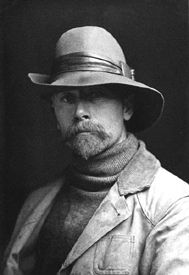

Edward S. Curtis, 1898

Edward Sheriff Curtis was a photographer of the American West, who was most well known for his photographs of Native Americans in the early 20th century.

Born near Whitewater, Wisconsin, on February 16, 1868, to Reverend Johnson Asahel Curtis and Ellen Sheriff Curtis, the family moved to Minnesota around 1874. Curtis dropped out of school in the sixth grade and soon built his own camera. In 1880 the family lived in Cordova Township, Minnesota, where his father worked as a retail grocer. At the age of 17, Edward became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Two years later, in 1887, the family moved to Seattle, Washington, where Edward purchased a new camera and investing $150 into an existing photographic studio with Rasmus Rothi, he became a 50% partner. This endeavor was short-lived, and after only six months, Curtis left Rothi and formed a new partnership with a man named Thomas Guptill in a studio called Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photo engravers.

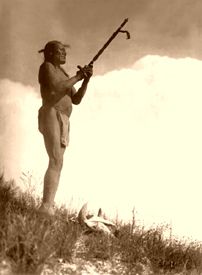

In 1892 Edward married Clara J. Phillips, and the couple would eventually have four children. In the bustling frontier city of Seattle, his photography business began to thrive. In 1895, he met and photographed Duwamish Princess Angeline, who was known by her tribe as Kickisomlo, the daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. This was to be his first portrait of a Native American. His favorite subjects beyond the studio’s confines were Mount Rainier, city scenes, and, increasingly, local Indians. He was also quick to follow the news, reporting on the hardships which befell the prospectors who joined the gold rush to the Klondike in 1897.

George Bird Grinnell, 1890

In 1898 while photographing Mt. Rainier, Curtis came upon a small group of scientists, one of whom was George Bird Grinnell, an expert on Native Americans. Both Grinnell and Curtis were invited to go along on the famous Harriman Alaska Expedition in 1899, in which Curtis was designated as the official photographer. Afterward, Grinnell invited Curtis to join an expedition to photograph the Blackfeet Indians in Montana in 1900.

During the expedition, Curtis witnessed the Sun Dance ceremonies, rituals of pain willingly suffered “for strength and visions.” Through this experience together with Grinnell’s tutelage, Curtis came to his developing conception of a comprehensive written and photographic record of the most important Indian peoples west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers who still, as he later put it, retained “to a considerable degree their primitive customs and traditions.” Though he initially agreed with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs that Indians could not survive unless they forfeited their traditional lifeways and adapted to a new culture, over time, he grew to respond to the government’s policy towards Indians with fierce anger.

In 1906 J.P. Morgan offered Curtis $75,000 to produce a series on North American Indians. The series was to be in 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs, with Morgan to receive 25 sets of the series and 500 original prints. During the work, Curtis took over 40,000 photographs from over 80 tribes. When completed, 222 sets were published, which not only held photographs; but also documentation on Native American traditional life, biographical sketches, tribal lore and history, and descriptions of traditional foods, housing, garments, recreation, ceremonies, and funeral customs. In some cases, his documentation is the only recorded history. Edward’s goal was to document the way of life before it disappeared, writing in the introduction to his first volume in 1907: “The information that is to be gathered… respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.”

He also made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Indian language and music. The series was issued in limited editions from 1907-1930.

In October 1916, Edward’s wife Clara filed for divorce and three years later was granted Curtis’ photographic studio and all of his original camera negatives as her part of the settlement. However, Curtis wouldn’t stand for it and went to the studio with his daughter, Beth, and destroyed all of his original glass negatives rather than have them become her property. However, she went on to manage the studio with her sister.

Around 1922 Curtis moved to Los Angeles, California with his daughter Beth, and opened a new photo studio. However, it wasn’t an immediate success, and he also worked as an assistant cameraman for famous Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille. He also worked as an uncredited assistant cameraman in the 1923 filming of The Ten Commandments.

On October 16, 1924, Curtis sold the rights to his ethnographic motion picture In the Land of the Head-Hunters to the American Museum of Natural History. He was paid $1,500 for the master print and the original camera negative. Unfortunately, it had cost him over $20,000 to film the production.

In 1927, he was arrested for failure to pay alimony over the preceding seven years. The total owed was $4,500, but, for whatever reasons, the charges were dropped. In 1928, desperate for cash, Curtis sold his project’s rights with J.P. Morgan to Morgan’s son. In 1930, he published the final volume of The North American Indian.

In 1935, the Morgan estate sold the rights and remaining unpublished material of the series to the Charles E. Lauriat Company in Boston for $1,000 plus a percentage of any future royalties. The sale included 19 complete bound sets of The North American Indian, thousands of individual paper prints, the copper printing plates, the unbound printed pages, and the original glass-plate negatives. Lauriat bound the remaining loose printed pages and sold them with the completed sets. The remaining material remained untouched in the Lauriat basement in Boston until it was rediscovered in 1972.

After his long and large project of The North American Indian had finally been completed, Curtis’ health was much broken by the strain of incessant travel compounded by legal and financial worries. He took some interest in the remnant of his studio in Los Angeles, which had long been run by his daughter. He also dabbled in mining, farmed a small-holding in Whittier, and wrote but, didn’t publish much memoir material, and in his later years watched his life’s work seemingly slide into oblivion.

On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a heart attack in Whittier, California, in the home of his daughter, Beth. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, California. An obituary that appeared in The New York Times stated:

“Edward S. Curtis, an internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Bess Magnuson. His age was 84. Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, J. Pierpont Morgan. The forward for the monumental set of Curtis books was written by President Theodore Roosevelt. Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.”

Though his life’s work, The North American Indian, never proved popular during his lifetime, as its editions were expensively produced and issued over such a long period, he would be happy to know that modern history has much appreciated the value of the project. Exhibitions have been mounted, anthologies of pictures have been published, and The North American Indian has been increasingly cited in others’ research. There has also been a reprint edition of the entire work.

©Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated December 2020.

Also See:

Artist, Photographer, & Publisher Photo Galleries