By Hiram Martin Chittenden in 1902

Alexander Harvey was among the boldest men and most reckless desperadoes known to the fur trade. He was well built physically, about six feet tall, and weighed between 160-170 pounds. He was firmly knit, capable of great endurance, and wholly devoid of physical fear in ordinary interactions when not under the influence of liquor or passion; he was disposed to be fair and reasonable. But, he had a perverse and unruly temper, and once it was aroused, he was relentless and unforgiving.

Harvey was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a young man, was apprenticed to learn the saddler’s trade. However, his headstrong disposition got him into trouble with his employers before long, and he left them. He joined the American Fur Company in 1831 and was posted on the upper Missouri River. He was with Prince Alexander Maximilian as they explored the area in 1833.

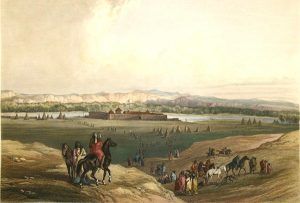

He was sent to Fort McKenzie, Montana, the most remote of the company’s posts. Here he remained for several years, but his wicked and intolerant demeanor toward his associates made his presence a constant source of irritation. Word was then sent to St. Louis, Missouri, that he would have to be gotten rid of somehow. Mr. Chouteau sent him his discharge and requested him to report in person at St. Louis to ensure his early departure.

It was Christmas before the discharge arrived, and at that season of the year, it was considered almost madness to undertake a long journey, mainly alone. But Harvey, despite all his complaints and opposition (no doubt feigned in large part,) made ready to start the following day on the long journey of nearly 2,500 miles through a desolate and dangerous country. “I will not let Mr. Chouteau wait long on me,” he said. “I shall start in the morning; all I want for my journey is my rifle and my dog to carry my bedding.” He reached St. Louis early in March, and Mr. Chouteau was so impressed with the hazard of the performance that he renewed Harvey’s engagement.

It was about time for the annual steamboat to start up the river, and Harvey made ready to return at once. On his way up, he remarked to Charles Larpenteur, also returning to Fort Union, North Dakota, from St. Louis, that he had several settlements with the gentlemen who had caused him his long winter’s tramp. “I never forget or forgive,” he said; “it may not be for years, but they will all have to catch it.” Accordingly, he kept his eye out for those he suspected of complicity in the movement against him. He found one at Fort Clark, North Dakota, and gave him an unmerciful pounding, remarking when he was through, “That’s number one.” At Fort Union, he found several more, and as fast as he could single them out from the rest of the men of the fort, he would knock them down and administer a terrible beating.

Harvey kept on in the company’s employ and served them well, but he had aroused the hatred of most of the other employees, and there was no doubt many plots to take his life. In 1841 he was sent down from Fort Union, North Dakota, to Pierre, South Dakota, with mackinaw boats laden with furs. He was to return on the spring steamboat from St. Louis. To assist him on the down voyage was a Spanish man named Isidoro, a bitter personal enemy of Harvey. Some believed this singular action of the authorities at Fort Union to signify a plot to murder Harvey on the way. The trip, however, passed off all right, and the two men returned with the boat to Fort Union.

Soon after their return Isodoro opened up hostilities in earnest and started to parade around with his rifle, threatening to kill Harvey. The latter, thinking he was drunk, kept out of his way, and the day passed without further development. The next day, Alexander Culbertson ordered all the clerks to go to the warehouse and make up the equipment for Fort McKenzie, Montana. Going there in a little while himself, Culbertson found that Isodoro had not put in an appearance as directed. He and Harvey then went into the retail store, where they found the Spaniard standing behind the counter. Harvey asked him what he meant by his conduct the day before and challenged him to come out. The Spaniard did not stir, and Harvey then went back into the store and said, “You won’t fight me like a man, so take that!’ and shot him through the head. After this, he went into the middle of the fort, saying, “I, Alexander Harvey, have killed the Spaniard. If there are any of his friends that want to take it up, let them come on.” But no one dared to do so, and this was the last of the Spaniard.

A few years later, in 1843, Harvey was the principal culprit in a diabolical tragedy at Fort McKenzie, Montana. The trader in charge of the post was Francois A. Chardon, almost as desperate a character as Harvey himself. Through one of those chance misunderstandings which now and then occurred, a couple of Blackfeet Indians killed a black servant working at the post. It happened that Chardon thought a good deal of the fellow, and in his exasperation, he resolved on a terrible revenge. He laid the matter before Harvey, and the latter gladly agreed to carry out the details of Chardon’s plan. This was to have the cannon of the bastion trained upon the fort’s door when the next Blackfeet band came in to trade. Two or three of the chiefs would then be admitted, and while the door was crowded with Indians, the cannon would be discharged, and the three chiefs massacred. Though not as many were killed as Harvey had hoped, three died, and three were wounded.

This was not the only atrocious deed by Alexander Harvey at Fort McKenzie. On another occasion, when a party of five Indians undertook to steal some cattle belonging to the post, Harvey started pursuing them. He soon overtook one Indian who had shot a cow and, firing at him, broke his thigh. The Indian fell to the ground and lay there when Harvey came up and sat down beside him. The heartless Harvey then lit a pipe and made the poor Indian smoke, saying, “I am going to kill you, but I will give you a little time to take a good look at your country.” The Indian begged for his life, saying, “Comrade, it is true I was a fool. I killed your cow, but now you have broken my thigh; this ought to make us even — spare my life!’ “No,” said Harvey; “look well, for the last time, at all those nice hills — at all those paths which lead to the fort, where you came with your parents to trade, playing with your sweethearts — look at that, will you, for the last time.” So saying, with his gun pointed at his victim’s head, he pulled the trigger, and the Indian was no more.

Harvey eventually became a very heavy burden to the American Fur Company. Although an able man and a good trader, his outrageous deeds were too much for his associates to endure. There was a strong undercurrent of feeling against him, which was liable to result in his murder. Harvey began to see that his life was in danger and was probably ready to relinquish the service as soon as he could decently do so.

The matter came to a head in 1845 when an abortive attempt to murder him ended in his severance of further connection with the company. Harvey was in temporary charge of Fort Chardon, which had been built at the mouth of the Judith River after the abandonment of Fort McKenzie. Albert Culbertson went up with the spring outfit from Fort Union to take charge and build a new post farther up. Malcolm Clark, James Lee, and an interpreter named Jacob Berger were along. These three men were enemies of Harvey and concerted together to kill him.

When Harvey heard of the boat’s approach, he rode some 20 miles downstream to meet it. Leaving his horse with a man who had come with him, he went to the boat and entered the cabin. He offered to shake hands with Clark, but the latter replied that he would have nothing to do with such a man and struck him over the head with a tomahawk. Berger also struck him with a rifle. Harvey grappled with Clark and would have thrown him into the river had Lee not disabled him with a blow from his pistol across the hand. Harvey then escaped to shore, took his horse, and fled to the fort.

The employees took sides with him, placing the fort in a state of defense and refusing admission to any of the boat party. Finally, after much hard pleading, Culbertson was admitted. He had always been friendly to Harvey and now agreed to give him a draft for all his wages and a letter of recommendation on the condition that Harvey would surrender the fort. Harvey then left the fort in a canoe with one man.

After stopping for two days at Fort Union, he pursued his course down the river. Before leaving, he said, “Never mind! You will see old Harvey here again.” Harvey then reported the illegal sale of liquor by traders on the upper Missouri River. Afterward, he joined up with Robert Campbell and others in organizing the Missouri Fur Company in opposition to the American Fur Company. He was next working at Fort Campbell, Montana. He must have married sometime in his last years, as in a letter written to Campbell on July 17, 1854; he asked him to care for his daughters. He died just a few days later, on July 20, 1854, and was buried at Fort Pierre, South Dakota.

By Hiram Martin Chittenden, 1902. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

About the Author: This article was written by Hiram Martin Chittenden and included in his book, The American Fur trade of the Far West, published in 1902. Chittenden served in the Corps of Engineers, eventually reaching the rank of Brigadier General. He was responsible for many notable projects, including work at the Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks and the Lake Washington Canal Project. He was also an author, penning historical volumes, tour guides, and poetry. As it appears here, the story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for the clarity and ease of the modern reader.

Also See:

List of Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men

Trading Posts and Their Stories