’s dice there and sank a shaft in the creek bed, which they named Last Chance. They struck colors, and gold to the value of $20,000,000 was mined there in four years. Three of the four members of the party died paupers. Stanley lived to old age and ended his days in comfort in England.

Bill Fairweather, discoverer of Alder Gulch, Montana, in May 1863, whose pick tapped a stream that yielded $100,000,000 in gold, lies in an unmarked grave at Virginia City, Montana, within a few miles of where he and five companions drove their discovery stakes. Only one of the six had any money left at the end. This was Tom Cover, one of the original owners of the townsite of Riverside, California.

In Sunset Hill cemetery, on a hill overlooking the city of Bozeman, Montana, a plain marble slab bears the following inscription:

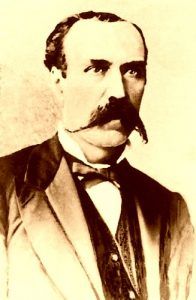

“In memory of Henry T. P. Comstock, discoverer of the famous Comstock Lode. Storey Co., Nevada. Died at Bozeman Sept. 27, 1870. Aged 50 years.”

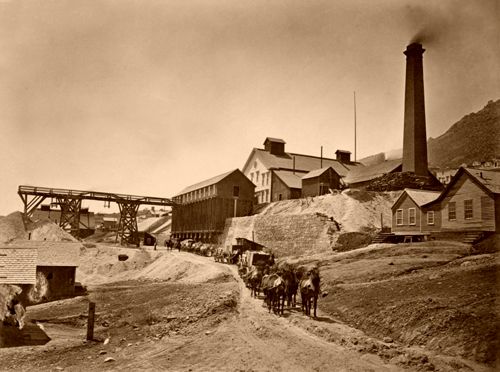

Beneath this piece of marble lies all that is mortal of the body of one of those adventurers of the early western gold strikes who discovered vast streams of golden wealth in mountain gulches and who usually died in squalor, victims of the lurid life of the mining camps. On the date given on the slab of marble perished by his own hand, friendless and penniless, the man whose name is borne by the richest gold and silver-bearing lode the world has ever known — the famous Comstock Lode of Virginia City, Nevada, which produced more than $350,000,000 for its owners, and which was immortalized by Mark Twain in his story, “Roughing It.”

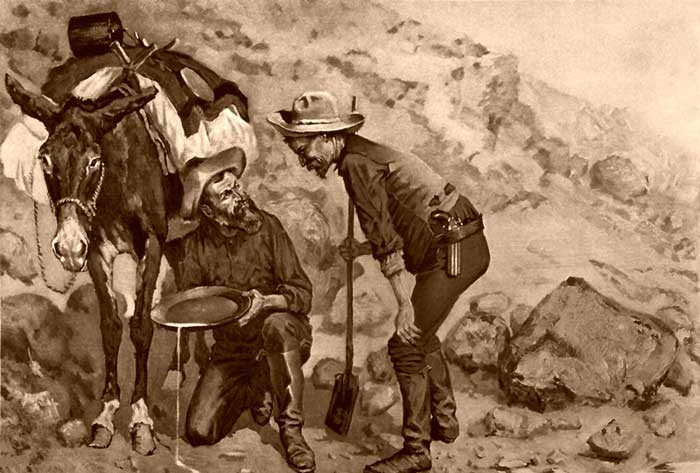

The story of the discovery of the Comstock Lode begins with the coming to Nevada of two brothers, Hosea and Allen Grosh, sons of a Pennsylvania Universalist minister, who struck rich silver ore on a portion of what afterward was called Comstock Lode about 1855 or 1856, and realized that they had made an important discovery. However, they had no capital for quartz mining and were forced to spend most of their time placer mining for gold to buy food while neglecting the rich quartz deposits.

There is a story to the effect that a rich stockman and trader by the name of Brown had agreed to supply them with funds to develop their silver mine, but just after he had sold his store and was about to join them, he was murdered by road agents. Then Hosea Grosh pierced his foot with the point of his heavy pick and a month later died in their rude cabin from blood poisoning.

Allen Grosh, heart-sick over the death of his brother and discouraged by repeated misfortunes, at length, decided to cross the Sierra mountains to California to raise money with which to develop the silver property, which he had proved by prospecting, to be far bigger in size and richer than he and his brother had at first thought. But, he fell victim to what was called by old-timers the curse of the Comstock, and after being overcome in a mountain storm, he managed to drag himself to a mining camp and died there from the results of exposure 12 days later.

When Allen Grosh started on his fatal journey, he cast about for someone to leave in charge of his effects. The most available man seemed to be the placer miner, Henry Comstock, working on a nearby creek. It is said that a contract was drawn up, by the terms of which Comstock was to have one-fourth interest in one claim for keeping the property from being “jumped” in the absence of Grosh. Comstock agreed to live in the little stone cabin built on the Grosh brothers’ claim. However, Allen Grosh, a well-educated man and a thoroughly equipped prospector did not take Comstock into his confidence or tell him anything of what he called his “monster vein.” Instead, Grosh hid his assaying equipment and the memoranda of his discovery before Comstock came to the cabin, and long after his death, when his heirs searched for months to find evidence to bear out their claims to this rich mining property in court, little could be found.

There were so many claims made about what really happened the following spring after Allen Grosh’s death in the winter of 1856 that it is almost impossible to get at the true facts. The story generally accepted was not the one told by Comstock but concerns two Irish prospectors who were down on their luck — Peter O’Riley and Pat McLaughlin — who had taken up an unpromising appearing claim for placer mining not far from the Grosh discovery claim. Getting little by placer mining, they decided to dig a trench straight up the hill from the small stream to cut through some hard, blue clay and yellowish gravel they had noticed on the hillside.

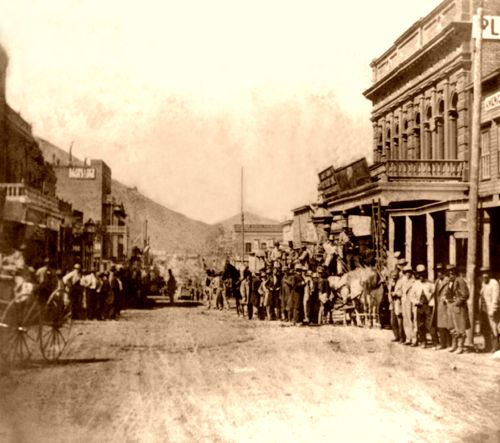

At a depth of four feet, they came upon a deposit of dark, heavy soil sparkling with minute flakes of gold. Running for a gold pan, one of them tested the dirt. The pan contained many dollars’ worth of gold. They had discovered the top of the famous Ophir claim, the northern end of the vast Comstock Lode. Just as they were finishing the last cleanup, up rode Henry Comstock. He had been looking for a lost horse and now galloped down the ridge in time to see the prospectors looking at the gold in the pan and yelling with joy. Comstock shouted: “You’ve struck it, boys — but you’re on my land.”

Comstock, it is believed, had no claim of any sort to the ground, but he apparently was a foxy individual and had done some quick thinking. “Look here,” he said to the two Irishmen as he swung off his horse, “this spring where you’re getting your water for placer mining was old man Caldwell’s. You know that, for there’s his sluice box. Manny Penrod and I bought his claim last winter, and we sold a one-tenth interest to Old Virginia the other day. You two fellows must let Penrod and me in on equal shares with you if you’re going to do any mining here.”

The two prospectors had to agree.

Now occurred the first “freeze-out” the district had known. Comstock jumped on his horse and loped off swiftly to the little camp nearby, called Gold Hill, and found the character he had mentioned by the name of Old Virginia. This man was a drunken prospector and barroom loafer. Comstock quickly explained the situation to him and offered his horse and part of a bottle of whiskey for a bill of sale to Old Virginia’s alleged interest in the ground. After a few drinks, the old man agreed and signed a bill of sale that Comstock wrote out.

Comstock later told a story about the matter that was an artistic piece of lying. In his account of the strike, he said, “I had owned the greater part of Gold Hill and had given the prospectors working there their claims. O’Riley and McLaughlin were working for me at Ophir, and when they struck the gold, I caved in the cut and went ahead to organize my company. I then opened the Comstock Lode.”

The little drama, as it really was played, was very simple. Comstock, one of the most ignorant and bombastic of men, managed by loud talk and pure “gall” to make himself the most important personage in the camp when the extent of the strike began to be realized. He never had, in truth, found anything, but he claimed everything in sight. In a few weeks, when miners came from all points, the big man of the new bonanza appeared to be Comstock.

Comstock was wildly avaricious when mining and as wildly extravagant with his gold when it was obtained. He bought whatever his fancy dictated and gave it away the next moment. His only pleasure seemed to be spending money like water; most of his companions were like him in that respect.

McLaughlin sold his interest in the ground for $3,500. O’Riley was more fortunate and hung on till he secured $40,000, but he spent it all in stock speculation and died in an insane asylum. McLaughlin hung around the district and drank himself to death, being buried at public expense.

Two months after the ledge was struck, Comstock sold his holdings for $11,000. After spending most of this in riotous living, he went north and prospected in Idaho, later drifting into Montana, where he died by his own hand.

Initially published in 1922 by the Cheely-Raban Syndicate. Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

About This Article: This article was published in 1922 as a chapter in the book Back-trailing on the Old Frontiers, published by the Cheely-Raban Syndicate of Great Falls, Montana. The book was the first in a three-volume series that published a number of stories illustrated by Charles M. Russell, which had appeared in Sunday editions of daily newspapers in all parts of the United States. The article is not verbatim as it has been slightly edited for grammatical corrections.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West

Comstock Lode – Creating Nevada History